I was around 8 years old the first time I can remember seeing Jacob Lawrence’s work. My mother had a print of his, “The Lovers,” hanging on her bedroom wall. The colors are what I remember most. The yellow walls. The red end table. The green sofa with the bright blue record player sitting on top. And two dark, beautifully brown lovers entangled in each other’s arms. I couldn’t walk by her room without slowing to take a peek.

Over the years I learned to spot Lawrence’s work on sight. His color palette. His subjects. His use of angles and sight lines and all the energy conjured in his brushstrokes. But there’s also something so accessible about his work.

Over the years I learned to spot Lawrence’s work on sight. His color palette. His subjects. His use of angles and sight lines and all the energy conjured in his brush strokes.

I hadn’t seen his paintings hanging behind velvet rope in some sterile old museum where people who look like us are often an afterthought. I saw inexpensive reprints hanging on the walls of working-class Black families’ homes and on calendars you might get for Christmas and in coffee table books you’d find at a neighborhood Black bookstore.

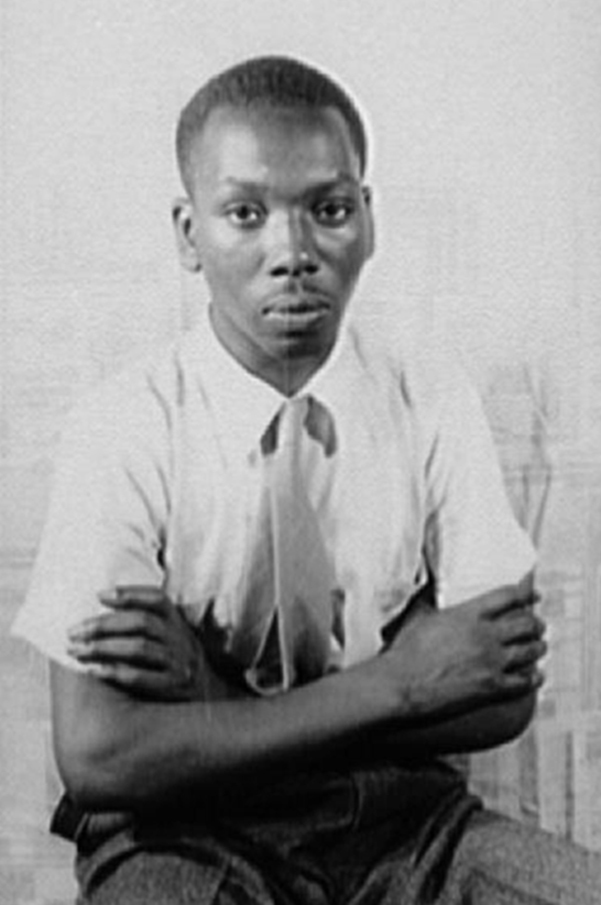

Jacob Lawrence felt like ours. I’d grow to not just appreciate but also understand what I think Lawrence was after. He wanted us to know that we were seen. There was such familiarity in so many of his pieces. He made ordinary Black builders and Black families seem extraordinary in the very being. He made our Black heroes look something just like us.

Few artists dead or alive have captured the essence of Blackness in America quite like Lawrence. It’s not just that his subjects were mostly Black or how deftly he used a brush and canvas to illustrate the Black experience in America, although both of those things are true. His power was in creating a visual language that helped shape how America saw Black people and how Black people saw themselves.

He rose to acclaim first in Harlem, New York, the Black mecca. His patrons were teachers and laborers and neighbors — the salt of Black New York. This was in the late 1930s into the early ’40s, years before what many consider the modern civil rights era. Black folks were still being lynched across America, and images of Black people in the arts, the media and pop culture were largely derogatory or missing altogether.

But Lawrence centered Black life in a way that bucked the impulse of many of his African American contemporaries who created a diminished kind of Black art that was more appeasing to the white gaze.

He famously illustrated the critically acclaimed, 60-piece series called “The Migration” in 1940, which depicted the mass movement of millions of African Americans from the Jim Crow South to Northern cities during a stretch of the early to the mid-20th century.

The exodus is known as The Great Migration. The migrants left the violence of Southern soil for the hope of better days and opportunities in the North, pouring into cities like Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia and New York. These cities, like their new transplanted inhabitants, would forever be changed. From politics to law, arts to entertainment, America was shifting under the feet of Black Americans.

And Lawrence not only captured this moment, but he also centered the Black experience in telling the broader American experience.

As I got older and my collection of books and art and ephemera grew in quantity and value, I dreamed of one day getting my hands on an original Lawrence print. While there was something accessible about the images he created, which were almost ubiquities in certain Black spaces, original signed and numbered prints were much more elusive and more valuable. I’d keep my eyes peeled at antique shops and art houses and in the online auctions I’m kind of addicted to.

And then one day not long ago, I finally found it. I found my Lawrence.