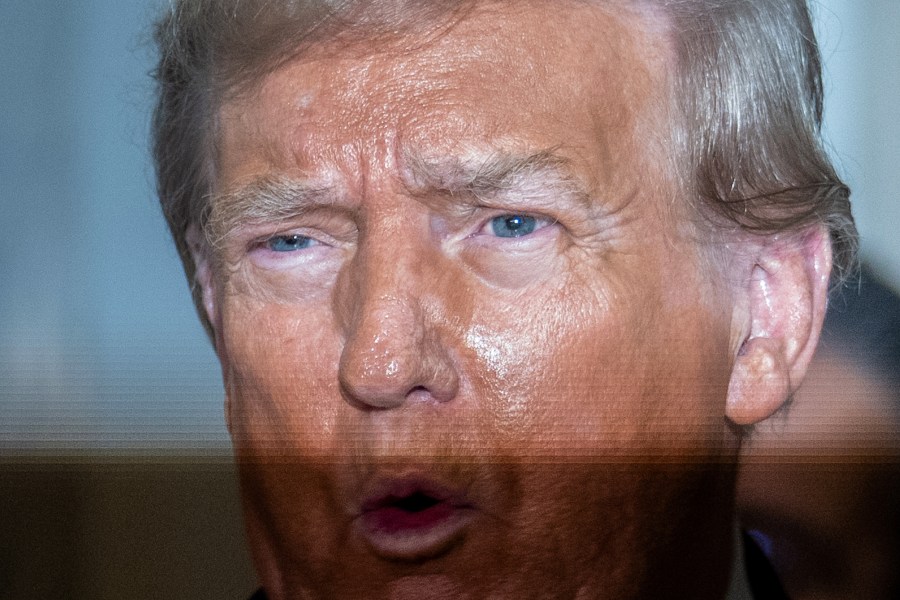

Former President Donald Trump has offered up some questionable arguments to try to squirm out of legal trouble before. But his latest argument may be the boldest yet. Trump is claiming that it’s unconstitutional to proceed with the federal case charging him with trying to overturn the 2020 presidential election and subvert lawful votes because he was acquitted for those same activities in his second impeachment trial.

In an amazing bit of spin, Trump’s team treats the word “convicted” as his get-out-of-jail-free card.

That argument was included in one of three motions to dismiss that Trump’s lawyers filed Monday night. Claiming, as Trump’s team does, that “the impeachment and double jeopardy clauses both bar retrial before this Court and require dismissal” requires a willful misunderstanding of the impeachment process.

Trump’s lawyers focus on Article I, Section 3, of the U.S. Constitution, which deals with the possible sentences for impeachment convictions, specifically the part that reads, “the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.” You might read that and think that it’s bad for Trump, as it clearly implies that an official who’s been impeached can be criminally charged. But, in an amazing bit of spin, Trump’s team treats the word “convicted” as his get-out-of-jail-free card. According to Trump’s motion: “As the Senate acquitted President Trump, the prosecution may not re-try him in this Court.”

That’s incredibly wrong for several reasons. First, there is a very clear distinction between impeachment trials, which are political, and criminal trials, which ought not to be. There is no standard in a Senate impeachment trial that comes close to the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard in a criminal case. Nor is there any need for unanimity among the jury as in federal criminal cases, as only two-thirds of senators are required to vote in favor of conviction — which thanks to partisanship can be an even higher bar.

According to the Constitution, the required punishment for an official convicted in an impeachment trial is removal from office. The other, optional sentence is to be barred from holding any future office, a punishment that would have blocked Trump from his current presidential run. In the federal criminal case charging him with trying to overturn the 2020 election, Trump is charged twice with a crime that carries a maximum prison sentence of 20 years, once with a crime that has a maximum 10-year sentence and once with a crime that has a maximum five-year sentence.

The idea that the Senate’s trial of Trump — where acquittal was a foregone political conclusion, divorced from the facts that a criminal trial requires — put him “in jeopardy of life or limb” makes no sense. He was in danger of, at most, not being able to hold office again, not any sort of jail time or monetary fine. And even then, Senate Republicans claimed (incorrectly, in my view) that because Trump had left office by the time of his second impeachment trial, he couldn’t be convicted in the upper chamber but that the regular courts would be able to sort things out. As Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said in his speech after voting to acquit, “We have a criminal justice system in this country. We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being held accountable by either one.”