During the height of the racial justice protests that came after Minneapolis police murdered George Floyd, McDonald’s joined the fray of businesses and institutions declaring their solidarity with all those committed to ending racism. In a post on June 3, 2020, on the platform then known as Twitter, McDonald’s shared a short video listing Floyd’s name alongside other Black victims of violence, including Trayvon Martin and Atatiana Jefferson.

McDonald’s announced this week that it’s stepping away from its previously established DEI goals.

In muted red and yellow tones, the video read: “He was one of us; she was one us,” and continued that the “entire McDonald’s family grieves.” McDonald’s declared itself in solidarity with “victims of systemic oppression,” and made it clear that the corporation stands “with Black communities.” It offered as proof its donations to the Urban League and the NAACP. The video ended with a black screen with white letters: “Black lives matter.”

It’s unlikely that McDonald’s will be posting a similar video anytime soon. McDonald’s announced this week that it’s stepping away from some of its previously established DEI goals, retiring a specific DEI pledge and changing the way it refers to its diversity team.

The gestures made during the summer of 2020 appear to have been compelled more by peer pressure than by principle. Now, leaders of organizations from big-box stores to universities have publicly disavowed policies promoting diversity, equity and inclusion, whose acronym DEI has become shorthand for any and all attempts to address centuries of homogeneity, inequality and exclusion in educational and professional spaces.

In other sectors, leadership and development support programs for racial and ethnic minorities have been renamed, restructured or simply retired. And in light of the Supreme Court curtailing affirmative action in higher education and a concerted conservative onslaught on diversity, equity and inclusion efforts, McDonald’s frames its move as an attempt to pre-empt further court challenges to its diversity efforts.

In a Jan. 6 open letter to employees and franchisees that acknowledges “the shifting legal landscape,” the company’s senior leadership team announced what it called “a new concept: the power of OUR ‘Golden Rule’ — treating everyone with dignity, fairness and respect, always.” The company says it is:

- “retiring setting aspirational representation goals and instead keeping our focus on continuing to embed inclusion practices that grow our business into our everyday process and operations”

- “pausing external surveys to focus on the work we are doing internally to grow the business”

- “retiring Supply Chain’s Mutual Commitment to DEI pledge in favor of a more integrated discussion with suppliers about inclusion”

- and “evolving how we refer to our diversity team, which will now be the Global Inclusion Team.”

McDonald’s senior leadership said it remains committed to inclusion and believes a diverse workforce is a competitive advantage.

How it distributes its supply contracts not only impacts which companies get the opportunity to stock McDonald’s restaurants with hamburger buns and sausage patties, but it also impacts workers who prepare these essential goods. “Pausing external surveys” means aggrieved employees may have trouble collecting data and information on potentially discriminatory action within the organization.

McDonald’s is among a few corporations that have profited heartily from the idea that they are a friend to Black communities. Long before the summer of 2020, the summer of 1968 (which followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.) spurred soul-searching and reflection about how people in power could be vehicles for social change. Unfortunately, in both eras, many of the proposed solutions pivoted on businesses making commitments to recruit more talent of color while also eyeing the ways that these seemingly pro-social policies could also yield more profits.

McDonald’s has profited heartily from the idea that it is a friend to Black communities.

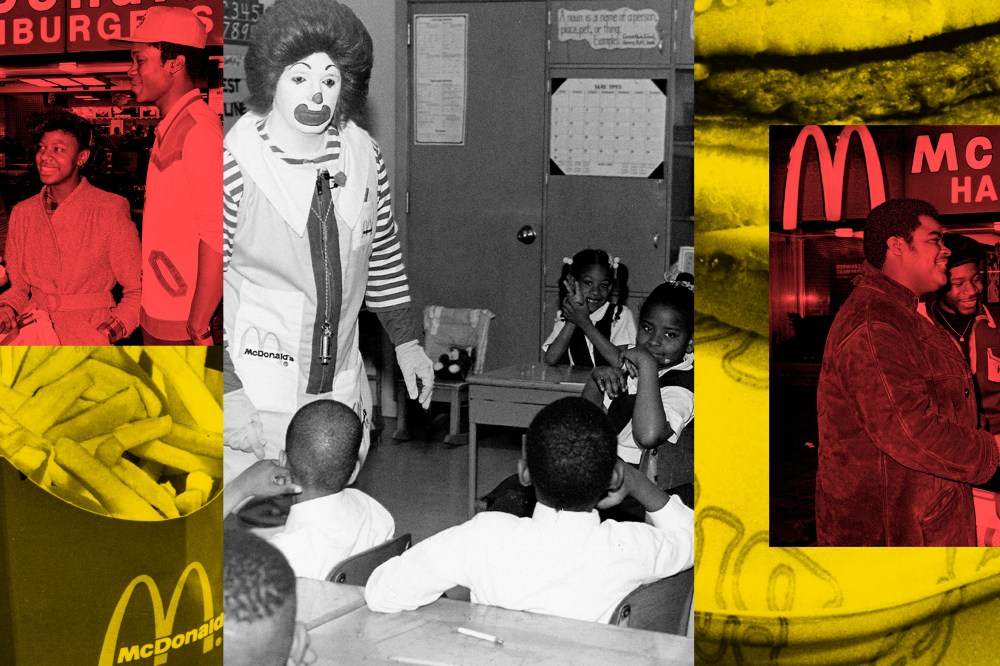

McDonald’s had already emerged as a dominant presence in the fast-food world, but in the late 1960s, the company would distinguish itself as leader in what would eventually be called DEI. The first step was recruiting its first Black franchisee, Herman Petty, to reopen a store on Chicago’s South Side in December 1968, and enlisting Black regional managers and advisers to build what would be called “Black stores.” A numerically modest but economically impactful group of Black franchise owners introduced and revived the brand among urban consumers of color. McDonald’s devoted an advertising budget to create content exclusively for minority media and recruited Black celebrities like Michael Jordan and Gladys Knight for national campaigns, making the company a leading source of contracts for Black-owned radio and TV networks, as well as marketing and consulting firms.

The McDonald’s logo appeared on material heralding contributions to civil rights organizations, historically Black colleges and universities and cultural initiatives. Many of those actions were initiated and funded by its growing network of Black franchise owners, who tried to hold McDonald’s accountable for contributing to a loyal and critical part of their consumer market.