Savor the blast of an air conditioner or down a glass of tap water and you might catch them: Legionella bacteria.

The pellet-shaped micro-organisms are the source of Legionnaires’ disease, a rapidly escalating public health threat, according to researchers. They live in warm, damp spaces, where they sometimes multiple into deadly airborne threats, as they have in New York City this summer.

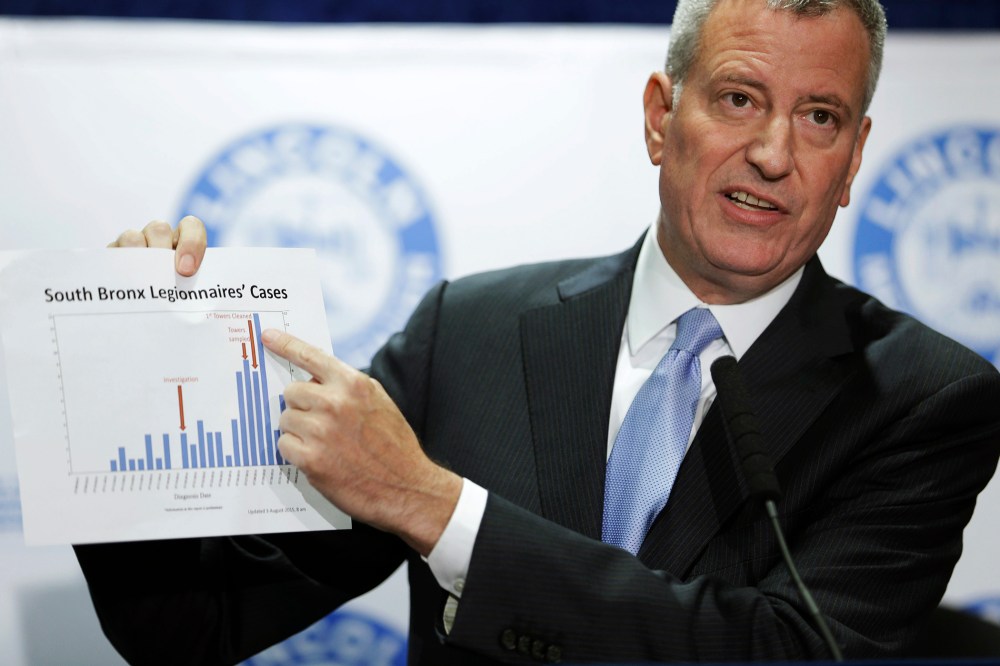

Since July 10th, nearly 100 people have caught the bug in the Bronx. At least eight of them have died. It’s the worst outbreak in the city’s history. But reported cases of Legionnaires’ disease have more than tripled since 2001, according to a new study in the Journal of Public Health Management Practice. Worse, the country is poorly prepared to prevent a still greater outbreak, the authors argued.

RELATED: 97 Sick, 8 dead in NYC Legionnaires’ outbreak: Officials

That study and another published in March also suggested that the latest epidemic may signal an incipient global problem, possibly tied to climate change. “Legionnaires’ disease should now be added to the IPCC’s list of important climate sensitive health issues,” Japanese researcher Ryota Sakamoto argued in a recent paper published by the World Health Organization.

The IPCC, or Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, has already warned that hotter temperatures and heavier rains could stir up killers from the edges of civilization. That’s recognized to include well-known diseases like dengue fever, West Nile virus, and malaria. Sakamoto believes Legionnaires’ disease deserves the same level of scrutiny.

The number of incidents is certainly on the rise. There were 3,522 cases nationwide in 2009, according to the most recent detailed data from the Centers for Disease Control. That’s more than double the count from a decade earlier. And preliminary data shows a continued spike to 4,548 cases in 2013, the more recent year that numbers are available.

New York City has seen a similar rise. The number of increased 230% from 2002 to 2009, with the greatest number in high-poverty neighborhoods, according to an October study in the CDC journal Emerging Infectious Diseases. The CDC now estimates that there are between 8,000 and 18,000 cases a year, nationwide. The Occupational Safety & Health Adminstration, meanwhile, provides an estimate of up to 50,000 cases annually.

Exact counts are impossible to come by, because they depend on reporting from local hospitals and doctors. But the increase is mirrored in Canada and Europe, and it raises the question of whether longer, warmer summers and more torrential rainfall has spread the disease.

The rise has been particularly visible in the mid-Atlantic, northeast, and Great Lakes Region, where the worst clusters have been associated with cruise ships, health club hot tubs, decorative fountains, supermarket produce mist, old pipes, new air conditioners, and the machinery atop city buildings. Basically, the disease is possible anywhere there is warm standing water, blown or misted into the air, or leaked into sinks, taps or showers. The disease can’t spread person-to-person like a cold—but it is airborne.