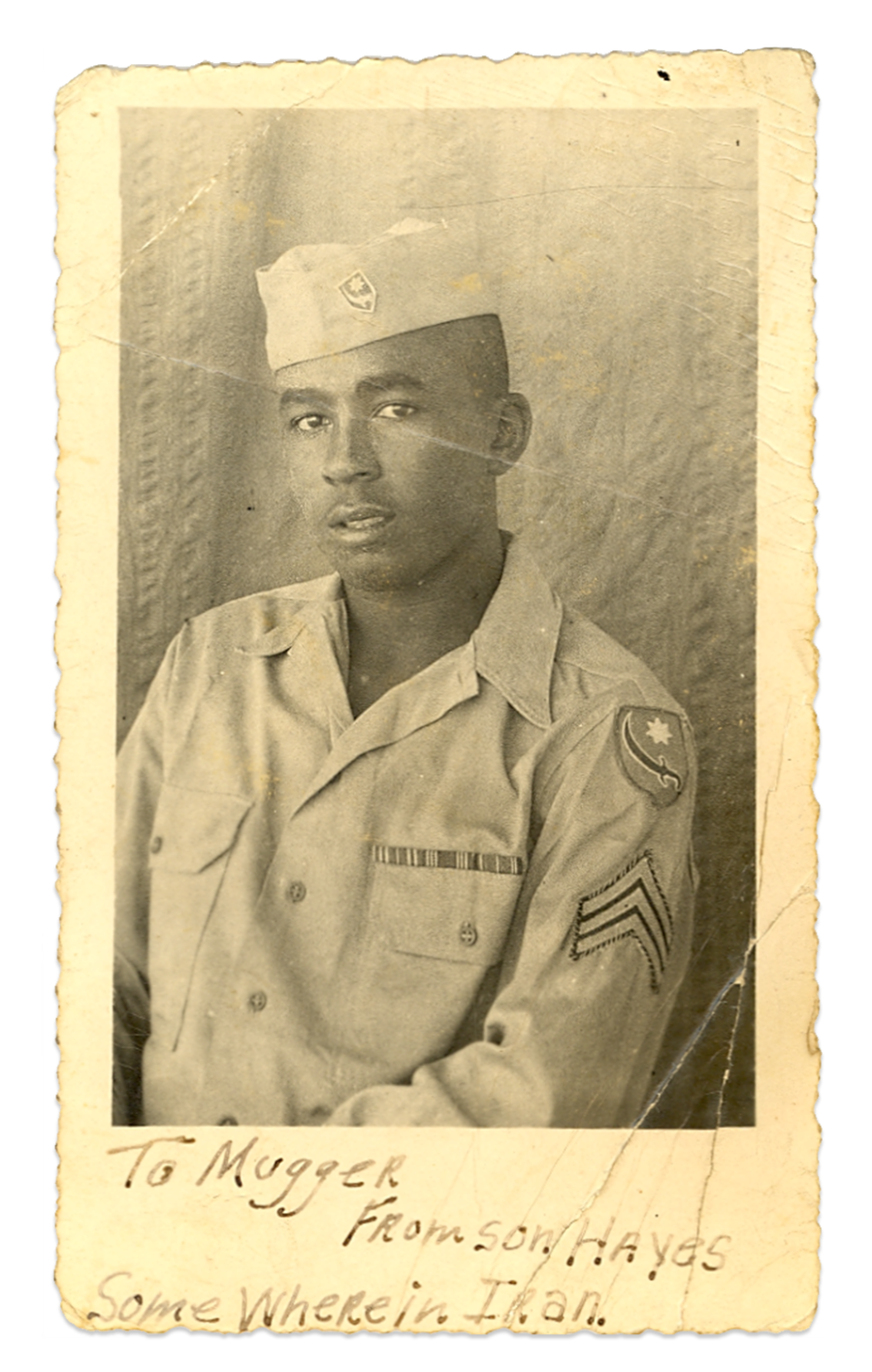

Approximately 1.2 million Black Americans served in the military during World War II. My grandfather, for whom I’m named, was one of them.

When he and his fellow soldiers returned home, they were greeted with a chance for success previous generations of veterans had been denied. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 — better known as the GI Bill of Rights — offered them four years of college tuition and cheap low interest, zero-down-payment home loans as gratitude for their service.

While on paper the benefits were for everyone who had served, in practice things were very different, as most things were at that time.

While on paper the benefits were for everyone who had served, in practice things were very different, as most things were at that time. Black veterans were blocked from tapping into the full scope of the GI Bill’s programs, an injustice that helped widen economic and educational disparities among former service members along racial lines. Now over 75 years later, Democrats in Congress want to redress that historic injustice.

Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., and Rep. Seth Moulton, D-Mass., introduced the GI Bill Restoration Act Thursday to coincide with Veterans Day. Sen. Raphael Warnock, D-Ga., is expected to introduce the bill in the Senate. If passed, it would extend access to the VA Home Loan Guaranty Program and the Post-911 GI Bill’s education benefits to the surviving spouse and/or certain direct descendants of Black WWII veterans.

My grandfather, Hayes S. Brown, was drafted into the Army in 1943. He served three years, mostly in Iran as a military police officer. He was honorably discharged as a technician in 1946, two years after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the GI Bill into law. But he returned to his hometown of Manassas, Virginia, with Jim Crow still in full swing.

The GI Bill encouraged loans for new houses over existing housing, prompting the surge of new suburbs and an upswing in construction. The first two years after the war ended, 40 percent of mortgages issued were guaranteed by the Veterans Administration. By 1955, the VA was backing “close to a third of housing starts,” Cornell University’s Suzanne Mettler found.

But this was also a time when redlining, a government-sanctioned exclusion of Black residents from white neighborhoods, was in full effect. The federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation’s appraisers “penalized neighborhoods with a strong Black presence, assigning them the lowest rating of D, indicating that the residents were considered a risk for mortgage loans,” MSNBC columnist Keisha N. Blain wrote in September. “This made it extraordinarily difficult for them to receive federal housing assistance.”

A decade after leaving the service, and years after my father and his older brother were born, my grandfather was finally able to purchase a house in Washington, D.C. That house on East Capitol Street was in the city’s northeast, close to the border with Maryland. That corner of the district was an enclave of nonwhite residents at a time when the racial covenants that had barred Blacks from buying homes in some of the posher areas of the city had just been overturned.