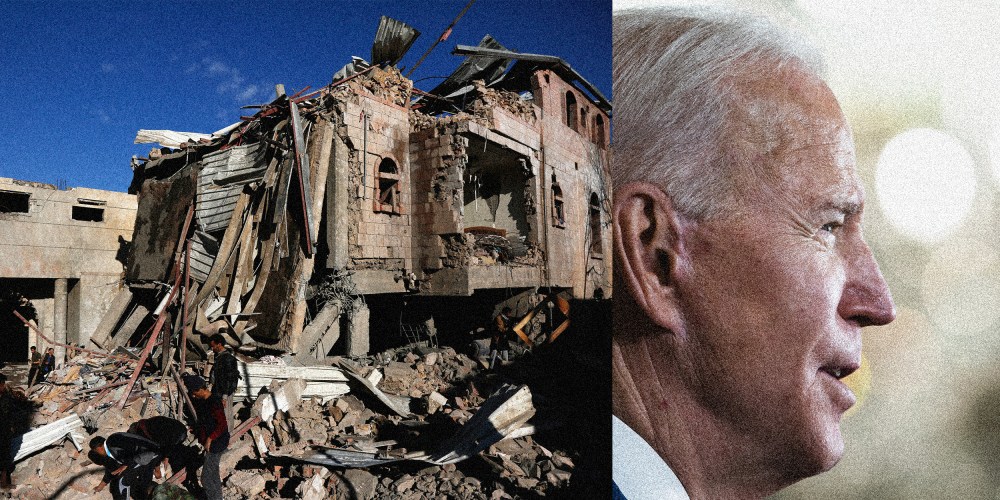

When Yemeni Houthi rebels struck Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, killing three people on Jan. 17, the Biden administration strongly condemned what it called “terrorist attacks.” It was the 14th time the State Department had condemned the Houthis since President Joe Biden entered the White House.

In many ways, this unquestioning support for the Saudi dictatorship is unremarkable.

Yet, days later, when Saudi Arabian airstrikes killed at least 70 civilians in Yemen, including three children, the Biden team only mustered a meek call for all parties to de-escalate. Despite the carnage, Biden sustained his perfect record of never condemning Saudi Arabia for its devastation of Yemen, let alone calling it terrorism. It’s time for Biden to make a real break with past U.S. policy by ceasing to take sides in other countries’ conflicts.

In many ways, this unquestioning support for the Saudi dictatorship is unremarkable. Former President Donald Trump coddled the notorious Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and even refused to slap him on the wrist after his intelligence operatives kidnapped and beheaded Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi. As president, Barack Obama had a contentious relationship with then-Saudi King Abdullah, yet it was Obama who greenlighted Saudi Arabia’s war against Yemen in the first place. And the Bush family was so close to the Saudi royal family that Riyadh’s longtime ambassador to Washington, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, was nicknamed “Bandar Bush.”

Biden himself created the expectation that his presidency would see an end to business as usual with the Saudi dictatorship. In his first major foreign policy speech, in February, he declared that “the war in Yemen must end.” During the presidential debates in 2020, he pledged to make the Saudis “pay the price and make them in fact the pariah that they are.”

Saudi Arabia has yet to pay a price for its destabilizing activities — the U.S. just sold the crown prince $650 million worth of advanced American weaponry — nor has Biden treated the Saudi government as “the pariah that they are.”

Biden’s Middle East point person at the White House, Brett McGurk, may have provided a hint as to why we’re witnessing this disheartening return to business as usual when he toured the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf in November and told the Emirati paper The National that Biden has adopted a strategy of “going back to basics.” This was in reaction to the overly ambitious policies of the three past administrations. There would be no more attempts to transform the Middle East or overthrow nonpliant governments. Based on “hard lessons learnt,” McGurk said Biden would instead focus on “the basics of building, maintaining and strengthening our partnerships and alliances,” which he hailed as a “unique comparative advantage.”

A closer look reveals that these destabilizing objectives are nothing more than logical outgrowths of the very same “basic” Middle East policies Biden seeks to “return” to.

On the face of it, it’s hard not to rejoice over the discarding of regime-change policies and fanciful imperial fantasies about transforming the Middle East. But a closer look reveals that these destabilizing objectives are nothing more than logical outgrowths of the very same “basic” Middle East policies Biden seeks to “return” to.

At its core, U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East since the end of the Cold War has been hegemonic. The United States has sought to dominate the region militarily while citing an expansive list of interests to justify the obsession with this region: from protecting the safe extraction of the region’s energy resources to preventing adversaries from establishing hegemony there, disrupting terrorist threats to Americans and U.S. partners, preventing the regional proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, encouraging bilateral trade and economic prosperity, and, perhaps most expansively, protecting and standing by U.S. “allies.”

Of these interests, supporting U.S. allies is a leading reason why the Middle East has become the epicenter of American overreach and the unwarranted taking of sides in local conflicts. We have essentially treated the often ill-defined and aggressive objectives of U.S. partners in the region (none of whom are treaty allies of the United States even though they are often referred to as such) as our own, essentially letting these mostly autocratic dictatorships determine U.S. policy in the Middle East.

If U.S. foreign policy is centered on “strengthening our partnerships and alliances,” as McGurk suggested, rather than U.S. interest rigorously defined, then not only will it manifest itself in regime change in states that pose a threat to those partners, but it will also continue to entangle America in a variety of regional conflicts that are at most marginal to U.S. security. Instead of the U.S. contributing to regional stability and helping resolve conflicts, this expansive definition of U.S. interest makes America take sides in and become a party to Middle East wars — of which the vast majority do not matter to the United States.

Yemen is a case in point. Few in America know who the Houthis are, let alone understand why they purportedly pose a threat to the United States. Yet fewer can articulate how the outcome of the conflict between the Houthis and the Saudi-backed government matters to the United States, let alone warrants American involvement in that war. In fact, before the war, the United States viewed the Houthis as an ally against a group that did pose a threat to the American heartland: the Al Qaeda terror network. But the logic of standing by America’s “ally” Saudi Arabia prompted the United States to set aside its own interest and follow the lead — and take the side of — the luminaries in the House of Saud.