Although it’s been five decades, Claude Summers and Ted-Larry Pebworth still remember perfectly the night they met.

The two were in the Boulevard Lounge, a gay bar in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in the summer of 1963—six years before riots at the Stonewall Inn in New York City effectively launched the modern gay rights movement. Ted was a 27-year-old Ph.D. candidate at Louisiana State University. Claude was 18, home for the summer after finishing his freshman year at UCLA.

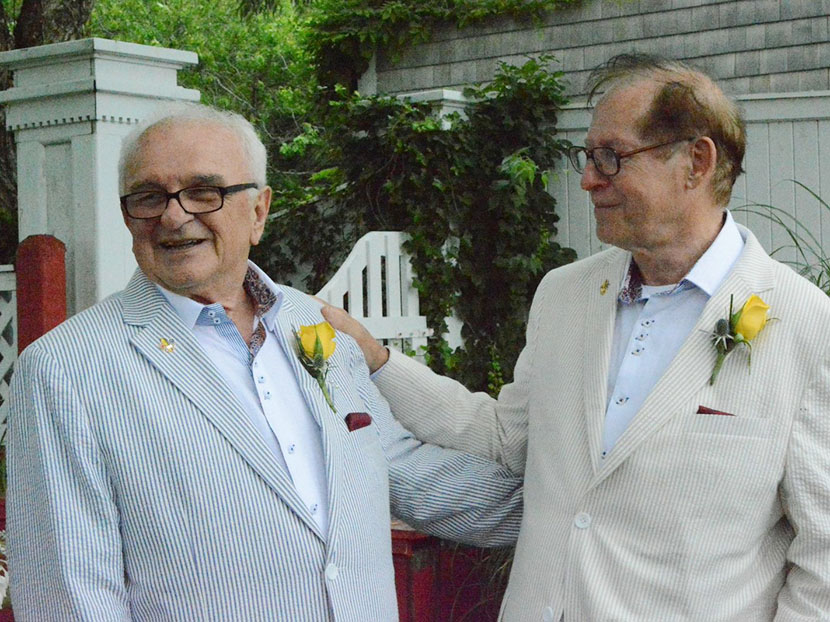

“He accuses me of robbing the cradle,” said Ted, now 77, in his Southern drawl. “It was pretty much love at first sight.”

As Claude tells it, the most important decision he anticipated having to make that summer was whether to major in English or pre-law. He never could have imagined the man who bought him a beer that night and talked to him about Tennessee Williams would eventually become his spouse.

On Thursday, nearly 50 years to the day after they first met, Claude and Ted are tying the knot. Not only will the wedding commemorate their golden anniversary—a time when most couples would be renewing their vows, not saying them for the first time—but it will also mark the Supreme Court rulings on two historic marriage equality cases.

For the couple whose relationship has spanned the entire gay rights movement, the decision to marry bridges the political with the deeply personal.

“We just decided that marriage was something both public and private,” said Claude, now 68, whose Louisiana accent rivals that of his soon-to-be spouse. “We don’t need the government for our private relationship, but we wanted to stand with our community and have our relationship honored the same way heterosexual relationships are.”

Claude and Ted are now back in Louisiana, retired after 30-year careers as English professors at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. But their wedding will be held in Provincetown, Massachusetts—the first state to legalize marriage equality through a state Supreme Court ruling nearly a decade ago. Though Louisiana does not recognize same-sex marriages, even those which took place in states that do, the decision to marry in Massachusetts seemed “very natural,” said the couple.

“I was struck by the Goodridge decision, in which the Massachusetts Supreme Court said there can be no second-class citizens, and therefore only marriage would suffice,” said Claude. “So we see it as not only public affirmation for our love to one another, but as a way of asserting our right to first-class citizenship.”

“There is value in having your relationship authorized, in a way,” said Ted. “Especially for gays, who have been denied that right. So that’s the thing I’m most happy about.”

Thursday’s wedding will gather about 40 friends from the couple’s happy life together.

Ted grew up in Homer, Louisiana, “one of the buckles on the Bible belt,” as he describes it. His mother found it hard to accept her son’s sexuality. She used to send Ted newspaper clippings of raids on gay bars. But Ted’s father was surprisingly supportive, even insisting that his son and Claude share a room the first time they came home together for the weekend.

“I never regretted being gay,” said Ted. “I thought everybody should just let me alone, and I’d let them alone.”

Claude, who grew up in Gonzales, Louisiana, said his mother was welcoming, too.

It wasn’t until after 1970 that the couple faced real homophobia that threatened the relationship. The pair was living in Chicago when Claude received a teaching job offer in California. Ted accepted a position there as well. But shortly after, Claude’s offer was rescinded when his employer found out about his sexuality, and the couple was forced to spend a year away from each other.