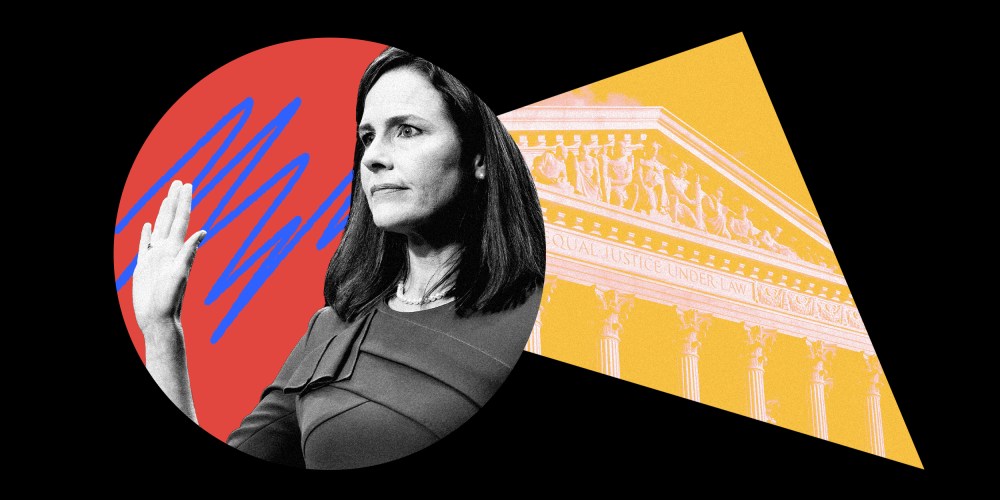

Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., a former prosecutor, opened the committee’s impromptu law school seminar Tuesday with a softball question for Judge Amy Coney Barrett, asking her to define in “real English” just what she and her mentor — the late Justice Antonin Scalia — mean when they refer to “originalism” and “textualism.”

From this morning: Judge Amy Coney Barrett gives the definitions of “originalism” and “textualism” in Sen. Graham’s impromptu Originalism 101 seminar pic.twitter.com/eMzT7qDNsm

— Hayes Brown (@HayesBrown) October 14, 2020

To the casual observer, Barrett and Scalia have the imprimatur of history on their side. It follows that if you want to determine how and whether laws fit within the framework of the Constitution, you should just … read it? The words are right there. Why leave it up to judges operating in today’s world who seem poised to consign history to the recycling bin?

But that thinking falls apart when you begin to probe it. I’d go as far as to say it’s really the so-called originalists who are overwriting history with their focus on, as Scalia put it, “original meaning.”

Rather than as a “living document,” Scalia saw the Constitution as “dead, dead, dead.” Barrett in her answers so far this week shows that she shares that view. But the narrowness of how they actually apply that idea becomes apparent when you consider the fundamental constitutional shift that occurred after the passage of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, as New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie pointed out on Twitter.

given that the constitution was effectively rewritten by the reconstruction amendments, it would be great to see a supreme court nominee say something like “I will interpret the Constitution as it was understood in 1870.”

— b-boy boooo-eebaisse (@jbouie) October 13, 2020

Through this revamping of the Constitution — and through later revisions, like the 19th and 24th amendments — the ideas of the founders themselves have already been superseded in the text. What makes the authors of the first 10 amendments more valid than people like Republican Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, whose contributions in the Reconstruction era delivered broader rights to more people?

When pressed about this through the course of the day, Barrett turned to what’s been called the Ginsburg rule — to not comment on cases that might come before her once she is confirmed and seated, or really any case she hadn’t written about directly. That might be less of a concern if it hadn’t led to her missing what should have been layups for someone who agrees with the text as written, as opposed to someone who can twist legal history to their whims under the guise of following the founders’ intent.

Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar’s question asking Barrett whether intimidation at the polls is illegal went viral — since, you know, it is — but Barrett’s lead-up was honestly more telling. Given the chance to cite the 15th Amendment’s exceedingly clear language granting Congress the power to protect voting rights, Barrett equivocated, saying she didn’t write Shelby v. Holder, a 2013 decision that neutered a key part of the Voting Rights Act.

Since Barrett cited the Ginsburg rule, it’s worth noting that the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was one of the most effusive nominees when it came to answering senators’ questions. At least when it came to what’s called settled law, provisions of the law deemed to be so established that challenging them would be almost unthinkable. Part of the way laws become settled is through the review of precedents over time, like those set down in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education or, say, 1973’s Roe v. Wade.