Edward Snowden’s continuing disclosures of sensitive information are no doubt infuriating the Obama Administration. In short order, the former National Security Agency contractor has revealed: a surveillance program that scooped up millions of records of Americans’ communications; PRISM, a program used by the NSA to access digital data through the servers of major Internet companies; the identities of civilian computer networks in Hong Kong and China targeted by the U.S.; and eavesdropping on foreign governments by the U.S. and the United Kingdom. The Department of Justice is reportedly preparing an indictment against him and will probably reach for its favored tool in leak cases: the Espionage Act. Characterizing Snowden’s actions as espionage is legally possible. But doing so may actually make it difficult for Hong Kong courts to send him back for trial.

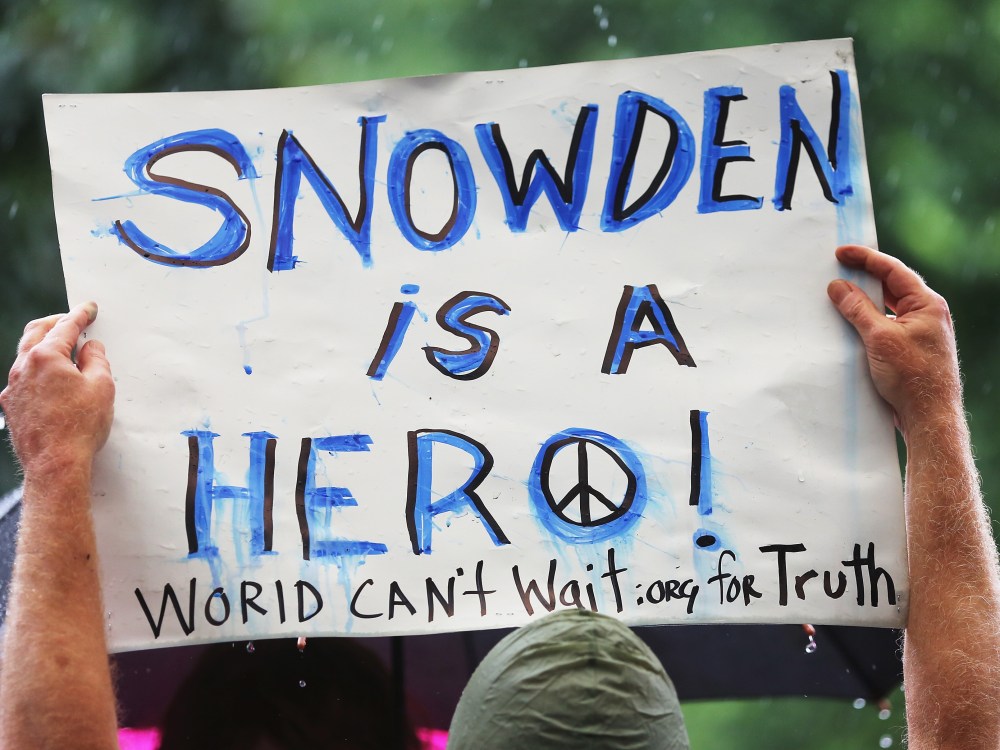

Those calling for Snowden’s head are convinced his disclosures harm national security. Others are more skeptical. Are terrorists going to change their behavior because they know about PRISM, or did they in any event presume that their communications were being monitored? Haven’t the Chinese always assumed that their civilian networks were being hacked, as they now say? Did diplomats really think that an Internet facility set up by the U.K. was free from spyware? Even as these issues are debated, Snowden continues to portray himself as a whistleblower for the world. He argues that his disclosures have brought no benefit to him, but will instead “help the public of the world, regardless of whether that public is American, European, or Asian.”

While these matters dominate the public discourse, they make no difference to the government’s ability to bring an Espionage Act prosecution. Recent whistleblowers have been charged under a section of the law that only requires the government to show that Snowden “willfully” communicated information to someone not authorized to receive it. At the urging of the Obama Administration, several courts have held that there is no requirement that the accused intended to cause harm to the United States or benefit another country. Nor is it necessary that the disclosures actually caused harm. It is enough if the accused had “reason to believe” that disclosures could injure the U.S. or aid a foreign nation.

But relying on the Espionage Act in Snowden’s case could backfire. The 1996 extradition treaty between the United States and Hong Kong contains an exception for political offenses, which Snowden will almost certainly invoke.