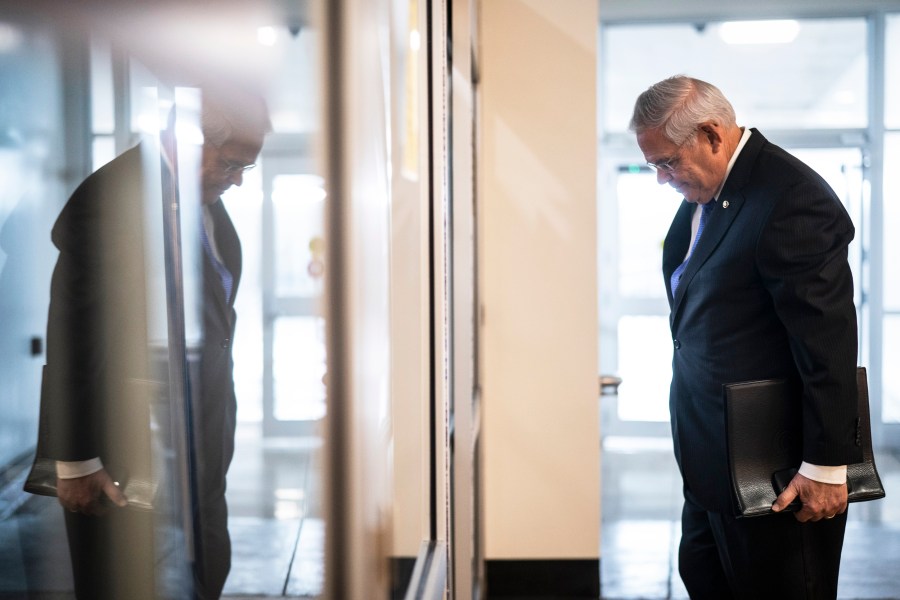

It was a bit of déjà vu Friday when a federal indictment against Sen. Bob Menendez, D-N.J., was made public. Menendez, a three-term senator and the chair of the powerful Foreign Relations Committee, and his wife, Nadine, stand accused of having accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars in the form of “cash, gold bars, payments toward a home mortgage, compensation for a low-or-no-show job, a luxury vehicle and other items of value,” according to the indictment. In return, they’re alleged to have helped three New Jersey businessmen get rich and aided the Egyptian government in the process.

This isn’t the first time Menendez has been indicted on accusations of corruption, and the latest federal investigation has been public knowledge since October. (He and his wife have denied all wrongdoing in respective statements.) But that Menendez was charged at all this time is something of a minor miracle, considering a 2016 Supreme Court ruling that raised the bar for what counts as corruption for elected officials. If the allegations in Friday’s indictment are true, though, Menendez managed to clear that bar in a feat of extreme disregard for his role as a public servant.

That Menendez was charged at all this time is something of a minor miracle.

Menendez was last charged in 2015 on eight bribery counts alleging he accepted lavish gifts, vacations and campaign donations from a Florida ophthalmologist in exchange for political favors. When the case went to trial in 2017, federal prosecutors said Menendez had “sold his office for a lifestyle he couldn’t afford.” But Menendez had a stroke of good fortune in the interim: McDonnell vs. U.S.

Bob McDonnell, a former Republican governor of Virginia, and his wife, Maureen, had been convicted in 2014 on charges of bribery and corruption for having taken $175,000 in loans and gifts from a businessman who’d hoped to get help promoting studies of a nutritional supplement. But then the Supreme Court unanimously determined that it wasn’t enough for an official to merely get nice things to qualify as corruption; those things had to be directly connected to an “official act” from an elected official. “Setting up a meeting, hosting an event, or calling an official (or agreeing to do so) merely to talk about a research study or to gather additional information” wasn’t enough to cross that ethical threshold, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote.

McDonnell was spared a two-year prison sentence thanks to that ruling. He wasn’t the only one to feel the effects of the decision as lower courts began to apply this new standard. Most infamous was Democratic former Rep. William Jefferson of Louisiana, who was caught with tens of thousands of dollars hidden in his freezer; most of his corruption charges were tossed on appeal in 2017. And Menendez most likely benefited from the laxer definition of corruption, given that his case ended in a mistrial in 2018. A federal judge acquitted him on several charges before the Justice Department could retry him, leading the Justice Department to drop the case altogether.

In hindsight, the Supreme Court decision seems a bit self-serving when you consider the ethical issues we’ve seen from its ranks. Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito in particular have been showered with gifts, trips and other perks from the very right-wing figures who have business before the court. But Alito and Thomas have shrugged off any calls for them to recuse themselves from further cases, let alone resign, as they claim there’s nothing to show that those favors have directly affected their decision-making. (That argument has become harder to swallow in light of Thomas’ latest reported ties to the Koch Network’s funders and his subsequent change of heart about an important judicial doctrine.)