It has been a week since a barely 18-year-old killed 21 people in the second deadliest school shooting in U.S. history. Last week, media and elected officials swarmed Uvalde, Texas, a small, tight-knit and predominantly Latino community where every resident, from a deputy sheriff to newspaper writers, seems to have lost someone they love. And yesterday, funeral services began with mass for one of his victims, veteran teacher Irma Garcia, and her husband, Joe, who died of a heart attack two days later.

Uvalde, its residents say, is a tiny town where wild chickens roam the streets; by contrast, I live in America’s biggest city, where rats rule the subways. Still, the reaction to Uvalde felt universal, even in these most polarized of times: Who amongst us was not nauseated and sleepless?

Like families all across America, I mourned the teachers and students of Robb Elementary, whose everyday joys mirrored those of my own family. When I heard that 11-year-old Layla Salazar loved to listen to “Sweet Child of Mine” with her dad on their way to school, I wept; my older daughter sings that and other rock anthems with my husband each morning. Like parents from coast to coast, I hugged my daughters too tight in the mornings and waited anxiously for them to come home hours later. Yet as stories of children’s resourcefulness and trauma unfolded and the timeline of law enforcement intervention shifted, I kept thinking about the Supreme Court.

In fact, I haven’t stopped thinking about the court since a shooter, allegedly steeped in white supremacy and antisemitism, killed 10 Black Americans at a Buffalo supermarket earlier this month. And it’s because of a looming gun case that, as Amy Davidson Sorkin wrote in The New Yorker recently, may make our nation’s gun violence epidemic worse.

If the case poised to overturn Roe v. Wade is the court’s expected summer blockbuster, its sleeper hit is expected to increase access to guns at perhaps the worst time: when active shooter incidents are up dramatically; school shootings have reached an all-time high; and recent polling shows “huge support” for a variety of gun restrictions. Specifically, before June’s end (and potentially the same week that it topples Roe), the court could invalidate a New York law restricting the concealed carrying of handguns on the ground that it violates the Second Amendment.

That law is nothing new; it’s literally been on New York’s books for more than a century (and well before any women won the right to vote). What’s changed is the court itself. In the 14 years since Justice Antonin Scalia’s self-described “legacy opinion,” District of Columbia v. Heller, held the Second Amendment protects individuals’ rights to own guns for self-defense, the court’s center collapsed; three devoted, young conservatives joined its ranks; and other, veteran conservatives have moved out from Scalia’s shadow to map their imagined America onto their purported originalism.

And that’s how this Court agreed to hear a challenge to New York’s 111-year-old law. The case was brought by two residents of Rensselaer County, where “153,000 people [are] spread over 955 square miles,” as their lawyer explained. Even Rensselaer County’s biggest city has under 50,000 residents and lies more than 150 miles from New York City. The residents, Robert Nash and Brandon Koch, are not exactly deprived of gun rights. The men do have licenses to carry concealed handguns outside their homes for hunting and target practice and self-defense in areas not “frequented by the general public;” one of their licenses also allows him to carry concealed for self-defense while traveling to and from work. Both, however, were denied unrestricted licenses to carry concealed because, neither of them established “proper cause,” or “a non-speculative need for armed self-defense in all public places.”

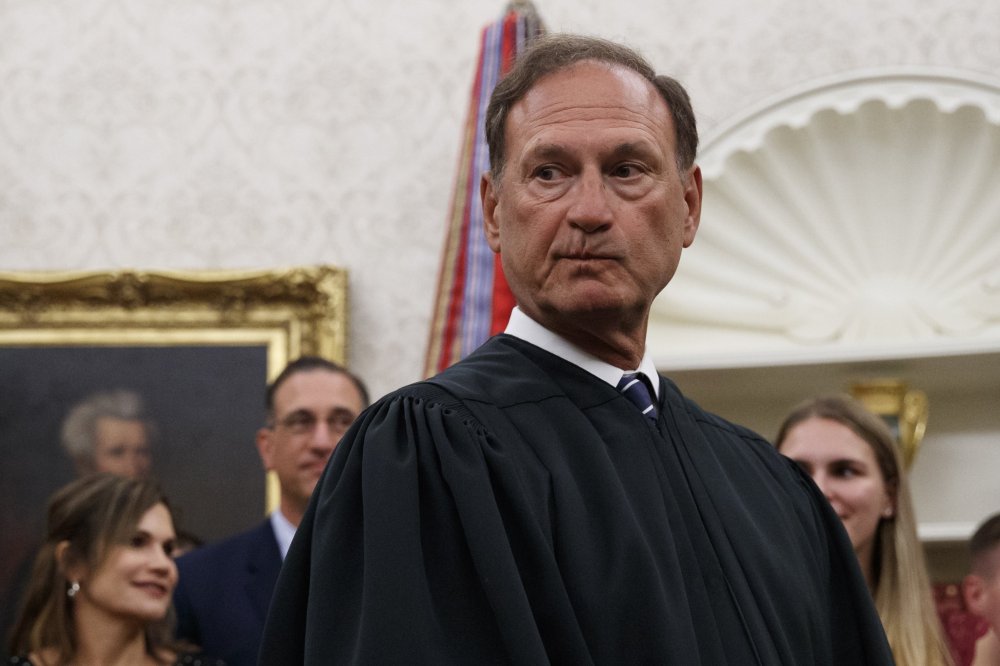

Yet despite their distance from New York City, all Justice Alito could talk about at oral argument was urban danger—and “ordinary” Americans’ fear. For all his fixation with “history and tradition” in undoing Roe, Alito leapt back to the future of present-day New York in the name of gun rights. Unlike Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, both Big Apple natives, Alito apparently has not lived or worked in New York. Rather, as we learned during his 2006 confirmation process, he was raised in Trenton, New Jersey, graduated from Princeton and then Yale Law School, and then began his public service career, first in the Department of Justice and then as a federal judge in his home state. Still, insisting that Manhattan’s “ordinary, hard-working, [and] law-abiding” workers are clamoring to carry concealed handguns, Alito asked New York’s lawyer:

So I want you to think about people like this, people who work late at night in Manhattan, it might be somebody who cleans offices, it might be a doorman at an apartment, it might be a nurse or an orderly, it might be somebody who washes dishes. None of these people has a criminal record. They’re all law-abiding citizens. They get off work around midnight, maybe even after midnight. They have to commute home by subway, maybe by bus. When they arrive at the subway station or the bus stop, they have to walk some distance through a high-crime area, and they apply for a license, and they say: Look, nobody has told — has said I am going to mug you next Thursday. However, there have been a lot of muggings in this area, and I am scared to death. They do not get licenses, is that right? . . . . How is that consistent with the core right to self-defense, which is protected by the Second Amendment?

That lawyer sounded stunned. The answer to rising gun violence, she suggested, especially in public transit, isn’t removing limits on gun licenses. Indeed, “the idea of proliferating arms on the subway is precisely, I think, what terrifies a great many people …[P]roliferating guns in a populated area where there is law enforcement jeopardizes law enforcement because when they come, they now can’t tell who’s shooting, and the … shooting proliferates and accelerates.”

Moreover, Alito deploys a sympathetic group of beleaguered, blue-collar workers — janitors, doormen, nurses and dishwashers — to highlight the Second Amendment’s “core right to self-defense.” Putting aside the Court’s own acknowledged limits on that right, which he elides, and its fairly recent expansion, which he ignores, his imagined late-night commuting dilemma is almost comic. In the wake of multiple mass shootings, including one on a New York City subway, it is instead chilling.