After several weeks, the first seditious conspiracy case federal prosecutors have brought in a decade will soon be in the hands of the jury. Five members of the Oath Keepers organization are charged with seditious conspiracy and several other felonies, all centering around the group’s efforts to violently interfere in the Jan. 6, 2021, congressional certification of Joe Biden’s election win. Although the government’s evidence is strong, the case is not without its challenges. But the decision of the lead defendant and founder of the Oath Keepers, Stewart Rhodes, to testify in his own defense may actually have made the prosecution’s case even stronger.

The FBI investigation produced several thousand written communications among the organization’s members before, during and after the attack on the U.S. Capitol. These messages — texts, emails, Signal group chats, Facebook posts, etc. — can be an evidentiary bonanza, but they also present significant tactical challenges for the government. Prosecutors can’t just hand the jury a thousand written messages to read during deliberations. They must decide which messages are of sufficient evidentiary value to present to the jury. Then, each message must be introduced into evidence and read to the jury, generally during the testimony of an FBI agent.

Given this mountain of communications, the prosecutors did a fairly good job of keeping the testimony moving and the jurors engaged. Still, having sat through the testimony, I can attest that it was an unavoidably tedious process for everyone in the courtroom.

Even more compelling were the multiple exhibits of video and audio recordings. During testimony from U.S. Capitol Police Officer Harry Dunn, jurors saw video footage of several Oath Keepers who had unlawfully entered the Capitol standing within arm’s reach of Dunn as he guarded the entrance to a stairwell that led to Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office. As he faced off with the crowd, he yelled at them, “We have dozens of officers down, we’re taking them out on stretchers, you all are f—ing us up!” As they approached, Dunn stood firm and told them, “I’m not letting you come this way.” And they didn’t. Harry Dunn, as but one man, held that line. His testimony reinforces the fact that we have heroic public servants among us.

Not only did video capture the Oath Keepers moving in a military stack formation through the crowd before entering the Capitol, but some of the defendants were caught uttering deeply incriminating statements. One, Jessica Watkins, bragged that “we stormed the Capitol, pushed our way into the Senate and the House.” Another, Kelly Meggs, admitted to “looking for Pelosi” in the Capitol. Caldwell is caught saying, “Let’s take the damn Capitol. Let’s storm the place and hang the traitors.”

But the prosecution is not without its challenges, as can be seen from the testimony of a former Oath Keeper named Graydon Young. Last year, Young pleaded guilty to conspiracy and obstruction of Congress and agreed to testify against the defendants. Young went to the Capitol on Jan. 6 believing he was going to be “part of something historic.” He said the Oath Keepers’ goal was to “make contact with and disrupt Congress where they were meeting.” After the attack, he posted on Facebook that “we stormed and got inside.”

But when defense attorneys cross-examined Young, he admitted that there “was no express agreement to attack the Capitol.” Moreover, he conceded that neither Rhodes nor other Oath Keepers ever expressly said the plan or goal was to stop Congress from certifying the election results. On re-direct examination by the prosecutors, Young did affirm that there “was an implied agreement to stop the certification.” But in order to convict someone of any conspiracy, the prosecutors must prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that two or more people agreed to commit a crime and then at least one member of the conspiracy took one step toward the commission of that crime — what the law refers to as an overt act. So when one of the conspirators testifies that here was no express agreement, it gives the defense attorneys substantial ammunition for their closing arguments.

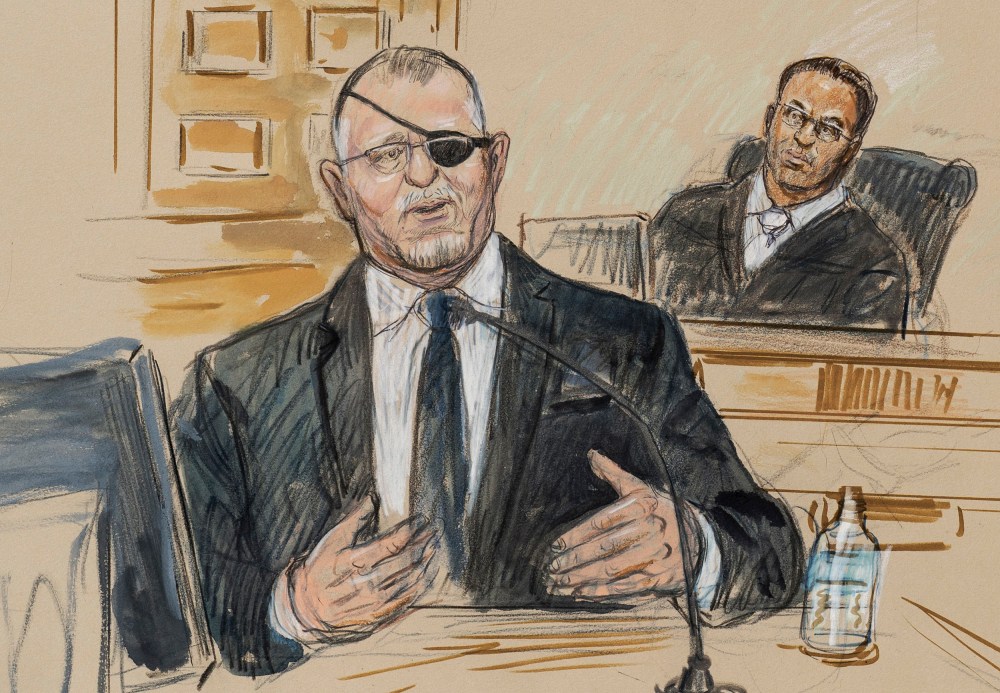

But the defense team likely wasn’t so pleased with another dramatic moment, when Rhodes took the stand to testify in his own defense. In my 30 years as a prosecutor, I can attest to the fact that defendants rarely take the stand at trial. Defense attorneys generally are content to rely on the high burden of proof to convict — beyond a reasonable doubt. A defendant has no burden of proof at trial and need not present any evidence whatsoever. But when a defendant chooses to testify, it’s often the highlight of the trial.