Vietnam, or more accurately the fact of fleeing it, shaped my life. But we left when I was 3, so I have no memories of it — and unlike most of those trying to get out, I left as an American citizen. So in a big way, this story is really my mother’s.

It’s her I thought of when I saw the heartbreaking images of the Afghan people on the news in late August, her I think of as we learn about the early days of this new Taliban-led Afghanistan. Seeing Afghans’ despair, their desperation to get out of their country, hammers home more than ever how privileged I was to be an American citizen in Vietnam — and how lucky I am to have the life I live now in America.

I’m worried for the future of Afghan women and girls. Recently the director of the first all-women United Nations mission to Afghanistan proclaimed the country is “on the brink of total collapse,” warning that the “humanitarian imperative must come first.”

While there had been a push for more rights for women and girls in Afghanistan, comparatively. And now that push has been not only halted but reversed — instead of talking about education and career opportunities, now there’s great concern for simply their basic safety.

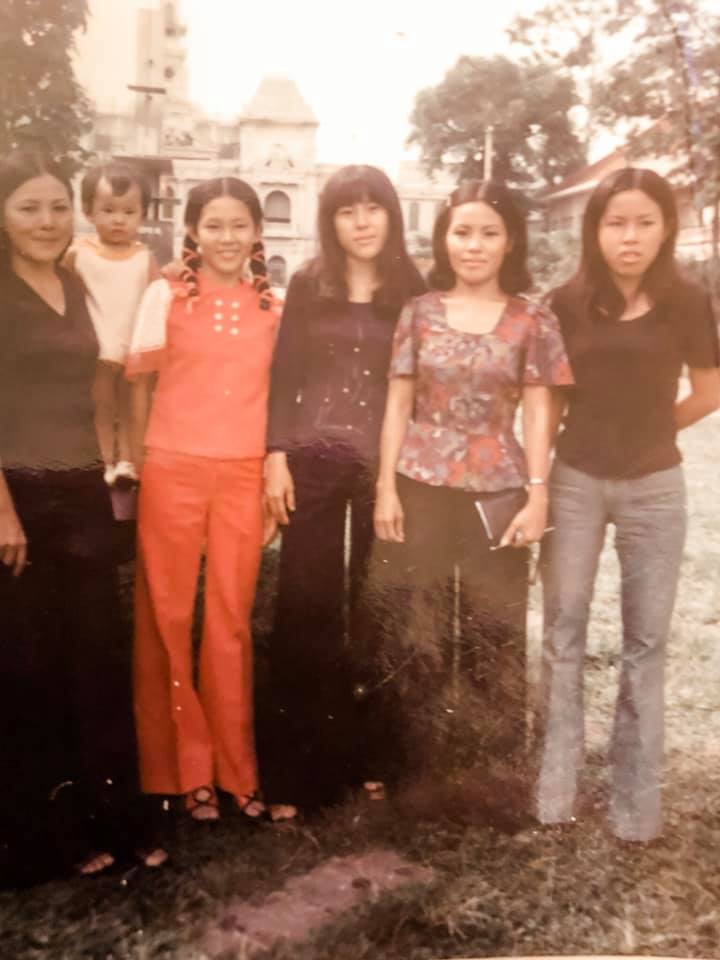

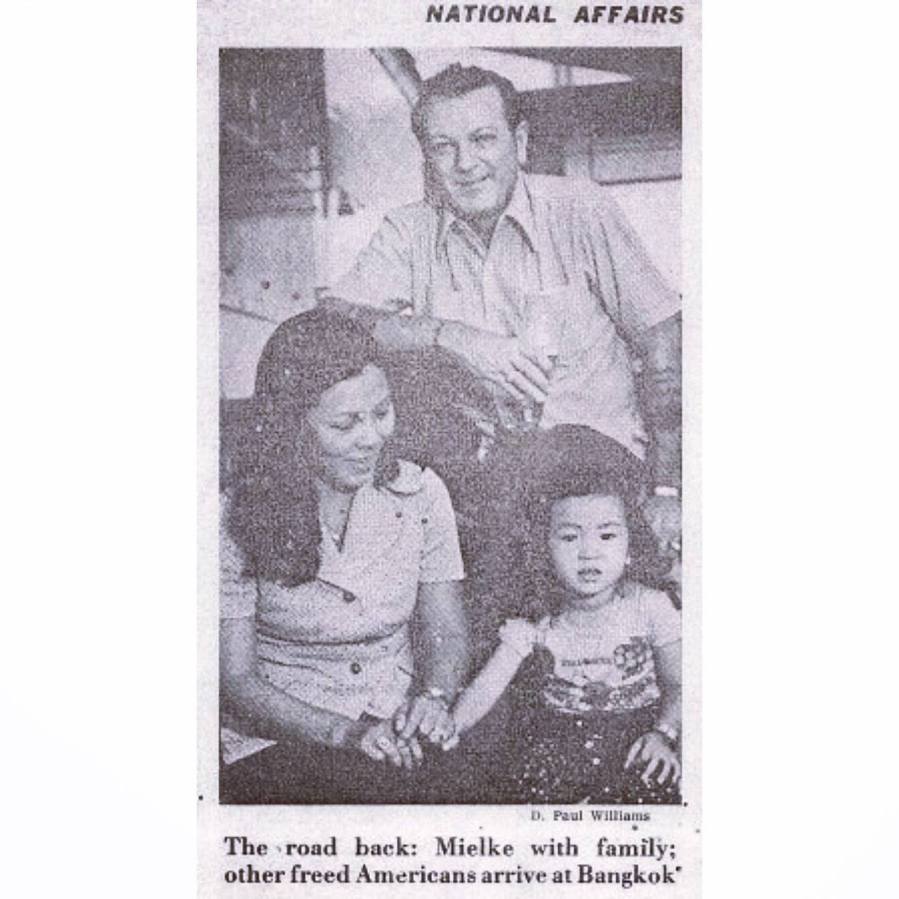

I was far luckier, as was my mother. She is Vietnamese, the oldest of nine children. My father was American, a former military man who had settled in Vietnam and was working for Voices in Vital America. They married, my mom became a naturalized American and about eight years after their wedding I came along.

And then, when I was 3, the fall of Saigon. American troops had withdrawn from the country in 1973; two years later, the communist government of North Vietnam captured South Vietnam’s capital on April 30, 1975.

The U.S. hadn’t expected Saigon to fall so quickly, and it scrambled to evacuate thousands of American citizens, South Vietnamese and others by military helicopter the day before and the day of Saigon’s capture. It was known as Operation Frequent Wind. We were one of the last American families to leave, so very privileged with our U.S. passports.

I don’t remember the evacuation, or Vietnam at all for that matter. But I do remember watching my mother’s resilience as she lived separated from her family for the next 15 years. And I know that though I had the good fortune to have an American passport, many of my fellow Vietnamese did not. They suffered great hardship to survive and so that future generations would have the chance to thrive.

That’s what’s on my mind as I look at Kabul. That’s true for my fellow Vietnamese-Americans, whether they fled their home or were born in the U.S. The common thread in our conversations is that we share a humanity for Afghan refugees because we know the devastation of a homeland lost and hopes vanquished.

I think often about how my particular path may have been altered if I had stayed in Vietnam. Here in America, I spent 20 years working in political campaigns; I’m now the CEO of the non-profit Asian Pacific American Institute for Congressional Studies and the founder of a political and non-profit consultancy called Arum Group.

What would my life have been in Vietnam? The possibilities were put into sharp focus for me when I went back right after the 2008 U.S. election. We went to Saigon and they had all the high-end stores there like Gucci and Louis Vuitton. But I also saw so many children around who looked school-age — not at school but instead out panhandling to try to survive. If I hadn’t been an American citizen, those could have been my children.