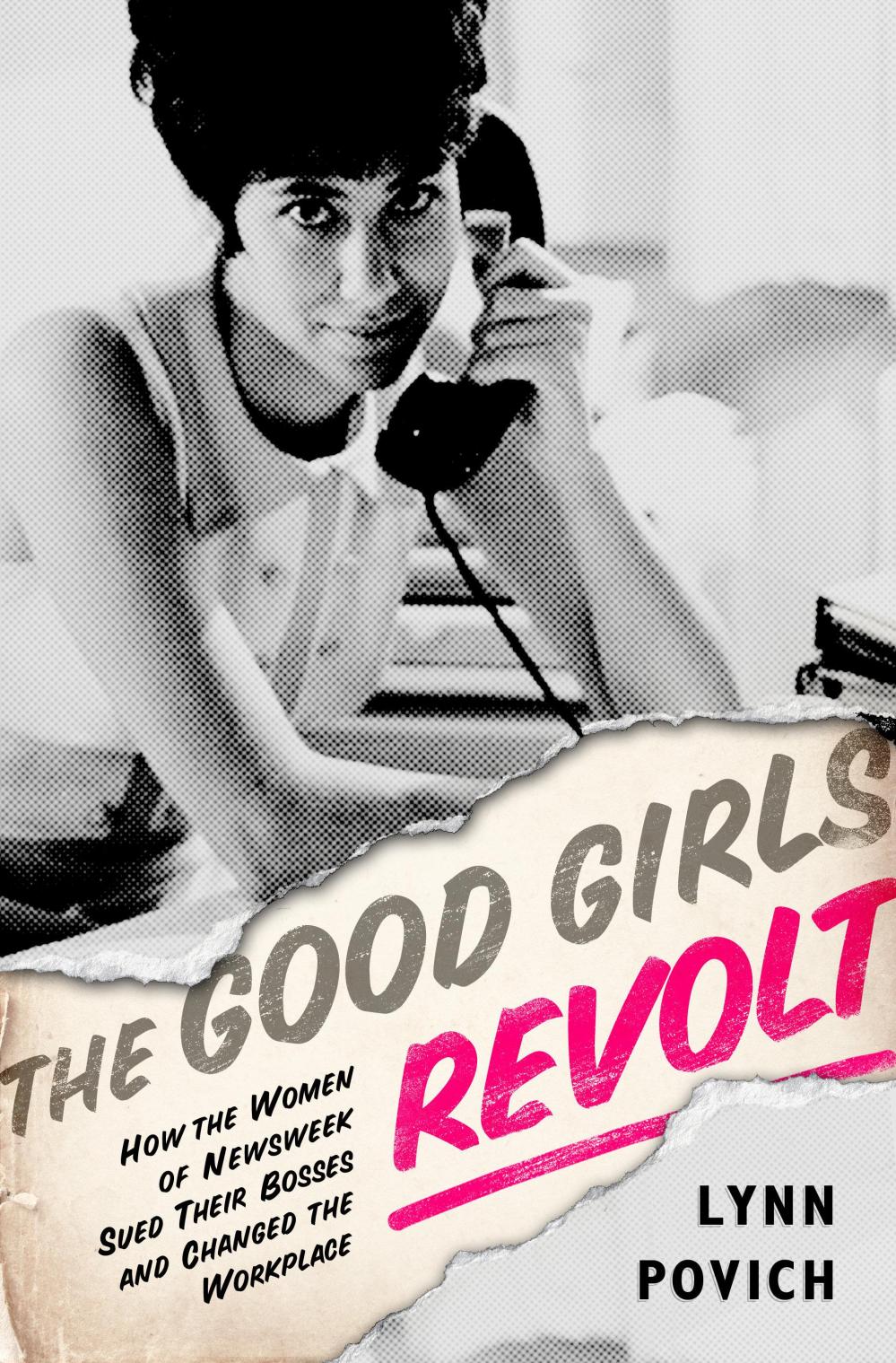

Lynn Povich, author of The Good Girls Revolt: How the Women of Newsweek Sued Their Bosses and Changed the Workplace, joins The Cycle today to discuss her book. Lynn recaps how along with 45 of her female colleagues they secretly banded together and filed a discrmination complaint, the same day as Newsweek, ran a cover story on the feminist movement. Her book is the story of how the women in the 40’s and 50’s stood up and demaned their rights. Lynn also explores the obstacles that still remain in the workplace for women.

Be sure to tune in at 3:40pm for the full conversation and check out an excerpt from her book below.

From the book The Good Girls Revolt by Lynn Povich. Reprinted by arrangement with PublicAffairs, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2012.

When Newsweek’s Editor-in-Chief, Osborn “Oz” Elliott, responded to our lawsuit that Monday in March, he released a statement that served only to confirm the institutional sexism of the magazine. “The fact that most researchers at Newsweek are women and that virtually all writers are men,” it said, “stems from a newsmagazine tradition going back almost fifty years.”

That was true—and most of us never questioned it. Although we held impressive degrees from top colleges, we were just happy to land a job—even a menial one—at an interesting place. Saying you worked at Newsweek was glamorous compared to most jobs available to college-educated women. Classified ads were still segregated by gender and the listings under

“Help Wanted—Female” were mainly for secretaries, nurses, and teachers or for training programs at banks and department stores such as Bloomingdale’s (that wouldn’t change until 1973, when the US Supreme Court ruled sex-segregated ads were illegal). But compared to jobs at newspapers, where women were reporters and editors—even if they were ghettoized in the “women’s pages”—the situation for women at the newsmagazines was uniquely injurious. We were confined to a category created especially for us and from which we rarely got promoted. Not only was research and fact-checking considered women’s work, but it was assumed that we didn’t have the talent or capability to go beyond it.

That infamous “tradition” began in 1923, when Henry Luce and Brit Hadden founded Time, The Weekly News-Magazine. Positioning their publication between the daily newspapers, which printed everything, and the weekly reviews, which were filled with lengthy commentary, these two young Yalies decided to create a conservative, compartmentalized digest of the week’s news that could be consumed in less than an hour. But although Time would give both sides of the issues, it would, they said in their prospective, clearly indicate “which side it believes to have the stronger position.” In the beginning, the magazine was written by a small group of their Ivy League friends, who distilled stories from newspapers and wrote them, echoing Hadden’s beloved Iliad, in a hyphenated news-speak (“fleetfooted Achilles”) and a backward-running sentence structure

(“Up to the White House portico rolled a borrowed automobile”). Time didn’t hire “stringer correspondents” until the 1930s, when the magazine decided to add original reporting.