It’s the kind of deal that makes Washington’s old bulls nostalgic for days of Congress past: bipartisan, pragmatic, and swiftly pulled together behind closed doors to address an urgent policy problem.

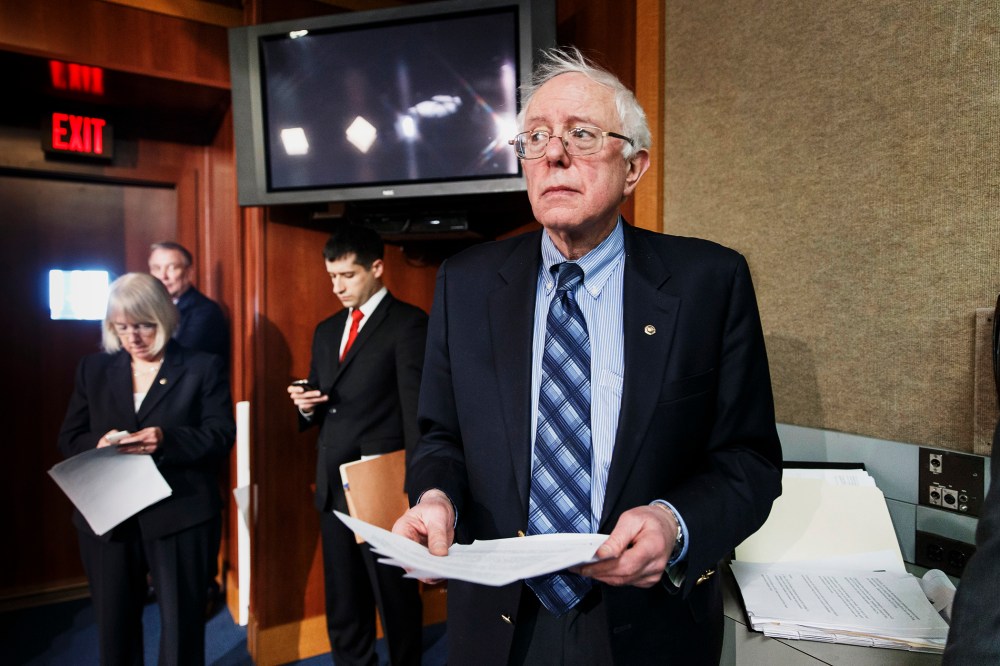

But the bill overhauling veterans’ health care, which passed both houses unanimously this week, had an unlikely legislator at the helm: Congress’s only self-described socialist, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who has long prided himself as being the left’s gadfly.

%22When%20you%20become%20chairman%2C%20you%20can%E2%80%99t%20just%20say%2C%20%27This%20is%20the%20way%20I%20want%20it.%22′

Sanders, who’s officially a political independent but votes with Democrats in the Senate, has spent far more of his career agitating from the sidelines than sitting at the negotiating table: lobbying for universal single-payer health care, blasting both parties for allowing billionaires to fund elections, and attacking President Obama for compromising on taxes with Republicans.

A co-founder of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, he prides himself on never forsaking his values and always speaking his mind—once for more than eight hours in a single stretch on the Senate floor.

But Sanders — who is almost universally known as “Bernie” — has found himself on the inside more often these days.

The bipartisan compromise that Sanders forged with Sen. John McCain, an Arizona Republican, came together with unusual speed, passing the Senate Wednesday after sailing through the House a day earlier. The scandal over wait times for veterans at VA medical facilities made made action a political imperative for Congress. But Sanders says he’s known he had to shift gears and become more open to compromise ever since he became chairman of the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee in 2013.

“When you become chairman, you can’t just say, ‘This is the way I want it,’” Sanders told msnbc.

It was Sanders’ first time working together with McCain, in a role that he’s rarely played before in his 23 years in Congress. As it turns out, he liked it.

“What I like about [McCain] is that he’s a no bullshit guy. He’s straightforward and he wanted to do something,” says Sanders. “I like that style of sitting down and saying, ‘I’m going to have to give, you’re going to have to give.’”

Sanders hasn’t always been as willing to make such concessions, says Alex Nicholson, legislative director for the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, an advocacy group.

“We’ve also, I think, had to push him to go outside his comfort zone in working with the minority. That’s definitely been a challenge,” Nicholson said. (Sanders says he “doesn’t recall talking about the negotiations with IAVA, which played no role in the agreement between Sens. Sanders and McCain,” according to his spokesman Michael Briggs.)

Though his group endorsed the bill at the time, Nicholson also faults the Vermont Senator for not doing more to work with Republicans on the earlier VA reform overhaul, which failed to pass in February after only two Republicans supported it.

Sanders says he’s still deeply disappointed that his original veterans’ reform overhaul failed to gain traction in the Senate. But he did make genuine concessions to Republicans in the compromise that passed Wednesday, including provisions he had criticized earlier that would allow veterans who lived more than 40 miles from VA facilities to seek private, non-VA alternatives.

It’s been a shift in tone as much as action for Sanders, the 72-year-old former Burlington mayor who became a member of the House in 1991 and the Senate in 2007. And for most of his political career, he’s been better known for exhorting Congress to act than taking action.

%22He%20may%20have%20mellowed%20a%20bit%20as%20he%E2%80%99s%20gotten%20older.%22′

Rising to protest President Obama’s tax compromise with Republicans in late 2010, Sanders launched into an epic speech on the Senate floor that took off on social media as the “filibernie.” It wasn’t so much a set of remarks as a great lamentation against what he described as “a war being waged by some of the wealthiest and most powerful people in this country against the working families of the United States.”

“How can I get by on one house?” Sanders continued sarcastically. “I need five houses, ten houses! I need three jet planes to take me all over the world! Sorry, American people. We’ve got the money, we’ve got the power, we’ve got the lobbyists here and on Wall Street. Tough luck. That’s the world, get used to it. Rich get richer. Middle-class shrinks.”

Compromise is easier, of course, when it comes to issues like veterans’ affairs, which have a long history of non-ideological bipartisanship. But in more recent years, Sanders has extracted a few genuine progressive victories, going beyond the purely symbolic amendments and dead-end bills that he’s accumulated over his career.

“Passing legislation has become more important for him,” says Vermont political scientist Eric Davis. “He may have mellowed a bit as he’s gotten older.”

During the fight over Obamacare, Sanders worked to include provisions to enable his home state to adopt single-payer health care, which it has now begun implementing under Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin.