Sanford, Fla.— Jennifer Sherman, a grandmother of three from Atlanta, drove eight hours to be here. Cephus Johnson, whose nephew was killed by transit police in Oakland, flew all the way from California. And Noche Diaz, an anti-police-brutality activist from New York City, boarded a bus in Chinatown and spent the next 16 hours en route to Georgia before joining a group of friends for the 10-hour drive to Sanford.

“I was anxious, I was afraid, but I knew I had to be here for the start of this trial,” said Sherman, standing on the grass outside of the Seminole County Criminal Justice Center, where the trial of George Zimmerman for second-degree murder began on Monday morning with jury selection.

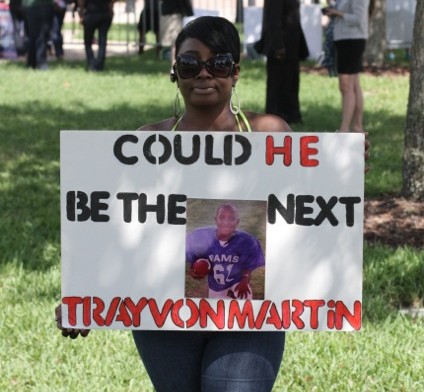

Sherman stood with a dozen or so other people who’d gathered in front of the courthouse, holding a large sign with a picture of her 9-year-old grandson Semaj that read, “Could He Be The Next Trayvon Martin.”

Trayvon Martin, 17, died just about six miles from the court house where scores of potential jurors were convened and questioned today.

Zimmerman, who has pleaded not guilty, says he shot Martin in self-defense after the teenager attacked him. When police initially declined to arrest Zimmerman, thousands of protestors descended upon Sanford. There were massive rallies with celebrity activists who compared Sanford to Selma and Montgomery. The case has remained controversial.

And yet the crowd outside the courthouse on Monday was small.

City officials have been preparing for the trial for about a year, creating so-called free speech zones for protestors, making accommodations for the national and international press figured to be in town for the trial, and assigning officers with the county sheriffs and police departments to guard the courthouse and other key locations in town. The planning so far has cost more than $500,000, according to City Manager Norton Bonaparte. But little of that exhaustive preparation seemed necessary Monday, as some of the protesters, many wearing hooded sweatshirts like the one Martin was wearing the night of his death, began trading their protest signs for places in the shade as the late-morning sun crept higher and hotter.

There was no chanting, no apparent rancor. There seemed to be just as many members of the media present as there were protestors. But the surprisingly sparse crowd did little to dim the spirit of those who’d trekked from across the country or from across town to be here.

“I said I would be here for the start of the trial and I made it,” said Sherman, who used four days of vacation from her job with AT&T. “I’m here to support Trayvon Martin and his family. It’s not just his family that was hurt by this. We’ve all spent a year and a half being mad, being sad and being angry. I’m here for justice.”

Cephus Johnson, the uncle of Oscar Grant, 22, who was shot and killed by a Bay Area transit officer on New Year’s Day in 2009, said he made the trek from Oakland to carry the spirit of all the young, unarmed black and brown men killed by law enforcement, security guards and others each year.

“When we heard about Trayvon it hit us hard. It was painful, gut-wrenching, and we knew exactly what his family was going through,” said Johnson. “We couldn’t have made it without the support of the community, coming to court with us, helping us to get through the process. So that’s why we’re here.”

Grant’s killing was captured on video which later went viral. It renewed debate over the treatment of black men by law enforcement.

“It’s a group that none of us want to be a part of,” said Johnson, of the families of gun violence, “but we have to stand together.”

An award-winning film, “Fruitvale Station,” depicting the life and death of Oscar Grant, is scheduled to be released in theaters in July.