With President Donald Trump flooding the zone with attacks on American democracy and the rule of law, it’s easy to lose sight of the damage that the Supreme Court is doing on its own to weaken voting rights protections. Late on a Friday afternoon in August, the Supreme Court — on its own initiative and via a cryptic order — transformed a ho-hum redistricting case into a potential vehicle to take down the remaining key section of the Voting Rights Act.

The case, which concerns the drawing of Louisiana’s six congressional districts, could decimate minority representation in Congress and state and local government. And if the court rules quickly enough, it may even allow yet another round of partisan redistricting that could affect which party controls Congress after the 2026 midterm elections. Yet few outside of Supreme Court lawyers and voting rights experts seem to be paying much attention.

Rather than resolve the “race or politics” question before the end of its 2024-25 term, the court took a very unusual step.

On Oct. 15, the Supreme Court will hear a second round of arguments in Louisiana v. Callais. After the 2020 census, Louisiana redrew its lines so that only one of its six districts was a district in which Black voters had an opportunity to elect candidates of their choice. Black voters sued, arguing that they made up about 35% of the population of Louisiana and the state was required under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to create a second majority-Black district. The courts agreed, and the Louisiana state Legislature reluctantly drew a new map creating that district while also protecting many Republican incumbents (including Speaker of the House Mike Johnson).

The drawing of that second “Black opportunity district” spurred the Callais lawsuit, in which white voters claimed that the new district was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander that violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Since the 1990s, beginning with the case of Shaw v. Reno, the Supreme Court has held redistricting to be a racial gerrymander when race, rather than politics, predominates in the drawing of district lines, and the state has no compelling reason to draw a race-predominating district.

When the Supreme Court first considered Callais back in March, Louisiana defended the second majority-Black district by saying that politics, rather than race, predominated. (Never mind that this is a nonsensical question in a state like Louisiana, where most white people prefer the Republican Party and most Black people the Democratic Party). But rather than resolve the “race or politics” question before the end of its 2024-25 term, the court took a very unusual step: It ordered the case be reargued the following term and promised it would issue a follow-up order “specifying any additional questions to be addressed in supplemental briefing.” (Justice Clarence Thomas dissented, wanting the court to attack the Voting Rights Act immediately.)

Then, after 5 p.m. on Aug. 1, the court asked the parties, albeit obliquely, to brief the following question: whether, if Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act required the drawing of that second Black opportunity district, was Section 2’s race-conscious remedy itself unconstitutional.

At this point, Louisiana flipped sides: it now argues that either Section 2 is unconstitutional or it should be read in such a way as to sap Section 2 of its power to protect minority voting rights. In this argument the state was joined not just by 16 states, but also by the United States Department of Justice, which under previous Democratic and Republican administrations had repeatedly defended the constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act.

To understand the stakes, we need to go back to the VRA’s origins. The original Voting Rights Act contained a pre-clearance provision that required states and counties with a history of racial discrimination in voting to get federal approval before changing their voting rules. These jurisdictions had to show that the changes would not make minority voters worse off.

Pre-clearance was key to stopping a retrogression of voting rights in the American South and elsewhere, but it was not enough to give minority voters a fair shot at political success. When white and minority voters preferred different candidates for office, the former could still shut the latter out of the political process. That’s what happened in Mobile, Alabama, where Black people had no representation on their at-large city council, despite being one-third of the city’s population.

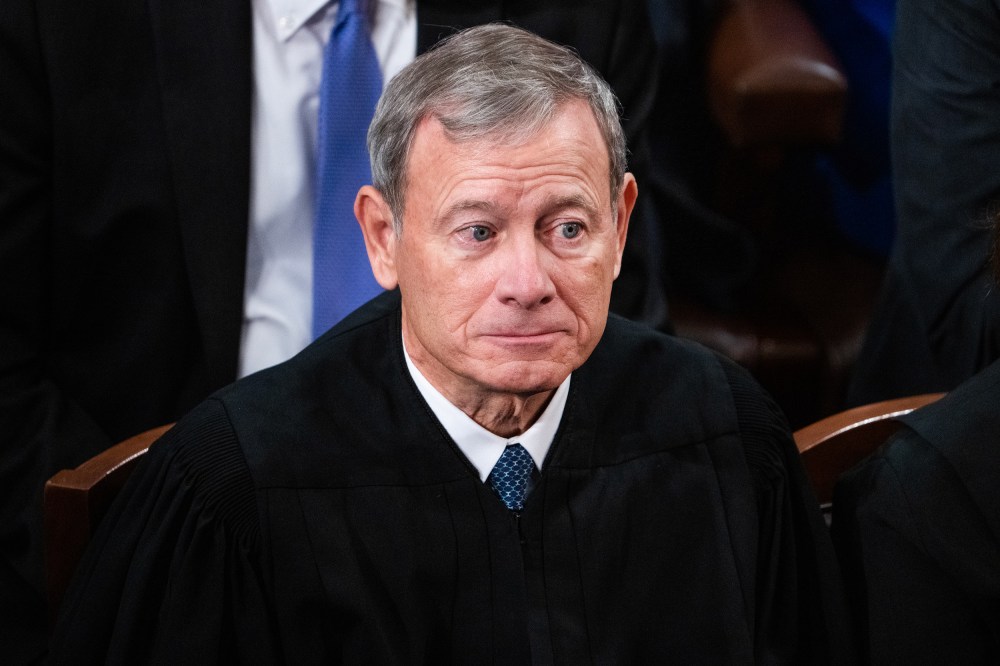

In Callais, Roberts has engineered the chance to take down Section 2.

In the 1980 case City of Mobile v. Bolden, the Supreme Court said Black voters could only have a case if they could prove that the at-large voting system was adopted intentionally to hurt minority voters. Even when the discriminatory effect was undeniable, though, the intent standard proved too difficult to meet, especially in places like Mobile that adopted their system before Black people could vote.