As a Black Southerner and the son and grandson of Jim Crow survivors, my life exists in the shadow of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the Supreme Court decision that turns 70 years old on May 17. From growing up in a racially integrated neighborhood to attending schools that the law wouldn’t have let my parents attend, there’s nothing about my life that was not affected by Brown. It’s not lost on me that I write these words from my office on the campus of the University of Kansas. It’s not far from where Linda Carol Brown, because she was Black, was made to walk past the all-white Sumner Elementary School to catch the bus to Monroe Elementary School, which was all Black.

Linda Carol Brown, because she was Black, was made to walk past the all-white Sumner Elementary School to catch the bus to Monroe Elementary School, which was all Black.

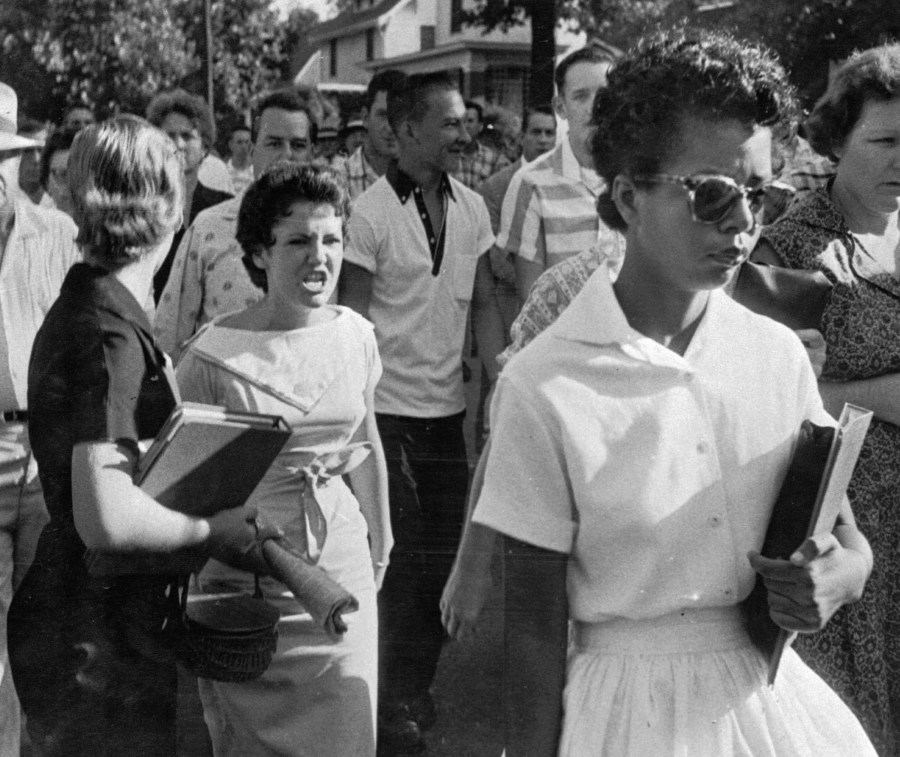

But one of the hard facts that we must confront is that in the 70 years since Brown, the social and legal resistance to desegregation has never stopped. Segregationists employed a variety of tactics whose legacies have made American education an enterprise that’s endemically segregated by race and class today. Whether it’s the all-white private schools that were created in response to Brown, the white flight out of cities that was inspired by the same ruling, a subsequent Supreme Court ruling that there’s no right to an equally funded education, or the growing popularity of publicly funded vouchers for private schools, the promise of the 1954 decision hasn’t translated into reality for today’s Linda Carol Browns.

According to a 2022 report from the Government Accountability Office, “During the 2020-21 school year, more than a third of students (about 18.5 million) attended schools where 75% or more students were of a single race or ethnicity” and “14 percent of students attended schools where 90 percent or more of the students were of a single race/ethnicity.” I will return to these legacies shortly, but it is important to unpack how Chief Justice Earl Warren’s court, which overturned the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, justified its Brown ruling.

It used the 14th Amendment to find that segregated schools were unconstitutional even if such schools were of equal quality. (Of course, that would have been a rare occurrence, due in part to the Supreme Court’s 1899 ruling in Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education that allowed Black people’s tax dollars to be used to fund schools only white people could attend.) For Black students, Warren wrote in the unanimous decision, segregation “generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. … The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group.”

Some assert that Black students don’t need to be in the same room as white students to learn. Of course, this is true, but it’s also irrelevant to the importance of Brown ending legal segregation. The deranged logic of Plessy v. Ferguson upheld the Jim Crow racial caste system, and rejecting that deranged logic was the point of the ruling. To invoke Justice John Marshall Harlan’s extraordinary dissent in Plessy, “But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here.” To be segregated by law, to paraphrase constitutional law scholar Laurence Tribe, is to be labeled as inferior by the state.

All arguments against this obvious truth are variations of the nonsense in the Plessy decision that segregation is only “a badge of inferiority” because “the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.”

As for the legacies of resistance to integration, a preferred tactic of segregationists was to found so-called segregation academies, private schools that were whites-only, until the Supreme Court ruled that private schools could not discriminate on the basis of race in Runyon v. McCray in 1976, 22 years after the Brown decision. Many secular and religious private schools still operating today were founded as segregation academies.

Voucher programs like the ones in Georgia, Louisiana and Washington, D.C., may serve diverse student populations now, but public vouchers to attend private schools began as a scheme to keep white children and children of color in segregated schools because private schools could racially discriminate until 1976.