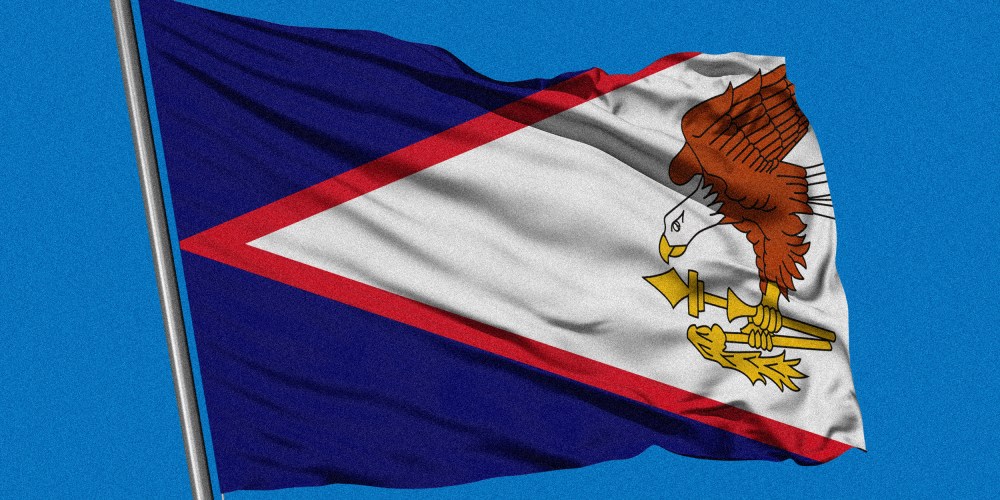

The principle that anyone born in the United States is an American citizen is enshrined in the 14th Amendment. But in a divided decision Tuesday, a federal appeals court reaffirmed the unique inapplicability of the citizenship clause to one of America’s six federal territories— American Samoa, the only one of the six where birthright citizenship does not currently apply.

The ruling in Fitisemanu v. United States doesn’t just rest on a deeply flawed understanding of the 14th Amendment. It also breathes new life into a long since discredited distinction that the Supreme Court drew in the early 20th century — one in which territories that just happened to be predominantly white received full constitutional protections, while those that were not … didn’t.

After years of struggle between the U.S., Germany, and United Kingdom for dominance over the Samoan island chain, the islands were partitioned into two in 1899. Just prior to the partition, America had gained significant overseas territories as a result of concessions arising out of the Spanish-American War. The eastern group of Samoan islands quickly joined the ranks after tribal leaders formally ceded the land to the Americans. The western group remained a German possession through Germany’s defeat in World War I, becoming an independent nation in 1962.

But even as residents of other U.S. territories gained birthright citizenship either by constitutional mandate or statute, and even as American Samoans (a disproportionate percentage of whom have served in the U.S. military throughout the past century) fought for similar and other protections in Congress, they were left out.

A federal judge in Utah had agreed that the denial of citizenship was unconstitutional — but a divided panel of the Denver-based federal appeals court reversed that decision.

In the case decided Tuesday, three American Samoans living in Utah had brought suit challenging their denial of citizenship — which, among other things, means that they are denied the right to vote, the right to run for elective federal or state office outside American Samoa, and the right to serve on federal and state juries. A federal judge in Utah had agreed that the denial of citizenship was unconstitutional — but a divided panel of the Denver-based federal appeals court reversed that decision.

Writing for the majority, Judge Carlos Lucero relied heavily on a series of early-20th century Supreme Court decisions known as the Insular Cases. In those cases (none of which dealt specifically with birthright citizenship), the justices adopted a distinction between “incorporated territories” (those U.S. possessions that were “destined for statehood”) and “unincorporated territories” (those U.S. possessions that were not). The Constitution generally applied to its fullest extent in the former, whereas courts were left to decide on a case-by-case (and provision-by-provision) basis the extent to which it applied in the latter.

Forests have been felled on the myriad problems with the Insular Cases. To make a long story shorter, as five of the leading scholars on the subject wrote in 2014:

The Insular Cases’ approach to the constitutional status of the U.S. territories lacks any grounding in constitutional text, structure, or history. The Insular Cases, rather, reflected the assumptions of the time that the United States, like the great European powers of that era, must (despite being constrained by a written Constitution) be capable of acquiring overseas possessions without admitting their ‘uncivilized” and “savage’ inhabitants of ‘alien races’ to equal citizenship. That reasoning, even if it were constitutionally relevant, is the product of another age. It has no place in modern jurisprudence even if … it had any validity in earlier times.

Of course, lower courts would still be bound by those decisions if any of them were squarely on point. But none of the Insular Cases involved the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment. Instead, the Court of Appeals was free to reach the issue anew in this case — and still chose to abide by the Insular Cases’ discredited framework. In the process, the court wholly ignored the original context of the citizenship clause — enacted to overturn a Supreme Court decision in which one of the questions had been the status of slaves in federal territories.

The Supreme Court’s 1857 decision in the Dred Scott case is infamous for its full-throated legal defense of the institution of slavery. But its constitutional significance was its specific holding that slaves and their descendants were not — and could not become — U.S. citizens. Congress accordingly did not just amend the Constitution to abolish slavery after the Civil War; it also wrote into our founding charter the principle of “birthright citizenship” — that anyone born in the United States is a citizen thereof.