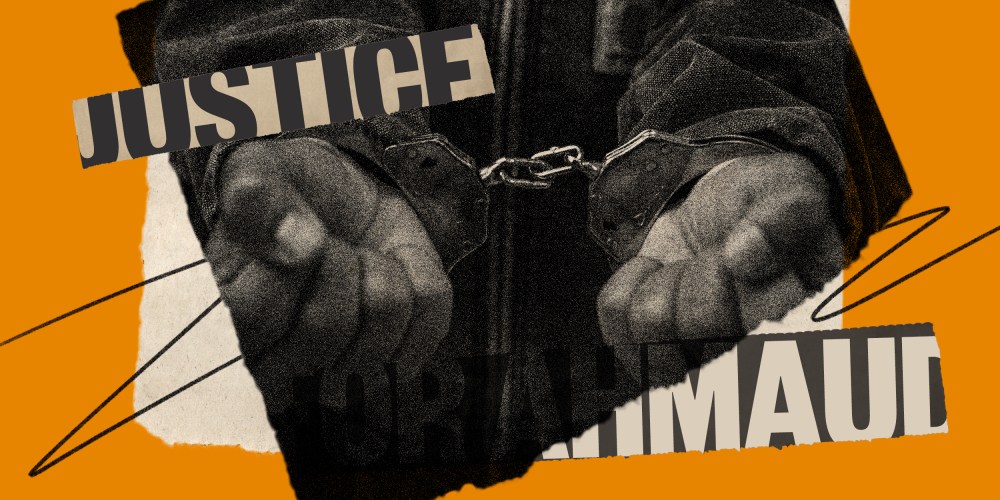

Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man jogging near Brunswick, Georgia, was shot and killed on Sunday, Feb. 23, 2020, after being pursued by three white men: Gregory McMichael, Travis McMichael, and William Bryan. The three men face a slew of charges, including malice murder, felony murder and aggravated assault. Jury selection is now underway in their trial.

The defendants appear to believe that their claim about making a citizen’s arrest exonerates them from the charge that they targeted Arbery because of his race.

The jury will be asked to decide if the men were right to try to detain Arbery in the first place. The defendants claim that they believed Arbery was connected to burglaries in the neighborhood and that they were conducting a citizen’s arrest. The McMichaels armed themselves and pursued Arbery in their vehicles. The first two prosecutors who investigated the case accepted the citizen’s arrest defense, including a prosecutor who was accused of showing favoritism to the defendants and later indicted on a misconduct charge. A special prosecutor is now in charge of the case.

The defendants appear to believe that their claim about making a citizen’s arrest exonerates them from the charge that they targeted Arbery because of his race.

Their attempts are futile, however, because in the United States, citizen’s arrest laws have a racist past. Georgia’s law was enacted in 1863, two years before the Civil War ended and when slavery was still legal in the state. The context surrounding the law’s emergence reveals much about its goals. It was introduced while Georgia was a Confederate state and most of its military was stationed in Virginia. As Joseph Margulies, professor of law and government at Cornell University, told NPR, the law was “basically a catching-fleeing-slave law.”

Citizen’s arrest laws have their roots in the European practice of private arrests, where citizens could detain someone they witnessed committing a crime. In Colonial America — before the establishment of police forces — they were a method of maintaining peace and safety. However, the spread of these laws in America coincided with the rise of slave patrols. Like the growth of law enforcement in the United States, we should not view citizen’s arrests as race neutral.

In rural areas, where the number of enslaved people often outnumbered the white population, slave patrols were formed to police the activities of the enslaved. The earliest slave patrols, formed in the Carolinas in the 1700s, set out to monitor the movement of the city’s enslaved population and prevent any uprisings. The citizen’s arrest laws were similarly designed to empower (white) private citizens to “protect” their communities.

“In theory,” Rashawn Ray, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, argues, “citizen’s arrest laws are laws that allow an ordinary person to see a criminal act occurring and be able to retain a person, to hold a person down, stop a person until law enforcement arrives.”

In practice, however, these laws are misused and ultimately lead to racial profiling. They have become a means by which private citizens can intervene simply because they deem another individual to be suspicious or doing something questionable — even if the act does not violate any laws. As was the case with Arbery, this has had deadly consequences.

Like the growth of law enforcement in the United States, we should not view citizen’s arrests as race neutral.

After the Civil War, Southern states crafted “Black Codes” that sought to control the recently freed population and encouraged law enforcement and white vigilante groups to use violence in the name of securing “law and order.” In the 19th and 20th centuries, this was most apparent when white mobs — sometimes with police cooperation — lynched Black men and women to enforce the racial hierarchy.