I’ve just returned from Guantanamo, where my clients and a majority of the other 166 men there have been on hunger strike for over two months. Most of them have been cleared for release or will never be charged. But the Obama administration has refused to send them home.

I met with men who are weak and have lost between 30 and 40 pounds. They told me of other men who are skeletal and barely moving, who have coughed up blood, passed out, and one who tried to hang himself.

One of the men I met with, Sabry Mohammed, a Yemeni who remains detained years after he was approved for release by the Obama administration, said, “We are dying a slow death here.” Yet the authorities say they will not let men die–they will force-feed them when their body weight drops dangerously low, strapping them into chairs and forcing a tube up their noses that pumps formula into their stomachs. The military reports that so far, 11 men are being “saved” this way. Yet as one of the men put it, the irony is that “the government will keep us alive by force-feeding us but they will let us die by detaining us forever.”

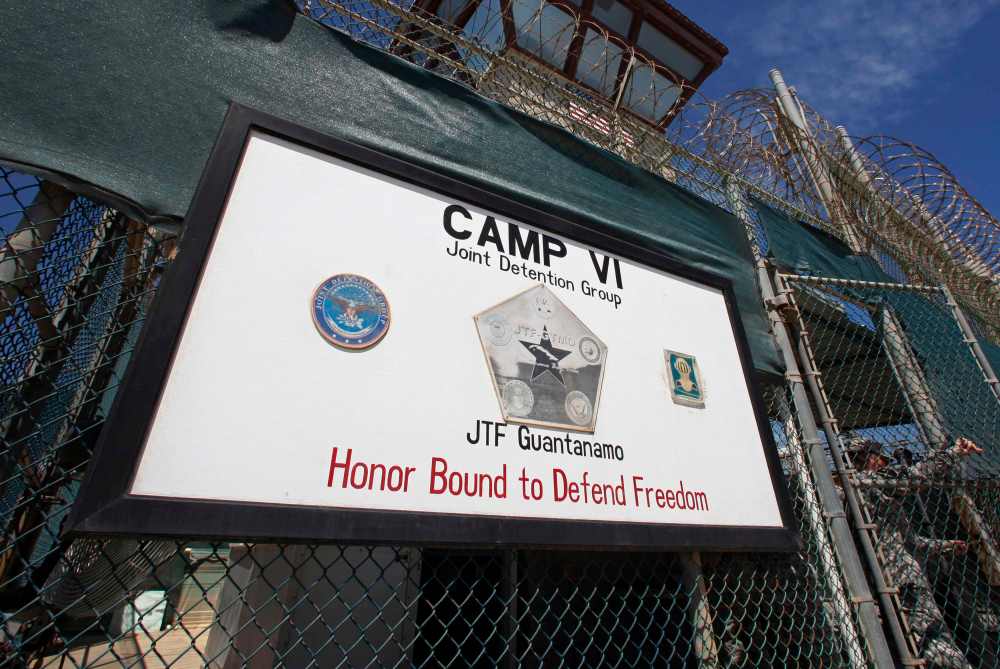

Today, 166 men remain at Guantanamo, more than eleven years after they arrived in hoods and shackles. Most are being held without charge and will never be charged. The Obama administration has approved more than half of the men–86–for transfer, but hasn’t mustered the political will to overcome congressional hurdles, despite saying it can and will. As their indefinite detention stretches into a second decade, men are aging, declining and dying. Last September, Adnan Latif, a husband and a father, a man twice cleared for transfer under the Bush and Obama administrations, was the ninth prisoner to die. The current crisis at the base had specific triggers, but there has been an emergency at Guantanamo for years.

The strike was sparked in early February, when prison authorities ordered searches of the men’s Qurans. One man told me, “I won’t even touch the Quran without washing my hands, how could I use it to hide something dirty?” The men viewed the searches as desecration, which should hardly have been news to those in charge. A former Muslim chaplain at Guantanamo once described the handling of the holy books as “the most contentious issue” at the prison. Given the sensitivity of the practice and the history of religious abuse at Guantanamo–acts like throwing Qurans on the ground and shaving detainees’ beards as punishment–the authorities should have known better. Indeed, former commanders did know better. In a 2009 review of conditions at Guantanamo, ordered by the Obama administration, a commander at the base recognized that standard operating procedures “do not permit searching of the Koran.” The rule reflected an “elevated respect” for detainees’ religious concerns–a lesson learned from the early years. It is unclear why that changed. Another of my clients said, “They are taking the camp back to 2006.”