New York Times columnist Tom Friedman is pretty sure he’s found the cure for America’s rampant polarization. We need only take our cue from Israeli politics and put a Democrat and Republican together on the same ticket in 2024. Unfortunately, this has been tried before — and it wound up being a mess that led to the country’s first presidential impeachment.

After multiple Israeli elections failed to produce a stable government, Friedman explained, an unlikely coalition came together to form a four-year unity government:

It’s the most diverse national unity government in Israel’s history, one that stretches from Jewish settlers on the right all the way to an Israeli-Arab Islamist party and super-liberals on the left. Most important, it’s holding together, getting stuff done and muting the hyperpolarization that was making Israel ungovernable. Is that what America needs in 2024 — a ticket of Joe Biden and Liz Cheney? Or Joe Biden and Lisa Murkowski, or Kamala Harris and Mitt Romney, or Stacey Abrams and Liz Cheney, or Amy Klobuchar and Liz Cheney? Or any other such combination.

Let’s for now leave aside the very real differences between Israel’s parliamentary, multiparty government system and our own two-party presidential way of doing things. History shows that Friedman’s idea is one that gets constantly recycled but never pans out.

History shows that Friedman’s idea is one that gets constantly recycled but never pans out.

Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., in 2004 shot down overtures to serve as running mate to fellow Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass. Pundits floated the idea of McCain picking a Democrat as his vice president four years later, before he went with conservative Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin instead. Former Govs. John Kasich and John Hickenlooper — a Republican from Ohio and Democrat from Colorado, respectively — were pitched as a plausible unity ticket in 2020, despite seemingly zero demand from the electorate.

And in 2011, Friedman himself was trumpeting the work of Americans Elect, a group that wanted “to take a presidential nominating process now monopolized by the Republican and Democratic parties, which are beholden to their special interests, and blow it wide open.” (It did not.)

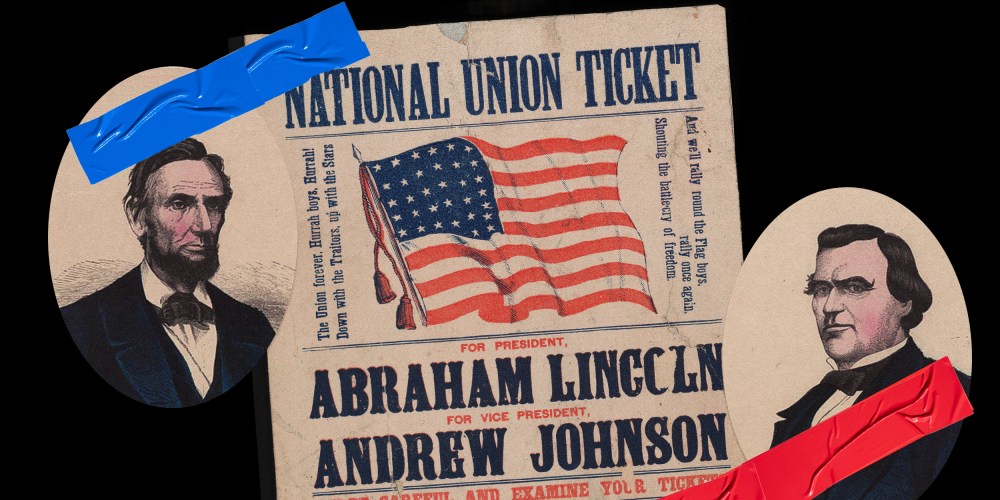

To Friedman’s credit, there is a precedent. There was a time when candidates from separate parties formed a single ticket. Abraham Lincoln, who became our first Republican president when he took office in 1861, won his second term as a candidate on the National Union Party ticket. In the process, he ditched his first vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, for Democrat Andrew Johnson of Tennessee.

Lincoln’s prospects for re-election in 1864 were not exactly great. The Civil War was dragging on, Union victories were few and far between and Lincoln faced an internal challenge from the left from the so-called Radical Republicans. Hamlin, a Maine Republican, was not super enthusiastic about serving again and was unlikely to have helped Lincoln in his bid to be the first second-term president since Andrew Jackson.

On the other hand, Johnson was a War Democrat, a firm believer in the preservation of the union. Hailing from eastern Tennessee, which was pro-Union, he was the only senator from a state that had joined the Confederacy to not resign his seat. When the Union Army occupied Tennessee, Lincoln had appointed him as military governor. He was also anti-slavery and, altogether, a potential boon politically for Lincoln.

While historians dispute whether Lincoln nudged the convention to pick Johnson, the outcome was clear: The pair won handily, both in the Electoral College and the popular vote. Political polling had yet to be developed, so it’s hard to know how much of a swing adding Johnson to the ticket provided. Historian Michael Burlingame argued, though, that having Johnson on the ballot meant “thousands of moderate Democrats in the border states moved into the Lincoln column.”

Friedman and others who’d propose someone like Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., as President Joe Biden’s 2024 running mate are hoping she’d do something similar: bring in moderate, suburban Republicans who swung away from former President Donald Trump 2020. (They don’t say, though, why they think those voters would swing back to Trump in 2024, but I digress.) In this way, the partisan divide Trump has inspired could be healed and the antidemocratic forces he’s marshaled turned back.

It’s a lovely bipartisan vision — but to see why that would be a mistake, look past the 1864 election and to what came next. While it’s taboo to discuss, the main job of the vice president is to act as a successor if the president is unable to fulfill the role. Johnson ascended to the presidency following Lincoln’s assassination, just one month after their term began. Johnson was left to manage the aftermath of the Civil War on his own terms.