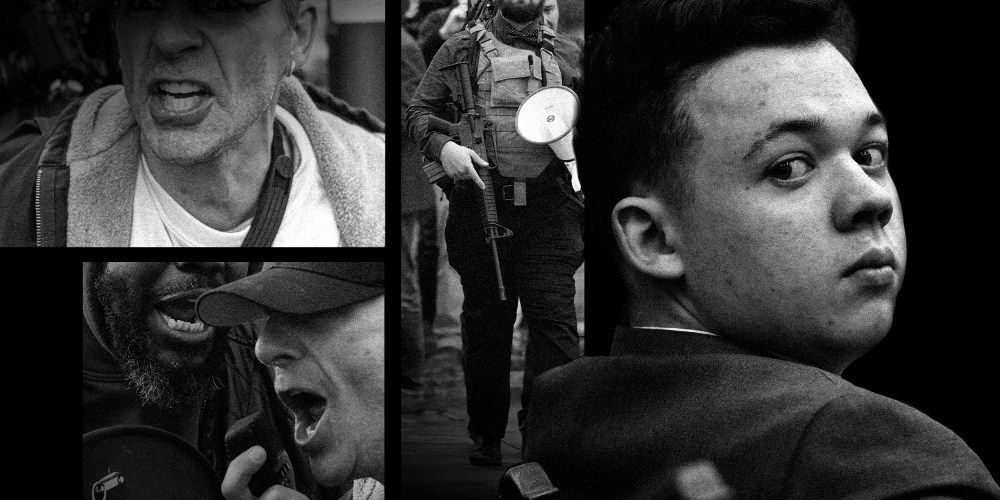

Kyle Rittenhouse, a teenager who fatally shot two men and injured another at an antiracist protest last year in Kenosha, Wisconsin, was acquitted on all charges on Friday afternoon. He had been charged with homicide, attempted homicide and recklessly endangering safety, and could’ve faced a life sentence if convicted.

For many the verdict is an outrage and a brazen miscarriage of justice. Rittenhouse is a Blue Lives Matter enthusiast who went to protests against a police shooting with a military-style rifle that he obtained illegally, falsely told people he was a medic, and ended up killing and hurting people who felt threatened by him. The overwhelmingly white jury appears to have given Rittenhouse the benefit of the doubt, after a trial in which the judge at times appeared to show favorable treatment of the defendant, and in a country in which it’s almost impossible to imagine a Black defendant accused of similar crimes receiving such easy treatment.

In other words, the Rittenhouse verdict easily reads like a referendum on the nation’s ongoing clashes over the state of racism in American life: not just an expression of mercy toward Rittenhouse, but white vigilantism.

The whole situation would never have emerged anywhere but in a deeply ill society.

But I think that’s probably not the best way to look at it. Instead, this case was both smaller and bigger: It was decided based on a narrow question of self-defense under a permissive law, not Rittenhouse’s ideological predilections. At the same time, Rittenhouse’s series of encounters was only possible in a society with truly harrowing social maladies, including a pathological obsession with guns and a rising culture of right-wing militias. Did Rittenhouse set out to shoot people that night? That question is unanswerable. But the whole situation would never have emerged anywhere but in a deeply ill society.

Here are three takeaways from this trial — and the national conversation surrounding it.

1. Rittenhouse’s case was about self-defense. And it was hard to argue against.

While our national conversation among liberals often centered on the Rittenhouse trial as a matter of racial justice, the crux of the legal battle was whether the prosecution could prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Rittenhouse did not act in self-defense when he fired his shots, according to Barbara McQuade, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School and former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan.

As she explained in a column for MSNBC prior to the verdict, that that was a very high bar to meet under Wisconsin’s vaguely worded law:

Under that law [Wisconsin’s law of self-defense], deadly force is permitted if a defendant “reasonably believed that the force used was necessary to prevent imminent death or great bodily harm to himself.” Reasonableness is to be viewed based on “the defendant’s position under the circumstances that existed at the time of the alleged offense.” Generally, someone who provokes an attack is unable to use self-defense, but Wisconsin law is a little more generous, even contradictory. It provides that a “person who engages in unlawful conduct of a type likely to provoke others to attack, and who does provoke an attack, is not allowed to use or threaten force in self-defense against that attack.” That prohibition would seem to apply to Rittenhouse, whose alleged illegal possession of a semi-automatic rifle provoked others to attack him. [After McQuade wrote this, the judge dismissed the illegal possession of a firearm charge since under Wisconsin law 17-year-olds are allowed to possess long-barreled guns.] Even then, however, the law says a defendant may still use deadly force if he reasonably believes he has no other means to avoid death or great bodily harm. What the law taketh away, it giveth back. In this case, Rittenhouse can argue that even if he provoked others to attack him by openly carrying his semi-automatic rifle at a mob scene, he was still able to use deadly force under Wisconsin law because he reasonably believed he had no other alternatives at those moments to avoid death or great bodily harm.

What this means is that the jury wasn’t rendering a judgment on whether Rittenhouse should’ve brought a gun with him to Kenosha, whether he had good politics, what precedent his behavior could set, or whether it was appropriate to cosplay a paramedic or a police officer. It was deciding whether at the very moments that he used deadly force could he argue that it was reasonable to believe he was in serious danger of bodily harm or death. And on this front, Rittenhouse — no matter what you think of him as a moral or political actor in a general sense — had a pretty strong case.

Rittenhouse first used deadly force against Joseph Rosenbaum. Rosenbaum — who witnesses said had threatened to kill Rittenhouse — chased Rittenhouse into a parking lot, threw a bag of toiletries at him, and was shot when Rittenhouse wheeled around just 2.5 seconds after hearing a gunshot from behind him. Rittenhouse said he knew Rosenbaum didn’t have a gun, but he said he heard someone say “Get him” and “Kill him” as he was pursued, and Rosenbaum had previously threatened his life. Doug Kelley, the deputy chief medical examiner in Milwaukee County, testified that there was no conclusive evidence as to whether Rosenbaum was trying to grab Rittenhouse’s gun or swat it away as he closed in on Rittenhouse the moment before he was shot. While the prosecution argued that Rittenhouse provoked the incident by pointing his gun at Rosenbaum during an earlier verbal confrontation, the reason that may not have unraveled the self-defense argument for the jury is that he then chose to run away from Rosenbaum.

Rittenhouse stood over a man administering first aid to Rosenbaum for half a minute, then fled the scene. Rittenhouse was running away from a group of protesters who were identifying him as the shooter and yelling out things like “Cranium that boy!” and “Get him!” when the second set of encounters happened. Here’s a summary of what happened, per The New Yorker:

A demonstrator ran up behind Rittenhouse and smacked him in the head. When Rittenhouse tripped and fell, another man executed a flying kick; Rittenhouse fired twice, from the ground, and missed. Another demonstrator whacked him in the neck with the edge of a skateboard and tried to grab his rifle; Rittenhouse shot him in the heart. A third demonstrator approached with a handgun; Rittenhouse shot him in the arm, nearly blowing it off.

The jury had to decide whether in this situation Rittenhouse was trying to prevent great bodily harm or imminent death, and whether they were persuaded by the prosecution’s attempt to prove that Rittenhouse wasn’t acting in self-defense beyond a reasonable doubt. It appears they weren’t.

Given the complexity and fast-moving nature of the encounters and the high burden of convicting Rittenhouse under Wisconsin law, I’d argue that the decision might be distasteful but isn’t unreasonable; at the very least it’s not right to read it as a stamp of approval of Rittenhouse’s behavior.

In a more sane world with a different legal and cultural landscape, Rittenhouse would’ve been punished for his reckless behavior in some fashion, but that’s not the world we live in.

But there’s nothing incompatible between believing Rittenhouse’s acquittal made sense given the legal constraints and also believing that Rittenhouse behaved inappropriately and represents nefarious aspects of our culture.