Norfolk State University, a historically Black college in Virginia, announced this week that former NFL quarterback Michael Vick will be the Spartans’ next head football coach. That means that 15 years after he was released from federal prison for his involvement in a dogfighting ring and nine years after he played his last NFL game, Vick is writing the next chapter in what has become one of the greatest redemption arcs in American sports this century.

Vick is writing the next chapter in what has become one of the greatest redemption arcs in American sports this century.

Not everyone is on board, of course. The president of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals had something negative to say about Vick. He’ll never be forgiven by some people. Still, Norfolk State and Vick seem to need each other. And there may be no one more qualified to teach players how to move forward after making disastrous unforced errors.

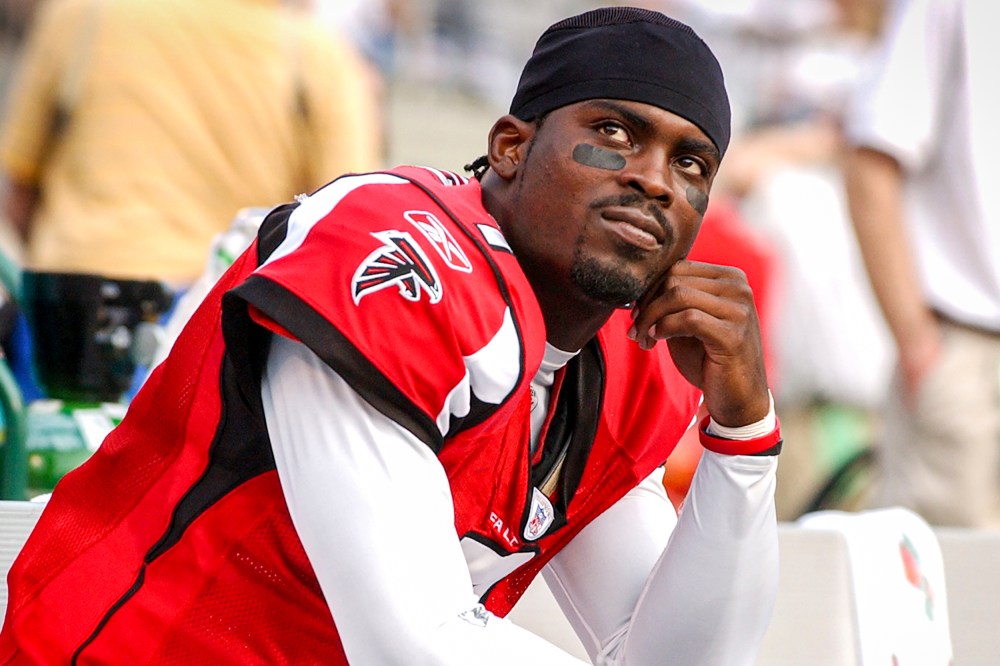

In his prime, Vick was a gift to football. As a quarterback, he possessed the speed of a track star, the evasiveness of an elite running back and a cannon for an arm. When the Falcons drafted him from Virginia Tech in 2001, Vick became the first Black quarterback to be taken with the top overall pick in an NFL draft. And he turned the Atlanta Falcons, a perennial NFL also-ran, into a team everybody wanted to watch. In 2006, he became the first quarterback to rush for 1,000 yards in a season, a feat that wouldn’t be repeated until Lamar Jackson did it 13 years later. The 10-year, $138 million contract the Falcons gave him in 2004, was, at that point, the largest contract any NFL player had ever signed.

At the same time, Vick was making a series of awful choices that made it apparent that he didn’t fully appreciate how good he had it. In 2007, when he was 27 and at or near the peak of his athletic ability, he pleaded guilty to his involvement in a dogfighting ring near his hometown of Newport News. That ring also included suspected drug dealers who were under federal investigation.

About Michael Vick and the constantly renewed virtual signaling:What seems to get lost is that actually he put in the work regarding reform.He spoken numerous times in the community about his transgressions, stayed away from the folks he was involved with, and worked with the humane society.

— Evan F. Moore (@evanfmoore.bsky.social) 2024-12-19T18:37:08.757Z

The details of what went on at Bad Newz Kennels — including the brutal executions of dogs that didn’t make the cut to fight competitively — were the main source of anger at Vick, but there was also anger that someone whose athletic ability was unrivaled and who had earned so much money and fame threw it away. The black-and-red #7 Falcons jersey gave way to a federal inmate number at prisons in Virginia and Kansas where he served a total of 21 months.

When Vick got out of prison, he played first for the Philadelphia Eagles, then the New York Jets and the Pittsburgh Steelers. Though his game was never the same as it had been with the Falcons, his off-field turnaround had already begun. He sought mentorship and received it from Tony Dungy, the first Black NFL head coach to win a Super Bowl and a notably religious man. Vick, who had been notoriously private, even with teammates, started to come out of his shell. He wrote and spoke publicly about his mistakes. He expressed contrition for his crimes and even gratitude for his growth behind bars. He spoke out against dogfighting even as animal rights protesters showed up at football stadiums to jeer him.

For some people, that anger doesn’t appear to have dimmed. In a statement to Fox News this week, PETA President Ingrid Newkirk called Vick a “charming, charismatic psychopath,” but she noted that at least she doesn’t believe he’ll fight dogs anymore.