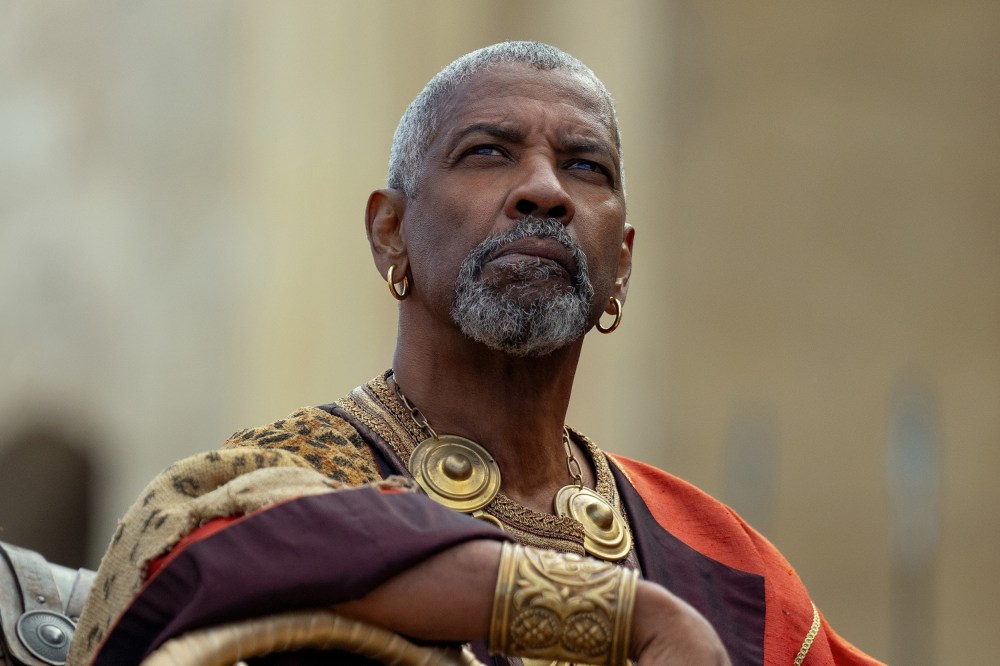

Denzel Washington, who steals the show in “Gladiator II” with his depiction of Macrinus, a gladiator-turned-arms and slave trader with political aspirations, has always been at his best when he’s playing characters who wrestle with moral questions and personal shortcomings. We’ve seen it in movies like “He Got Game” (1998), “Malcolm X” (1992), “The Hurricane” (1999) and “Fences” (2016). He won the Oscar for best actor for playing the equally righteous and sadistic LAPD Detective Alonzo Harris in “Training Day” (2001). Throughout a career spanning 50 movies, Washington shines in roles like Macrinus, in which he makes it hard for viewers to figure out whether he’s a “good guy” we’re supposed to be cheering or a “bad guy” we’re supposed to condemn.

Washington shines in roles like Macrinus, in which he makes it hard for viewers to figure out whether he’s a “good guy” we’re supposed to be cheering or a “bad guy” we’re supposed to condemn.

Perhaps he’s drawn to these roles because he knows that when he was growing up in Mount Vernon, New York, it would have been hard for people who saw him to figure out whether he was a “good guy” or “bad guy,” a “hero” or a “villain.” Washington describes for Ryan D’Agostino at Esquire a story of his life that includes sweet boyhood experiences like playing live music with friends, mimicking the walks of older neighborhood boys and excitedly watching the construction of a Boys Club (now a Boys & Girls Club) and then joining it. But there are darker moments, too, like running for shelter when a friend’s brother is about to commit a murder and Washington’s dealing drugs and shooting up himself.

Despite testing well in school, Washington tells D’Agostino, “I had one foot in the streets. I can’t remember if I was already selling drugs at that point. (Yeahhh, well … sometimes you do what you’re around.)” Then, referring to his friends who would eventually serve decades in prison, Washington says: “I was doing everything Frank and Mitch were doing. Throwing rocks at the penitentiary, as they call it. I was throwing rocks at the penitentiary at thirteen. I stopped going to school much, so they sat down with my mother, said, Look, you need to get him out. Said I showed ‘potential.’”

Washington’s first-person account of his childhood is reminiscent of James Baldwin’s “Letter From a Region of My Mind,” in which he describes fearing a future life of crime that he could see more clearly than any other.

Things could have spiraled for Washington like they did for his closest friends if his mother hadn’t sent him away to what he calls “a little private, semi-military school” in upstate New York. One of the biggest takeaways from Washington’s interview is that there is more to him than meets the eye. He plays heroes but insists he isn’t one. It follows, then, that he can play bad guys convincingly but he’s not a bad guy — even if he’s done things that would get him labeled as bad throughout his life.

As Macrinus, Washington delivers his lines and flashes that smile as only he can, playing a character who we know from the beginning is sketchy. But Macrinus’ disdain for the bloodthirsty regime that held him as a slave is somewhat noble. In portraying the villain with redeeming qualities, Washington blurs the line between what counts as virtue and what counts as vice. Again, Washington excels at portraying these sorts of characters who cannot be painted with too broad a stroke, ones who are basically honorable but fall short or ones who are mostly bad but show flashes of heroism. “Even in the darkest stories,” he told the magazine, “I’m looking for the light.”