By the time Arizona Republican Gov. Jan Brewer announced that she was vetoing SB 1062, a bill that would have made it easier for business owners to turn away gay and lesbian customers, the religious right had already lost.

“Religious liberty is a core American and Arizona value, so is non-discrimination,” Brewer said in a statement Wednesday. “The bill could could divide Arizona in ways we cannot even imagine and no one would ever want.”

Major corporations like Apple, Delta, and American Airlines voiced opposition to the bill. The National Football League was preparing to move the Super Bowl. And by the time Brewer put pen to paper Wednesday evening, it wasn’t just both Republican U.S. Senators from Arizona urging her to veto it. State lawmakers who had supported the bill were begging Brewer to save Arizona from themselves.

“I hope other fringe legislators will take a lesson from what’s happening in Arizona,” said Evan Wolfson, head of the LGBT rights group Freedom to Marry. “This is not about religious freedom, it was about creating a license to discriminate. It was wrong in the 60s with regard to race discrimination, wrong in the 70s in regard to women’s equality, and it’s wrong for America today.”

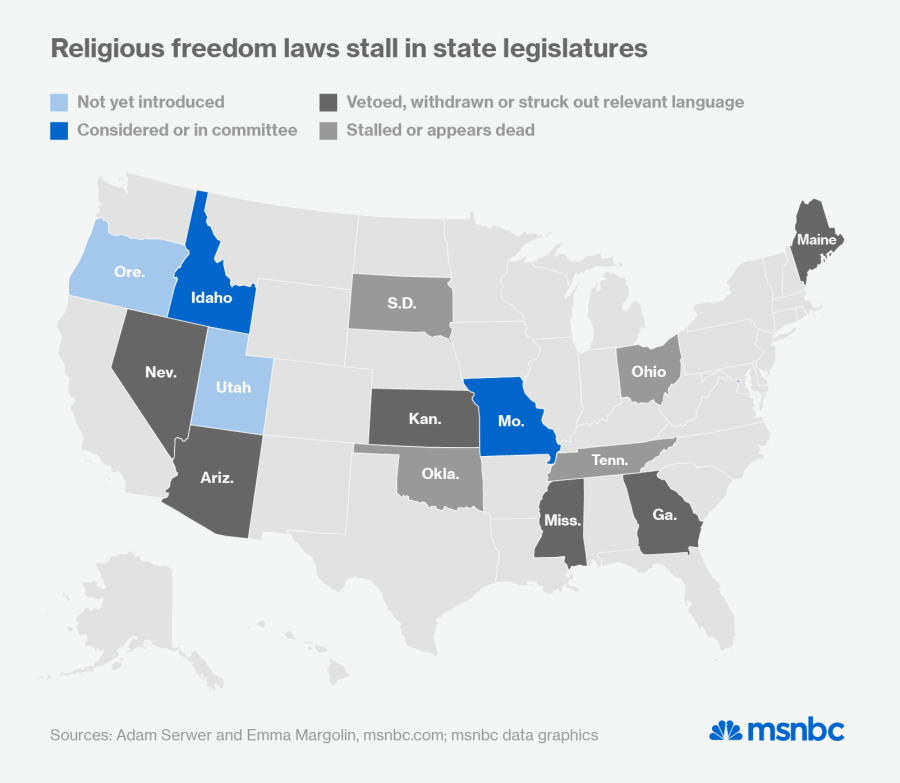

Brewer’s veto was only the latest defeat in the movement. In the past month, bills aimed at protecting business owners’ prerogative to refuse service to individuals based on their religious beliefs faltered in Kansas, Ohio, Mississippi, South Dakota, Idaho, Georgia, and Tennessee. Spurred on by cases in New Mexico and Colorado, where a photographer and a baker were told they couldn’t refuse customers on their religious objections to same-sex marriage, state legislators responded to a growing fear on the religious right that they are the ones suddenly becoming an unpopular minority whose fundamental rights are in danger.

“I think you’ve had a rise in hostility towards religion, and towards religious people in the public square,” says Brian Walsh, executive director of the American Religious Freedom Program, which helped write religious freedom legislation in Kansas and elsewhere. “It’s become increasingly acceptable to be negative towards religious people. It’s okay now to speak in a very negative way, especially if you can label them as haters.”

For LGBT rights activists, this feels like a tipping point. The Supreme Court’s decision striking down part of the Defense of Marriage Act has led to a flood of federal court rulings striking down bans on same-sex marriage. The swiftness and breadth of the backlash against the religious freedom laws in Kansas, Arizona and elsewhere, has bolstered a sense that the wind is at their back.

“You see these moments at real turning points for social change, the fact that this is happening is a testament that we are at a moment with how our society treats LGBT people and our readiness to take a big step forward,” says Louise Melling of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Conservatives felt blindsided by that same response, and betrayed by what they felt was misleading coverage of what their proposals actually did.

“I think there were a lot of well intentioned people who were acting on misinformation,” says Walsh. “When the torches and pitchforks come out in a seeemingly endless procession it makes it difficult for people to find out what the truth is.”

The truth is, though, that as far as sexual orientation is concerned, the attempt to carve out a broad religious exception to non-discrimination laws (in many cases, a preemptive one) was probably doomed from the start. Though conservatives insisted that the religious freedom bills were maligned as the reincarnation of Jim Crow, they were written so broadly that they could easily have been construed as a license to discriminate. Persuading Americans that you should be allowed to discriminate against gays and lesbians is a harder sell than telling them same-sex couples shouldn’t be able to get married.

A majority of Americans now favor same-sex marriage, in every region of the country except for the South. But non-discrimination is not just a majority position. It’s practically a foregone conclusion. According to a recent survey by the Public Religion Research Institute, 75% of Americans already think it is illegal under federal law to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation in employment. They’re wrong — there is no federal law barring discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Most states don’t ban it, including Arizona. People simply take for granted that it’s the case because an overwhelming majority — 72% — think it should be.

Had conservatives focused narrowly on the issue of services for same-sex weddings, they might have had an easier time. But only in Oregon was the language of their proposal that narrow. In every other state, they pursued a religious exception that would be broad enough to cover the caterer who does not want to provide food for a same-sex wedding and the shop owner who objects to paying for insurance that covers his women employees’ birth control. The result was a set of proposals so broad as to justify everything from a cop refusing to respond to a domestic violence call from a same-sex couple to a restauranteur telling a same-sex couple that their kind aren’t served here.

Conservatives used to be able to count on the influence of culture, if not the state, to enforce their views on homosexuality. That’s no longer true.

What changed first is a chicken-and-the-egg kind of question. But Walsh points to the Supreme Court’s ruling in a 1990 religious freedom case, rather than the more recent battle for same-sex marriage, as the catalyst for the current battle. In that case, Justice Antonin Scalia — not known as a champion of gay rights — wrote that religion could not serve to exempt people from “laws of general applicability.” Any other approach, Scalia wrote, would “make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and in effect to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself.”

“The Supreme Court essentially kicked religious freedom out of the pantheon of First Amendment rights,” says Walsh. “It told religious people they could no longer rely on the constitution, on the First Amendment, and would have to work through state legislatures.” This isn’t just about same-sex marriage for people like Walsh–but about a longstanding American tradition of respect for religion that he feels is slipping away.