On Tuesday, former Trump Organization CFO Allen Weisselberg began his testimony with what some considered a blockbuster admission: Under a severance agreement signed shortly after he left the company, he is entitled to $2 million, paid in eight equal installments.

As of now, the Trump Organization hasn’t even paid him half of that amount, according to the agreement’s payment schedule — and he must fully comply with the agreement to be paid in full.

While prosecutors used the agreement to attempt to show that Weisselberg remains entangled with Trump and financially motivated to please him, their brief discussion of Weisselberg’s severance agreement — which has now been admitted into evidence and is part of the trial record — only skimmed the surface of that agreement. Read as a whole, the agreement requires much from Weisselberg, and given the history between the parties, which includes convictions on multiple felony tax fraud counts for both Weisselberg and the Trump Organization last year, certain provisions seem sketchy, at best.

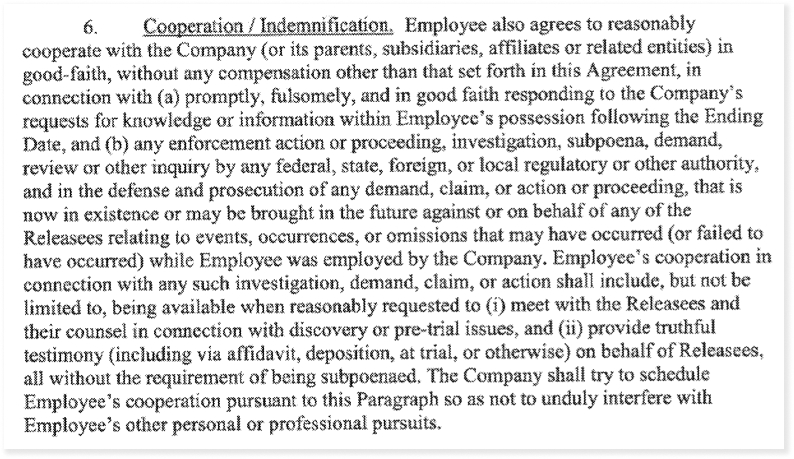

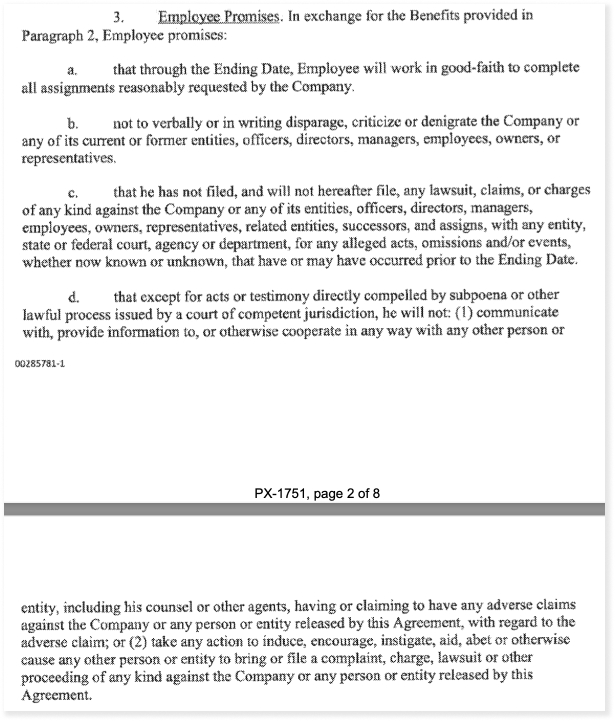

To be clear, I’m not faulting the Trump Organization or Weisselberg for including a non-disparagement clause, which obligates Weisselberg not to bad mouth the company or its people, or even for requiring Weisselberg to cooperate with the company in any litigation or investigation that relates to his employment there. Those provisions are relatively standard in severance or settlement agreements.

But even language that’s not entirely atypical can take on a different gloss when the parties are Trump and his company, on one hand, and Weisselberg, on the other.

The best example appears in Paragraph 3(d), which reflects Weisselberg’s promise to not talk to or otherwise help those who might have claims or lawsuits against the Trump Organization and its executives, former and current, among others.

Specifically, that provision states that:

except for acts or testimony directly compelled by subpoena or other lawful process issued by a court of competent jurisdiction, he will not (1) communicate with, provide information to, or otherwise cooperate in any way with any other person or entity, including his counsel or other agents, having or claiming to have any adverse claims against the Company or any person or entity released by this Agreement, with regard to the adverse claim; or (2) take any action to induce, encourage, instigate, aid, abet or otherwise cause any other person or entity to bring or file a complaint, charge, lawsuit or other proceeding of any kind against the Company or any person or entity released by this Agreement.

And while the agreement makes clear that Weisselberg is not precluded from “filing a charge or complaint with or participating in any investigation or proceeding conducted by, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), or a comparable state or local agency,” there is no carve out for his voluntarily speaking to or supplying information, even through his counsel, to, say, any prosecutorial entity, like the Manhattan district attorney’s office or any unit of the federal Justice Department, or any tax or finance enforcement agency, including the IRS, the Securities and Exchange Commission, or New York’s Department of Financial Services.