When Marco Rubio attacked Donald Trump on the debate stage this week for using undocumented Polish workers to build Trump Tower, the developer shrugged it off.

“He brings up something from 30 years ago,” Trump shot back. “It worked out very well. Everybody was happy.”

But a look into the history of the Trump Tower, the crown jewel of the real-estate mogul’s empire, reveals the beginnings of the 68-story building were, in fact, rooted in the back-breaking labor of 150-odd Polish immigrants — most working illegally, some without full pay.

In an interview with NBC News earlier in the campaign about the Polish workers, Trump blamed the problems on a “bad contractor” and said he had been “exonerated” by the courts.

“I didn’t do anything wrong,” he said. “I wouldn’t do anything different.”

Trump has said he did not know the workers’ legal status at the time and no court has ever found that Trump Equitable, the development company, was responsible for paying them. But the tangled history of the project still could raise questions about the business practices of the man now leading the Republican pack.

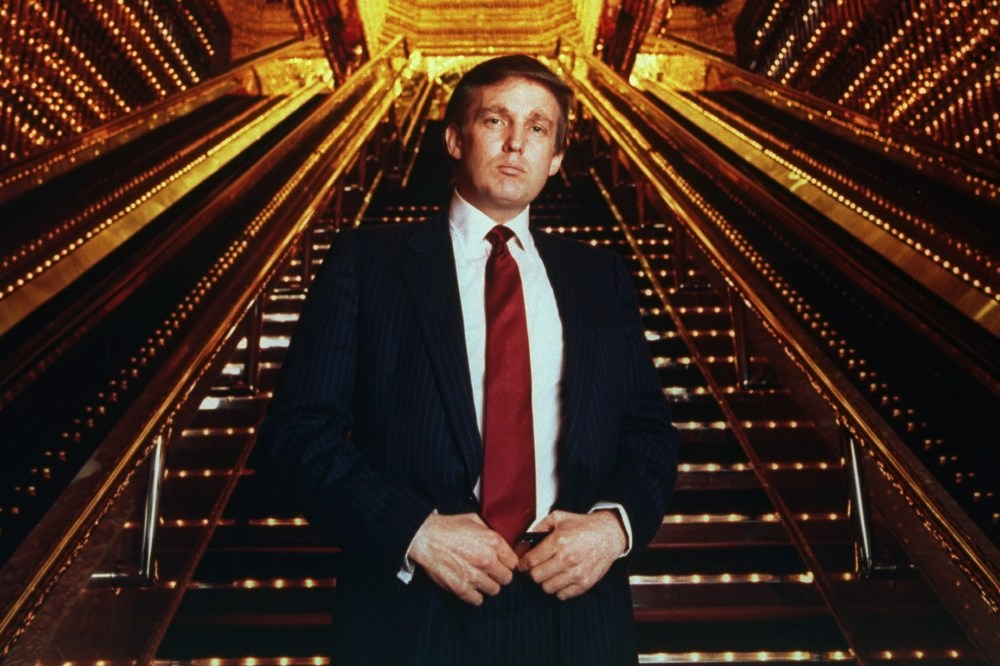

Trump launched his campaign from the marbled skyscraper that bears his name in June, pledging to build a wall along the southern border to stem illegal immigration.

Thirty-five years earlier, a group of undocumented Polish immigrants had stood on that very site, refusing to continue dangerous demolition work they had been doing around the clock for months.

RELATED: Trump at GOP debate: I’ll release tax returns when audits are done

The off-the-books workers — who testified they worked without basic safety equipment like hardhats and gloves — were supposed to earn $5 an hour. But court documents show that for weeks, they were paid nothing.

Kazimierz “Mike” Sosnowski, one of the few who had a green card, was a supervisor on the job. He told NBC News that despite 10- to 12-hour workdays, the men did not have enough money to pay rent or buy food.

“Week after week, no check,” said Sosnowski, who was a civil engineer in Poland before coming to the U.S. in 1979. He was promised $5 an hour but remembers his pockets were empty except for “a couple of dollars for coffee and a roll.”

Court records make clear the contractor who hired the men knew he was using undocumented workers without Social Security numbers.

What Trump knew — and when he knew it — is an open question.

The candidate has repeatedly denied in the past that he was aware the men were working illegally.

“Nobody has proven to me that they were illegal aliens,” he said during testimony in a 1990 trial.

But court records show that in May 1980, just five months into the demolition, Trump’s organization was well aware something was wrong.

His contractor, Kaszycki & Sons, which had never done a total demolition before, had promised to tear down the former Bonwit Teller department store for $775,000 — the lowest of 12 bids, according to the New York Times.

The House Wreckers Union found out about the job, and wanted in. They signed a collective bargaining agreement with William Kaszycki and sent some members to work at the site, for more than double the Poles’ hourly rate.

By April 1980, Kaszycki was behind schedule, over budget, and had stopped paying the Polish workers, according to testimony. They began to strike. Many took their case to John Szabo, a storefront lawyer in Queens, who later testified he repeatedly sought payment from both Kaszycki and the Trump Equitable vice president in charge of the job.

When that didn’t work, court records show, Szabo put mechanics’ liens on the property that would one day become home to some of New York’s wealthiest residents.

The case drew scrutiny from the U.S. Department of Labor, which sued Kaszycki for wage and hour violations. In 1984, a federal court hit Kaszycki with a $570,000 judgment for failing to compensate some 200 workers.

The feds did not go after Trump Equitable for payment, but in the early 1980s, a dissident member the House Wreckers Union sued Trump and Kaszycki.

The suit claimed the contractor, union shop steward and Trump vice president overseeing the job knew there were scores of undocumented Polish men working off the books — but by counting just the handful of union men at the site, they effectively bilked the pension fund out of thousands it was owed.