Billionaire venture capitalist Tom Perkins raised the Internet’s collective eyebrows last week when he said Americans who don’t pay taxes — he likely meant income taxes — shouldn’t get to vote. (It didn’t help that Perkins had recently compared efforts to fight inequality to Kristallnacht).

“The Tom Perkins System is: You don’t get to vote unless you pay a dollar of taxes,” Perkins said during a speech in San Francisco. “What I really think is, it should be like a corporation. You pay a million dollars in taxes, you get a million votes. How’s that?”

The audience laughed, and Perkins later implied he was being deliberately provocative.

But the “Tom Perkins System” has its roots in some long-standing conservative thinking about the purpose of voting. And versions of that thinking continue to play a role in today’s heated debates over voter ID and other restrictive laws.

Progressives think of voting as a right. It’s the way a society of equals makes decisions. That’s why progressives generally see bringing new voters into the process as a good thing in itself. The more people involved, the more democratic the process, and the more legitimate the outcome.

But as the election law scholar Rick Hasen has written, many conservatives have tended to think about voting differently. For them, it’s a means to an end. And that end, an entirely reasonable one, is making an informed collective choice that will produce effective government and promote the common good.

That view of voting has deep roots in American history, scholars of U.S. democracy say. It’s how the citizens of the early Republic who gathered on village greens to vote in public, with the broad interests of the community uppermost in their minds, conceived of what they were doing. It’s no coincidence that of the 13 original colonies, the three most prominent — Massachusetts , Pennsylvania, and Virginia — to this day call themselves not states but commonwealths, political communities that were founded for the common good.

But from the start, that notion of voting for the common good paradoxically provided a rationale for excluding less-privileged groups from casting a ballot. In the years after U.S. independence from Britain, those who lacked property were barred from voting. The thinking went that non-property owners couldn’t be counted on to keep the common good in mind, and might sell their votes to the landowners on whom they depended.

By the 1830s, property-less white males were mostly enfranchised. But tax-paying requirements of the kind Perkins suggested followed in their wake for a while. And groups including blacks–not just slaves, but many who were nominally free–women, and later immigrants from eastern and southern Europe, would continue to be shut out in large numbers, with similar justifications used.

The historian Francis Parkman wrote in 1878 that a “New England village of olden time” could be “safely and well governed by the votes of every man.” But, he argued, this was no longer true now that those villages had grown into cities with “tenement-houses” and “restless workmen, foreigners for the most part.” For these people, Parkman wrote, “the public good is nothing and their own most trivial interests everything.” Under these conditions, “universal suffrage becomes a questionable blessing.” The passage is included in Alex Keyssar’s 2000 book The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States, probably the most comprehensive historical look at the subject.

A related justification was offered for the literacy tests that were used against both immigrants in the north during the late 19th and early 20th centuries and blacks in the Jim Crow south: that only the literate can be informed enough to be entrusted with the vote.

One obvious weakness of this view is that it ignores the reality that different groups have different interests–the rich may benefit from the policies of one candidate, the poor from those of another. So there’s no “common good” that serves everyone equally. But this aversion to the idea of interests, too, has deep roots, historians say.

Americans have generally believed that this society–unlike the multiple nations of Europe–enjoys a basic consensus on values. For instance, people believe in the legitimacy of private property. A system that prioritized the idea of interests, the thinking goes, would be more likely to cater to extremists who might not share those same values. That’s one major reason for our two-party system: to marginalize the extremes.

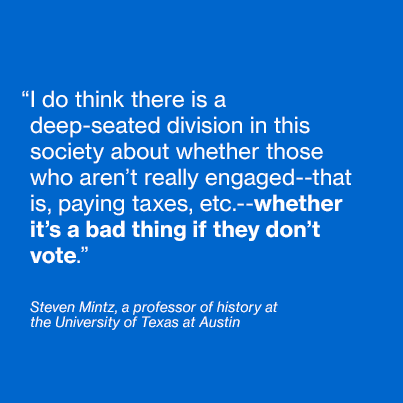

These conflicts over interests versus the common good, and over a broad electorate versus an informed one, aren’t as neatly resolved today as they might appear, said Steven Mintz, a professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin who has written in depth about access to the vote through history.

“I do think there is a deep-seated division in this society about whether those who aren’t really engaged–that is, paying taxes, etc.–whether it’s a bad thing if they don’t vote,” Mintz said. Some people think it isn’t so bad, he added, because those who are disengaged “would either vote out of ignorance or they would vote for extremist parties.”

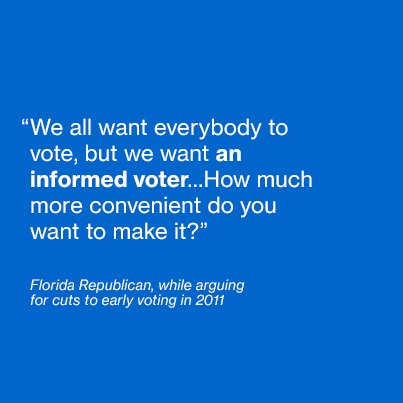

It’s not hard to find examples of what Mintz is talking about.

“We all want everybody to vote, but we want an informed voter,” one Florida Republican said while arguing for cuts to early voting in 2011. “How much more convenient do you want to make it?”

That’s not really a fringe position on the right.