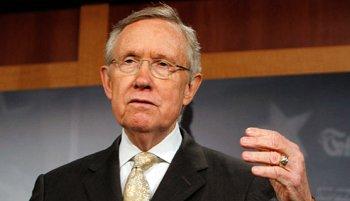

We don’t yet know exactly why Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) gave up on ambitious reforms of filibuster rules. After months of voicing support for sweeping changes, it’s possible Reid just didn’t have the votes from his own caucus to pursue bold reforms through the “constitutional option.”

Whatever the reasoning, however, it’s important that folks understand that when Reid says protecting the filibuster is necessary to keep the Senate from being like the House, he’s wrong.

“I’m not personally, at this stage, ready to get rid of the 60-vote threshold,” Reid (D-Nev.) told me this morning, referring to the number of votes needed to halt a filibuster. “With the history of the Senate, we have to understand the Senate isn’t and shouldn’t be like the House.”

I get the argument — the rambunctious House operates by majority rule, while the staid and serious Senate seeks consensus by requiring supermajorities for everything. Without the filibuster, the Senate is little more than a smaller version of House.

Except, this just isn’t true, and Reid’s explanation rings hollow. If his principal concern is with “the history of the Senate,” he should be more inclined to pursue real filibuster reform, not less.

First, let’s note the basics. Historically, the Senate differed from the House, not because of mandatory supermajorities that didn’t exist up until very recently, but because members serve six-year terms (instead of two) and represent entire states (instead of districts). The whole point was to create a deliberative institution — longer terms were intended to give members longer and less reflexive perspectives, and representing states helped guarantee more diverse constituencies.

The Senate didn’t need filibusters to be distinct from the House; the differences were baked into the cake.

But we can dig deeper.

Reid says he’s concerned about “the history of the Senate,” but the Senate functioned quite well for 200 years while remaining a majority-rule institution. There were, to be sure, procedural hoops to jump through, but if a bill reached the floor, and a majority of the Senate’s members supported it, the bill passed. That’s no longer true, and today’s modest reforms won’t even try to fix that problem.