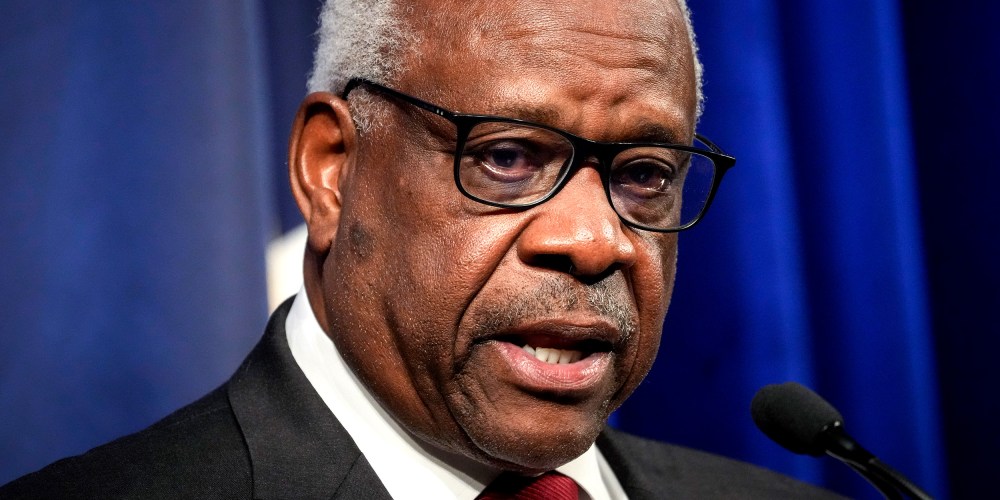

In a concurring opinion to Friday’s Supreme Court ruling overturning Roe v. Wade, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote, “In future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell.” The rulings Thomas referred to guarantee the right to contraception, same-sex relationships and same-sex marriages.

Justice Clarence Thomas, a Black man, is married to Ginni Thomas, who’s white.

But those substantive due process precedents also include Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court’s 1967 decision that says that laws banning interracial marriage violate the equal protection and due process clauses of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. And Justice Clarence Thomas, a Black man, is married to Virginia “Ginni” Thomas, who is white.

Unlike Thomas, the other justices, both conservative and liberal, contended with what Friday’s decision could mean for cases that include Loving, and seven mentioned Loving by name.

But the only African American on the Supreme Court, and the only Supreme Court justice in an interracial marriage, doesn’t mention Loving at all. Though Thomas argues that all those other precedents should be reconsidered, he implies by his silence that the one that affects him personally is sacrosanct.

He doesn’t acknowledge that his decision and the decision of his conservative colleagues could theoretically give his own state of Virginia, which had to be forced by a Supreme Court ruling to permit interracial marriages, another shot at banning them.

I’m not the only one who believes Loving seems intentionally left out.

Attorney Gloria J. Browne-Marshall, author of “She Took Justice: The Black Woman, Law, and Power – 1619 to 1969,” told me Friday, “Clarence Thomas is in an interracial relationship that would not be supported under the legal theory he espoused today.” Not mentioning Loving, Browne-Marshall said, “makes him a hypocrite. … The word ‘marriage’ is not in the Constitution. If he believes in states’ rights, he’d also believe in states’ right to say a Black man cannot marry a white woman.”

The other conservative justices, all of who are white and married to other white people of the opposite sex, apparently found it necessary to describe, either explicitly or implicitly, Loving v. Virginia as a decision they believed was safe.

“None of the other decisions cited by Roe and Casey involved the critical moral question posed by abortion,” Justice Samuel Alito wrote in the majority opinion. “They are therefore inapposite. They do not support the right to obtain an abortion, and by the same token, our conclusion that the Constitution does not confer such a right does not undermine them in any way.” Alito argued that abortion was different because it dealt with “potential life.”

In his concurring opinion, Justice Brett Kavanaugh mentions Loving by name: “First is the question of how this decision will affect other precedents involving issues such as contraception and marriage —in particular, the decisions in Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 (1965); Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U. S. 438 (1972); Loving v. Virginia, 388 U. S. 1 (1967); and Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U. S. 644 (2015),” he wrote. “I emphasize what the Court today states: Overruling Roe does not mean the over- ruling of those precedents and does not threaten or cast doubt on those precedents.”

But the three liberal justices, retiring Justice Stephen Breyer, and Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, argue that Friday’s decision does indeed cast such doubt.

The majority that says those precedents are safe has got to know that future justices won’t be bound to anything this court says.

“The law offered no protection to the woman’s choice in the 19th century. But here is the rub. The law also did not then (and would not for ages) protect a wealth of other things,” they wrote. “It did not protect the rights recognized in Lawrence and Obergefell to same-sex intimacy and marriage. It did not protect the right recognized in Loving to marry across racial lines. It did not protect the right recognized in Griswold to contraceptive use. … So if the majority is right in its legal analysis, all those decisions were wrong, and all those matters properly belong to the States too — whatever the particular state interests involved.”