Laura Grieneisen and Liz Miller have a lot in common. Both are graduate students in biology at the University of Notre Dame, where they share an office, a lab, and a research focus. Their work on bacteria in baboons takes them to Kenya for months on end.

Each wants to prevent pregnancy. Each was told by her doctor that her long stretches in the field would make her an excellent candidate for an intrauterine device, or the IUD.

That’s where their paths diverged.

Grieneisen was able to stay on her parents’ plan under the Affordable Care Act through age 26, so she got her IUD at no extra charge, just before turning 27 in July.

But Miller is 29, and gets her health care through the university. Her on-campus doctor was barred from even prescribing the IUD, she said, because of Notre Dame’s adherence to Catholic teaching against contraception. The doctor sent her off-campus for the prescription, but even then, Notre Dame’s insurance wouldn’t cover it.

RELATED: Meet the Wheaton College feminists

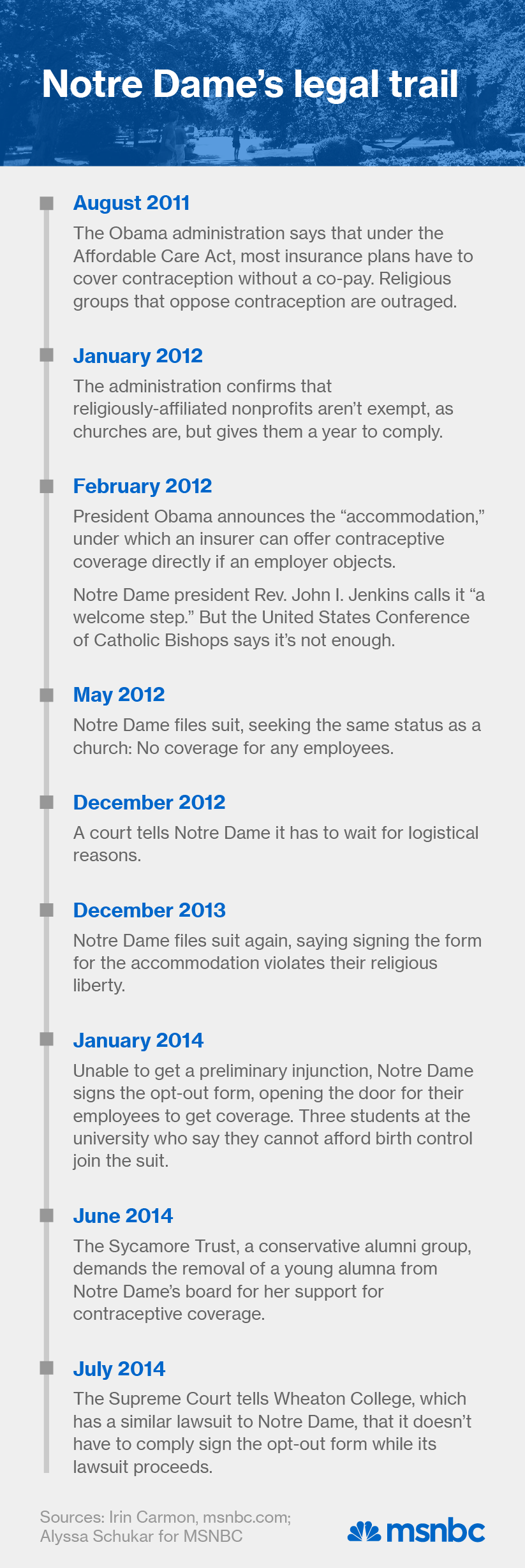

The Obama administration has a plan in place to cover women like Miller, who want access to effective but expensive forms of contraception like the IUD but who are insured through institutions that oppose it. The so-called “accommodation” allows religiously-affiliated nonprofits like Notre Dame to sign a form certifying their objection, after which the insurer will directly cover the cost of the contraception.

But in what promises to be the next big birth control fight after Hobby Lobby, that accommodation hasn’t satisfied Notre Dame — or over 100 other nonprofit institutions suing the administration. They claim that signing the opt-out form also violates their religious liberty, because eventually, contraception is dispensed.

On July 3, a majority of Supreme Court justices apparently took that argument seriously, telling evangelical Wheaton College, one of the plaintiffs suing the government, that it didn’t have to sign the disputed opt-out form while the lawsuit proceeded. That infuriated the female justices, who pointed out that days earlier, in the Hobby Lobby decision, the majority had called that accommodation “a system that seeks to respect the religious liberty of religious nonprofit corporations while ensuring that the employees of these entities have precisely the same access to all FDA-approved contraceptives as employees of companies whose owners have no religious objections to providing such coverage.”

The Hobby Lobby decision found that closely held companies with sincere religious beliefs could refuse to comply with the ACA’s contraception requirement. The majority relied on the existence of the accommodation as proof the government had other ways to provide contraception that didn’t, in their view, burden the companies’ religious liberty.

The ultimate question of the opt-out form won’t be settled until the Supreme Court gives it a proper hearing on the merits. For now, Miller is out of luck. The Notre Dame-affiliated insurance company refused to cover an IUD or its insertion, which together cost at least a thousand dollars.

“That’s over half my monthly salary,” said Miller.

Both Miller and Grieneisen chose Notre Dame to conduct advanced research with world class professors in their field. But the fight over birth control has disillusioned them, and they’ve begun warning prospective students about the lack of contraceptive coverage.

Miller is now struggling to get a three-month hormonal pill supply before she goes in the field next month. To even get a prescription for the pill, Miller had to fudge the truth and say she needed it for medical reasons, not birth control.

“I think it’s a really sad situation,” Miller said, “when I have to lie to my doctor about what I need a medication for.”

All the religious nonprofits suing over the contraceptive accommodation face the same conflict: Their fidelity to what they see as a religious mission and what they may owe their community members who don’t share that mission. And then there’s what the Obama administration wants: That under the ACA, every insured woman get access to effective, appropriate contraception without additional costs or hurdles.

%22I%20think%20it%E2%80%99s%20a%20really%20sad%20situation%20when%20I%20have%20to%20lie%20to%20my%20doctor%20about%20what%20I%20need%20a%20medication%20for.%22′

Notre Dame isn’t just the most prominent of the litigants; it’s also the one most visibly torn between those competing camps.

“I understand that Notre Dame is a Catholic institution and that birth control is not part of their Catholic beliefs, but not all the people who work for them are Catholic, and they don’t share the same beliefs,” said Kayla O’Connor, a rising junior at the university.

“There’s this mentality that Notre Dame students aren’t having sex,” added O’Connor, who is also a peer educator in the Gender Relations Center. “And that’s not true. It’s a total lie. I think because there isn’t easy access to contraceptives, they aren’t having safe sex.”

The tug-of-war at Notre Dame has gone all the way to the top, to its board of trustees and its president, The Rev. John I. Jenkins, who worked with the Obama administration on creating the accommodation but is now suing over it.

The board includes Stephen J. Brogan, a managing partner at the global law firm Jones Day, which is representing Notre Dame and the other nonprofits pro bono in the contraception lawsuits. And it includes Katie Washington, class of 2010 and Notre Dame’s first black valedictorian, who co-authored an op-ed in the Baltimore Sun with fellow medical students at Johns Hopkins University supporting the contraceptive coverage in the Affordable Care Act.

“We strongly disagree with any employer — religious or otherwise — that would refuse to provide full insurance coverage, including contraception, for its employees,” the authors, including Washington, wrote. “As physicians in training, we see contraception as an essential component of effective primary care, not as a political line item in Washington or the Vatican.”

Washington’s presence on the Notre Dame board and her outspoken public stand on contraception has enraged the Sycamore Trust, a conservative alumni group that has taken on the mission of “protecting Notre Dame’s Catholic identity,” according to its website. The Sycamore Trust has called for Washington’s ouster from the board, along with over 1600 people, who identify as “alumni, spouses, parents, students, and friends of Notre Dame” who signed their petition. (There is a smaller counter-petition asking the university to “maintain diverse viewpoints.)

Washington’s board membership has “handed the government a loaded gun in its lawsuit,” by undermining the university’s commitment to Catholic teaching on contraception, the Sycamore Trust’s chair, Bill Dempsey, said.

“Why she would be appointed is a mystery to me,” Dempsey told msnbc, adding that if Notre Dame hadn’t known about the op-ed, “they didn’t do any vetting at all. If you just plug in ‘Katie Washington and contraception’ into Google, that just comes up.”

In 2011, another Notre Dame board member resigned after the Sycamore Trust drew attention to her donations to EMILY’s List, a group that elects pro-choice Democratic women.

Washington declined to comment, but Paul Browne, a spokesman for Notre Dame, defended the university’s decision to keep her on the board.

%22You%20could%20look%20up%20and%20down%20all%20over%20the%20campus%20and%20you%20couldn%E2%80%99t%20find%20a%20box%20of%20condoms%20anywhere%20…%20I%20know%20a%20lot%20of%20people%20just%20didn%E2%80%99t%20use%20birth%20control.%22′

Notre Dame was present at the creation of that very opt-out form. When the birth control accommodation was first announced in the wake of an outcry from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, President Jenkins called the compromise a “welcome step toward recognizing the freedom of religious institutions.” But when that statement ended up on the White House’s website alongside Planned Parenthood’s, the university asked for it to be taken down. And then Jenkins decided to file suit over it.

“It was a tough decision,” Jenkins told the National Catholic Reporter. “Many people in the [Obama] administration worked with us. In the end, I wasn’t comfortable with where it placed Notre Dame.”

Jenkins had already enraged the more conservative members of the Notre Dame community for welcoming Obama to campus as a commencement speaker in 2009. Obama’s appearance and honorary degree are listed as a grievance by the Sycamore Trust, along with “other unsettling events as The Vagina Monologues and The Queer Film Festival.”

The group also points to the hiring non-Catholic faculty as a dilution of the university’s identity. “It’s been the ambition to improve their reputation among the academic elite, and boost their US News ranking,” Dempsey told msnbc.

But there are also those on campus who believe that offering contraceptive coverage doesn’t violate broader Catholic principles, and that respecting the different choices of community members is consistent with those principles.

“We should ask not just, ‘what are my beliefs?’” said Cathleen Kaveny, a Catholic legal scholar at Boston College who until January taught at Notre Dame’s Law School, “but also, what do I owe the sincerely-held religious beliefs of others in network with me?”

On a February morning in Chicago, two out of three federal judges on the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals hearing Notre Dame plead its case against signing the form were fast losing their patience.

“I don’t understand you,” Judge Richard Posner said testily. “You’ve got to claim the exemption…. So you have to notify the government. That’s the minimum.”

Arguing before the panel was attorney Matthew Kairis, a former Notre Dame football player and now a partner at the Jones Day firm.

Each time Kairis attempted to explain the university’s position — that the form would trigger contraceptive coverage, in violation of the university’s religious beliefs – Posner, a Reagan appointee, became more furious. He told Kairis to “stop fencing,” and to “stop babbling.”