In an effort to defend her state’s controversial new voter ID law last year, Texas State Rep. Debbie Riddle offered a memory.

She’d once seen a Latino woman at a polling place who needed assistance because she couldn’t speak English and seemed unfamiliar with the process, Riddle recalled during a legal deposition.

The law was being challenged by the federal government, and Riddle was asked to offer specific incidents of voter fraud that justified the new rules.

Riddle, a Republican who has been a leader of Texas’s efforts to make voting harder, said she had no idea whether the woman she saw that day was a citizen or not, or even whether she had ultimately voted.

“She was not only limited in English, she really didn’t know any English,” Riddle recalled. Riddle said the incident left her “perplexed [as to] how anyone could come in and attempt to vote and have just a complete disconnect of the entire process.”

Riddle’s suspicions at the ballot box put her at the cutting edge of her party’s strategy on voting rights. While the national GOP has said it will focus on reaching out to Latinos, Republicans on the ground have taken a very different tack: In recent years, a host of voter suppression measures across the country—from purges of voter rolls, to citizenship requirements to ID laws like the one Riddle backed in Texas—have appeared to target Latinos.

“Voter suppression laws and policies threaten to relegate Latino voters to second-class citizenship and impede their ability to participate fully in American democracy,” warned a 2012 report on Latino voter disenfranchisement by the Advancement Project, a civil-rights group.

Rep. Raul Grijalva, an Arizona Democrat, was more succinct. “It’s pretty obvious to me who the target is,” he told msnbc.

Since the civil-rights movement, the public face of voter disenfranchisement has generally been black. African-Americans have been more systematically victimized by efforts to restrict voting than any other group. But while blacks last year appeared to recognize that they were the targets of restrictions on voting, and responded by turning out at a rate few pollsters expected, advocates for Latinos say many don’t yet understand that their rights are at risk.

“There is a lot more work to do in the Hispanic community to get them to connect the dots between the voter suppression movement and their emerging political power,” Juan Cartagena, the president of Latino Justice, told msnbc.

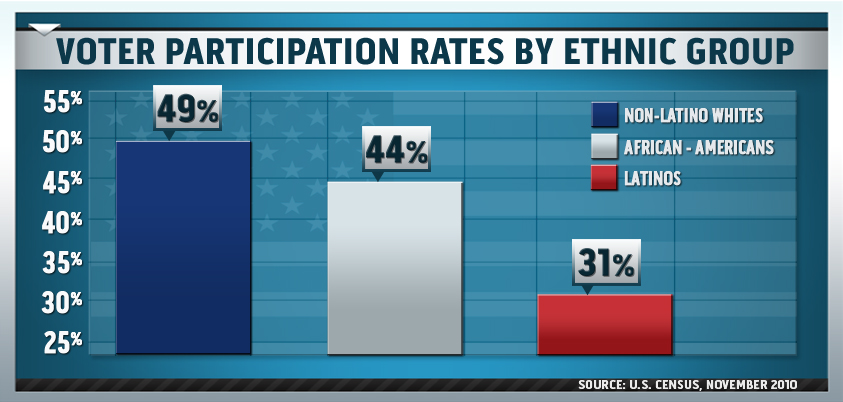

It’s no coincidence that these threats to Latino voter participation come at a time when the group’s political power is growing rapidly. Latinos now make up 10% of all eligible voters in the U.S., and with 60% of all new citizens in the coming years projected to be Latino, it’ll soon be much more. And because Latinos still punch far below their numerical weight—in 2010, just 31% of eligible Latinos voted, compared to 49% of non-Latino whites and 44% of African-Americans (see chart below)—they’ve got plenty of room to grow.

“We are seeing more intense efforts to block the growth of the electorate in states with greater Latino numbers,” Nina Perales, the top lawyer for the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund, told msnbc. “With greater Latino participation in the electorate, we are also seeing push-back from states.”

Nor is it likely a fluke that the Republican-led effort is intensifying at a time when Latinos may be poised to become a reliable part of the Democratic coalition, after being seen for decades as a legitimate swing vote. Last fall, more than 70% of Latinos supported President Obama, furthering a move toward the Democratic party that has been underway for several years.

As the targets of these voting crackdowns have expanded to include Latinos, so too has the rationale used to justify them, which now often focuses on the need to prevent non-citizens from voting. But, as with other forms of alleged voter fraud, there’s little evidence to suggest that’s happening. A lengthy investigative report by the Carnegie-Knight initiative found just 56 accusations of non-citizens voting since 2000. Of those, just one ended in a conviction.

Still, broad efforts targeting non-citizens are the next big thing in the “election integrity” movement. Hans Von Spakovsky, a Republican lawyer who has done perhaps more than anyone else to push the case for photo ID and similar measures, told PBS last year that laws requiring that people registering to vote first prove their citizenship are “the very next stage after photo ID.”

In fact, that stage is already well underway. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court heard a challenge to Arizona’s Proposition 200, passed in 2004, to prevent non-citizens—most of whom are Latino—from voting, by requiring that people provide documentation proving their citizenship when they register. The federal voter registration form already requires users to attest, on penalty of perjury that they’re a citizen. But thanks to Prop 200, Arizona has rejected more than 30,000 federal forms that don’t provide the additional citizenship documentation, according to opponents of the measure.

Arizona was ahead of the curve. Since 2011, Georgia, Alabama, and Kansas have passed similar measures. And in Michigan’s primary last year, Republican Secretary of State Ruth Johnson added a citizenship confirmation checkbox to ballot applications, creating confusion and keeping some legitimate voters from the polls, according to reports.

A recent Rasmussen poll found that 71% of respondents support requiring people to prove their citizenship when registering. In a statement to msnbc, Catherine Engelbrecht, the president of True the Vote, a Tea Party offshoot that stokes fear over voter fraud, noted that Mexico and Canada require proof of citizenship or naturalization, and called such laws “far from radical.”

But the push for these measures is being led by some of the same people behind recent efforts to target illegal immigrants more broadly. The Alabama measure was part of a larger law cracking down on illegal immigrants—it prevents them from receiving benefits, and encourages law enforcement to probe people’s citizenship status. Both the Alabama voting measure and the Kansas law, on which Alabama’s was closely based, were written by Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, who also wrote Arizona’s controversial “Papers Please” law, parts of which were rejected by the Supreme Court last year.

“Their attitude is us versus them,” Grijalva said. ” ‘Us’ being, we’re the good Americans, they’re the new, bad Americans. And what can we do to minimize their influence in the political sphere?”