Official Washington is rife with talk about inequality—a theme that’s expected to be at the heart of President Obama’s State of the Union Address on Tuesday. But right outside Congress’ doors—east of North Capitol Street, across the Anacostia River, camped out on the steps of Union Station—the residents of D.C. are living it.

Alicia Burton, 47, lost her job doing payroll for a health-care firm last March and has been trying to find work ever since. Every morning, it’s been the same routine: “I wake up, I have my moment with God, then I get on a computer,” Burton says, dressed in the pink blouse and black pantsuit that she used to wear to the office. But the very same job that she got with her high school diploma now demands a Bachelor’s degree—effectively shutting her out of the running.

“They are competing against a higher skilled workforce, fighting for the same opportunity,” says Paulette Francois, D.C.’s deputy director of workforce development.

Burton is now among the thousands of District residents who’ve been unemployed for longer than six months—a group that makes up nearly half of D.C.’s 33,000 unemployed workers. Despite a new wave of prosperity that’s brought jobs and growth to the region, in the District, as elsewhere in America, many are being left behind.

“The Walmart they opened up here—it’s for the minimum wage person,” says Burton, who spent nine years doing administrative work in human resources before she was laid off. “It’s not for me, with my career.”

The disparity between D.C.’s new arrivals and its long-time residents is nothing new. But the differences have grown even more stark with the surge of young, highly educated workers, an unequal economic recovery, and the growing barriers facing the lifelong residents of a majority-black city.

“You have these minimum wage jobs that are less than full time, and there’s no way anyone can support themselves,” says Marina Streznewski, executive director of the D.C. Jobs Council. “On the other hand, you have these great jobs with benefits that require the minimum of a Bachelor’s degree.”

The gap between low- and high-income households in D.C. is one of the biggest in the country—the third-highest of the 50 largest cities in the U.S., according to the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute. While the D.C. metro area was spared the worst of the recession, the downturn and subsequence recovery have exacerbated the long-standing differences between the area’s rich and poor.

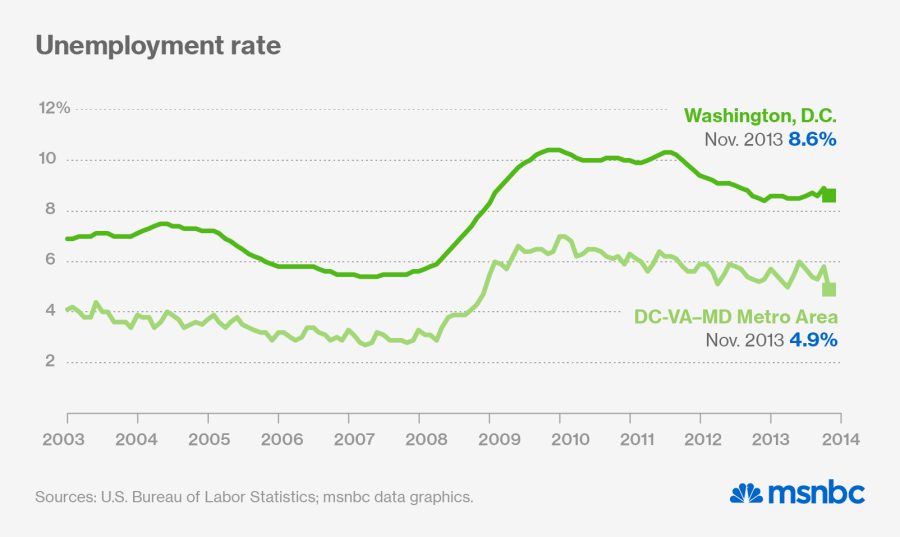

Between 2007 and 2012, 18.5% of D.C.’s residents were in poverty, compared to 8.4% in the entire metro region, which includes six of the 10 richest counties in the U.S. The massive growth in federal contracting dollars—hitting $80 billion in 2010 alone—helped push the median household income to nearly $120,000 in Virginia’s Loudoun County. But the disparities aren’t just in terms of income. While the region’s unemployment rate has dipped to just 4.9%—far below the national rate—it’s stuck at 8.6% in the District. Within the city itself, the differences are even starker: The jobless rate in Ward 8, one of the city’s poorest areas, is 18.6 percent; in tony Ward 3, it’s 1.8 percent.

Locally, the debate over D.C.’s inequities invariably turns to gentrification—the vegan bakeries, artisanal cocktail bars, and glass-walled lofts that have arrived as the District has added an estimated 44,000 people over the last three years. Local building restrictions have put even more upward pressure on the housing market in a city that remains intensely segregated. But D.C.’s poorer, less educated residents are also feeling the squeeze in the labor market, as the new money hasn’t been enough to overcome deep-rooted barriers to employment—and at times has made it even harder for D.C.’s less privileged residents.

White-collar workers without advanced degrees are finding it increasingly difficult to find jobs—or keep the ones they have. Over the last eight years, due to budget cuts and increasing automation, the federal government has eliminated 40,000 clerical jobs, many of which were held by women without college degrees.

“It used to be that the Government Printing Office was a wonderful job to have as a District resident,” says Jim Dinegar, president and CEO of the Greater Washington Board of Trade. “We’re not doing much printing any more.” It won’t be easy for many to re-enter the workforce, either: The jobless rate for D.C. residents with only a high-school diploma is 17 percent, while it’s 4 percent for those with a Bachelor’s degree, according to the DC Department of Employment Services.

In D.C.—as in the rest of America—such trends have hastened the disappearance of the city’s middle class: More than 45 percent of the area’s households make more than $100,000 a year, while one-third make less than $60,000, according to the New York Times. And the demand for even the lowest-paying jobs has been overwhelming: After opening its first two stores in D.C. in October, Walmart received more than 11,000 application for just 1,800 positions within the first week.

Among those still looking for work is Alvin Deese, 39, who lost his job as a retail clerk at a music store in Southeast D.C. after the entire complex was torn down for re-development. “It’s been strenuous,” says Deese, waiting at an unemployment office in D.C.’s Congress Heights, a leather folder tucked under his arm.