Author and sports historian Dr. Louis Moore, a professor at Grand Valley State University, knows that one thing Black athletes have never done is simply “stick to sports.”

His forthcoming book, “The Great Black Hope,” is dropping in September and covers the history of the Black quarterback. And his previous two books investigate similar intersections of race and athletics: the first, called “We Will Win the Day,” focuses on the legacy of activist athletes, while the other, “I Fight for a Living,” uses boxing to chronicle the “battle for Black manhood” starting in the late 19th century.

We chatted about the decadeslong effort to silence Black athletes, the obstacles activist athletes face today, and how Black sports journalists have altered American life through their work. Check out the video below! I’ve transcribed some highlights from our interview below, as well (edited throughout for clarity and length).

JJ: You’ve written extensively about the Black quarterback, and we saw Patrick Mahomes succeed yet again in the Super Bowl. What was your takeaway?

LM: The game was just amazing because of Patrick Mahomes. If you think about the historical view of the Black quarterback, he’s not supposed to have that kind of patience, not supposed to have that kind of confidence in himself. And when you watch Mahomes, he has all of that. That’s the reason why they won. Mahomes is just cool and steady. And you hope that GMs looking around the league for their new quarterback realize that [about Black QBs]. There was a time that they didn’t. But you combine the game with the halftime show — Usher — and you get this moment of Black excellence. You start with “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” You have Patrick Mahomes, you have Usher — it was really the perfect Sunday.

JJ: A few years ago, we were having this conversation about people boycotting the NFL over athletes’ outspoken demonstrations against racism. That tension seems to have faded away. Has the NFL successfully papered over the activism that people like Colin Kaepernick brought to the forefront?

LM: Yes and no. Look, there’s a reason why he’s blacklisted from the league. It was to send a message to everybody else: “Don’t be like him — get in line.” And I think the players understood that. But the “no” comes in that part of playing that means you do have a platform. So while Kaep is being blacklisted from the league, you do have the players union talking about cash bail. And the NFL allows players to put stuff on their helmet. That’s small, but it can be personal. C.J. Stroud, the next up-and-coming Black quarterback, is having conversations about jail reform. His dad’s in prison, and now he can be the voice of that. So the NFL silenced Kaep. It might have silenced protest during the national anthem. But there’s still room for players to do what they want to do because the NFL needs them.

JJ: Where does the history of the activist athlete begin?

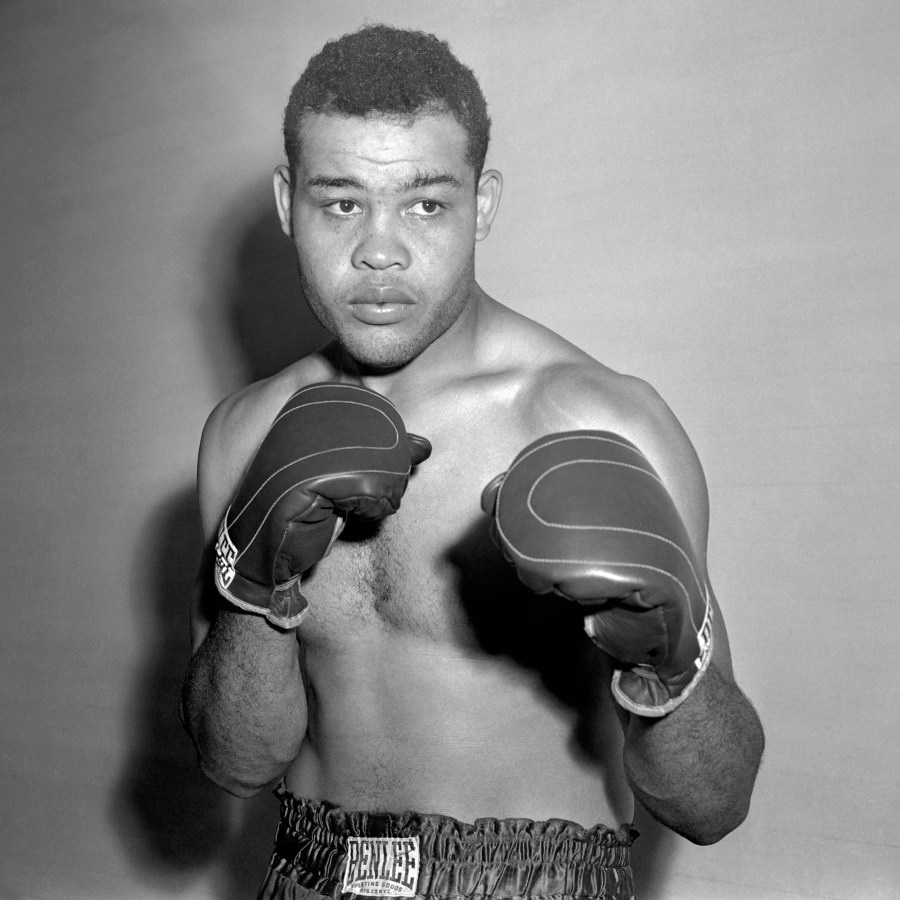

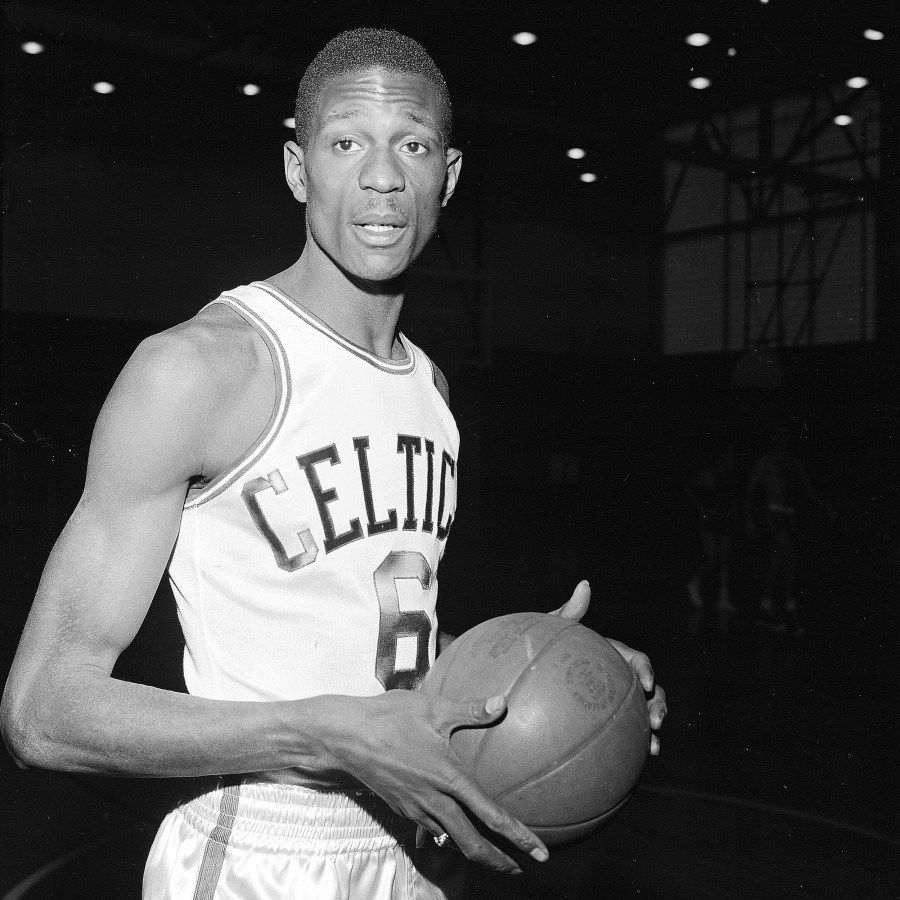

LM: I like to point to two main athletes. One is [boxer] Joe Louis. At the height of his career, when he’s still the heavyweight champion of the world, he’s publicly talking about being anti-Jim Crow. He’s out there during the 1948 presidential election trying to get Black folks to register and to vote. He’s using his voice to talk about stuff like the poll tax and poverty. The other athlete at that time is Jackie Robinson. Jackie during his career went after Jim Crow. He spent time after his career writing presidents, telling presidents like Eisenhower to do something about lynching, writing Nixon and going after JFK. And you also had guys like Bill Russell doing the same thing: boycotting a game, going to Mississippi, fighting for integration and education.

JJ: I appreciate you mention those two people in particular, because they’re vaunted figures now. But their activism wasn’t appreciated then as it is today.

LM: A lot of folks hated Jackie Robinson in real time. It’s that whole “shut up and dribble, shut up and play” idea. And Jackie felt that. People in baseball didn’t like him, people in America didn’t like him. And Jackie never backed down. You can find articles in the late 1960s where he’s talking about seeing the American flag and what that represents to him. An American flag bumper sticker on the car — that was off-putting to him because of everything that’d gone on in the past and was currently going on. He famously talked about not standing for the national anthem. That’s Jackie Robinson in real time — people didn’t like him. People hated Muhammad Ali, too. Now, 50 years later, everybody will tell you how much they loved him. But at the time Ali suffered a lot of hate and a lot of venom toward him.

JJ: Which current athletes embody the spirit of the activist athlete that you’ve celebrated in your work?

LM: An easy one is LeBron James. He doesn’t get a lot of credit, but what he’s doing for education reform in Akron and making sure kids get a chance to go to college is huge. So was using his name for that “More than a Vote” campaign to make sure that people have an opportunity to register and vote. Another one I think we’ve forgotten over the last four years is Renee Montgomery, who was in the WNBA, who was also part of “More than a Vote.” She was an integral part of that #VoteWarnock movement in 2020.