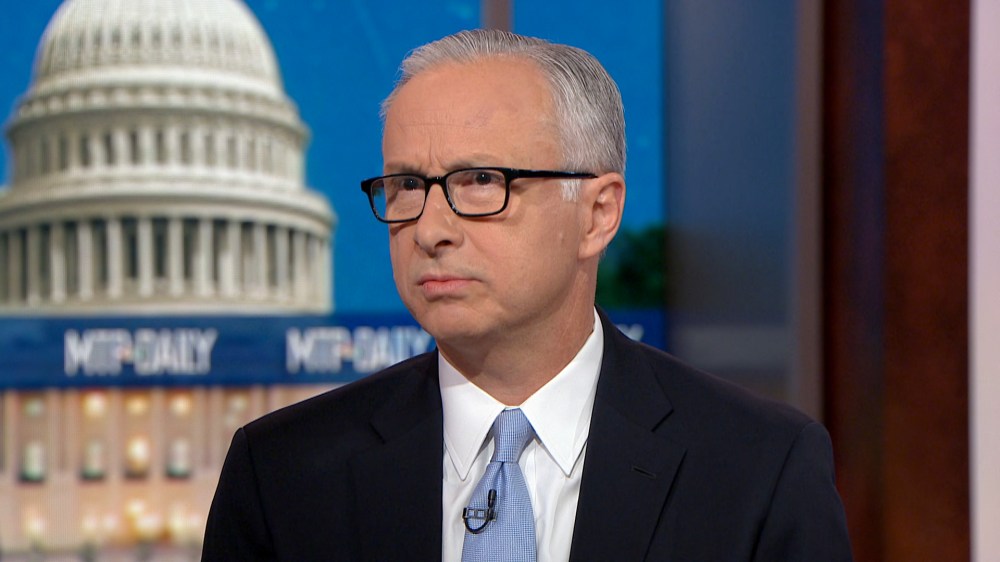

The Oath with Chuck Rosenberg

5. James Baker: Going Dark

Chuck Rosenberg: Welcome to the Oath. I’m Chuck Rosenberg. I am honored to be your host for a series of compelling conversations with fascinating people from the world of public service. All of my guests share one thing: they took an oath mandated by Congress to support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, both foreign and domestic. My guest today is Jim Baker. Jim has had a fascinating career in public service. At one point, he ran the section at the Department of Justice responsible for all FISA court litigation. You’ve heard about FISA in the news a lot lately. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. And Jim was the guy responsible for taking those warrants to federal judges for their authorization. Later in his career, Jim was the general counsel of the FBI and oversaw that FISA process from another perspective–literally across the street from the Department of Justice at the FBI. Jim is now the Director of National and Cyber Security at the R Street Institute, a nonpartisan policy research organization, where he writes and talks about these important issues. On the Oath today, Jim and I are going to discuss the encryption problem, sometimes referred to as “going dark.” Jim knows those issues as well as anybody in the country. Jim Baker, welcome to the show.

Jim Baker: Thanks Chuck, great to be here.

Rosenberg: Oh, I’m really glad that you joined us. I’ve been looking forward to this. You’ve had a remarkable career in the Department of Justice, and have held some of the most important jobs at DOJ and at the FBI, and we’ll get to that. But I want to know where it all started. Where did it all start, Jim?

Baker: My career at the Justice Department started in Detroit, Michigan, where I’m from originally. And I started with DOJ after I clerked for a U.S. district court judge…

Rosenberg: A federal judge.

Baker: A federal judge in Detroit: Bernard Friedman–is a great and wonderful person, a great mentor, helps me think about my career in the law and where I wanted to go, and so, it was through my experiences at the court that I found the Justice Department, I guess you would say

Rosenberg: Probably the most important advice I think for young lawyers–young anythings–is to find a good mentor.

Baker: Absolutely, absolutely.

Rosenberg: And he was that to you.

Baker: He was that to me, for sure.

Rosenberg: So, after your clerkship, you ended up at the Justice Department, and this thing called the Honors Program. What’s the Honors Program?

Baker: It’s one of the ways, it’s the main way that the Department of Justice will hire new attorneys out of either law school, or a clerkship. That’s pretty much the only way to get in.

Rosenberg: Yeah. And I had always thought it was a difficult program to enter, except that that’s how I got in. So obviously–

Baker: –if they had they accepted you and me, then they—then there’s something wrong with the process.

Rosenberg: At least back in the day there were no standards–they’ve tightened them up since.

Baker: It seems that way.

Rosenberg: And where did you go Jim once you joined the Justice Department?

Baker: Well my first job, actually was a bit of an anomaly. So, when I was a law clerk, my dad was sick with cancer in Detroit. And so, I wanted to stay in Detroit as long as possible and asked the Honors Program folks to allow me to start at the U.S. attorney’s office in Detroit, which was unusual. But, it was fantastic, it was a fantastic office. It was great–a great group of AUSA’s, and so I started there as a Special Assistant United States attorney for like six months, or something.

Rosenberg: So, these would’ve been the same AUSA’s that you saw as a clerk to Judge Friedman practicing in his courtroom.

Baker: Exactly, exactly.

Rosenberg: That is an unusual way to start.

Baker: It was, but it was great because I got to see and do so many things because people were eager to help me. I had known some of–some of the AUSA is when I was a law clerk and then got to know them better obviously when I was working in the office itself. But it was great. I got to do trials and pleas and sentencings and appeals and whatever anybody needed help with, I was able to pitch in and do that.

Rosenberg: And I know our listeners know this, but in case they don’t, AUSA means Assistant U.S. Attorney, somebody who is a federal prosecutor.

Baker: Exactly, a line prosecutor that goes into court

Rosenberg: And so, did you try your very first case there in Detroit?

Baker: Yeah, I did.

Rosenberg: And were you any good?

Baker: The first case I was–they allowed me to be a second chair on a trial that was run by a different AUSA, actually Jennifer Granholm, who became the governor of the state of Michigan.

Rosenberg: So, you were second chair in your first trial to future Governor Granholm?

Baker: That’s correct.

Rosenberg: What kind of case was it?

Baker: That’s a good question. I think that was a drug case and I did, you know I questioned a few witnesses, I helped with all the trial prep, questioned a few witnesses–but Jennifer was the lead and then took charge and I think she did the opening statement and the closing argument in that one. So, there was a good–it was a good first experience.

Rosenberg: Were you nervous?

Baker: Yeah, I was pretty nervous. I was more nervous, I guess when I did my first trial by myself, which was a, a trial involving a—unfortunately, a common offense: a felon in possession of a firearm. Felons are prohibited under federal law from possessing firearms after they’ve been convicted of a felony. And so, that was, that was my first case on my own and that one–yeah for sure, I was very nervous

Rosenberg: And Detroit had and has, to some extent, a significant violent crime problem.

Baker: Yes. Yeah. That’s absolute true.

Rosenberg: Was that type of work the focus of the office?

Baker: It was a substantial focus of the office at that time. Yeah absolutely. Guns and drugs was definitely a scourge of Detroit at that time and you know has remained that in various parts of the country since then. But yeah, so it was a mainstay unfortunately of the office.

Rosenberg: But you didn’t stay there that long. You came to Washington D.C. and to headquarters, Main Justice. Shortly after that. Right?

Baker: Exactly. Yeah.

Rosenberg: And what did you do when you got to Main Justice? Where’d they put you?

Baker: The first place they put me was in the so-called “Front office” of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice. My application was to the criminal division and I got in through the criminal division, and so, the first thing they did was assign me to the front office, and the person who was in charge of the front office, at that time, was one: Bob Mueller.

Rosenberg: Yeah, Mueller.

Baker: I’ve heard of that guy.

Rosenberg: I heard that name.

Baker: Yeah. So, he was the assistant attorney general for the criminal division at that point time. And I was assigned to work with his office, and then assigned to a particular deputy assistant attorney general, who worked in the chain of command for, for Bob, a person named Mark Richard who again, was a fabulous mentor, coach person

Rosenberg: When I think back on my time at the Department of Justice, what I really think about, are the people, and in particular, any number of people who were patient with me and kind to me and who helped me find my footing.

Baker: Absolutely. I mean this is something I tried to say to law students and younger attorneys now, that really anybody from any walk of life–that the people you work with is critically important. People are often attracted to the title or the job description something like that. But it’s really the people that are the most important thing

Rosenberg: Right, and the titles in the end don’t matter it’s the people along the way.

Baker: Exactly.

Rosenberg: I know you did some time–this makes you sound like an inmate. I know you spent some time in the fraud section of the criminal division at the Department of Justice. But I wanted to fast forward a little bit because you went to this place within DOJ called the Office of Intelligence Policy and Review.

Baker: So, it was a component of the Department of Justice, which meant it was a separate organizational unit within DOJ.

Rosenberg: What were they responsible for?

Baker: They were responsible for advising the attorney general, other DOJ leaders, and the intelligence community, on a variety of legal and policy issues related to the Conduct of Intelligence.

Rosenberg: The Conduct of Intelligence–so what is the Conduct of Intelligence? And by the way, why is the Department of Justice conducting intelligence?

Baker: Well, for several reasons. One, is that under the, then existing, and now still existing, but amended main executive order that President Reagan actually issued, called Executive Order: Twelve Triple 3, 1 2 3 3 3. That’s the main executive order that governs the functions of the intelligence community, and that gives the attorney general certain oversight authorities with respect to intelligence activities in the United States.

Rosenberg: So, the reason the Justice Department is conducting intelligence is because President Reagan directed them to.

Baker: That’s basically right. And then, in addition, certain statutes give a role to the Department of Justice. In particular the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA.

Rosenberg: And we’ve heard a lot about FISA. But I think it would be really important to explain what it is and what it permits, and how the Department of Justice conducts itself in front of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. So, what is FISA?

Baker: FISA is a statute that regulates certain intelligence collection activities by elements of the U.S. government.

Rosenberg: And so the collection is pursuant to statute and pursuant to court authorization.

Baker: Most of it. The FISA is a–it’s a limited statute it covers a lot, but it’s still limited. So, it mainly covers electronic surveillance, physical search, and certain other activities: collection activities inside the United States. It has relevance overseas and we can get into the details of that as well. But, especially when it was first created, Congress made the decision: we’re only going to regulate the activities of the intelligence community mainly as they pertain to the United States. We’re not going to try to regulate all the activities overseas.

Rosenberg: And so, what is this place you work, OIPR, have to do with FISA? What’s their role in the conduct of intelligence and adhering to the FISA law?

Baker: When I started out there, there was–the head of the office was called the Counsel for Intelligence Policy.

Rosenberg: Which you later became.

Baker: I later became. There were two deputies–one for intelligence operations, and one for intelligence policy and they had folks that worked for them. Even so it was a very small office. I was hired into the operations side, which dealt with all the FISA applications and other activities involving oversight of the FBI’S intelligence investigations. So, that’s mainly what we did

Rosenberg: And what year did you start there, Jim?

Baker: I started in 1996.

Rosenberg: And so, when you describe it as a relatively small office, it’s worth pointing out that this was prior to the attacks of 9/11

Baker: Correct

Rosenberg: Things changed dramatically.

Baker: Absolutely. So, we had about I think, when I started, there were six other attorneys, I think it was, who were working on FISA applications as we did all of them. And at that time, there were somewhere around 800-900 a year I think.

Rosenberg: Total FISA–

Baker: –total FISA applications.

Rosenberg: And when we talk about a FISA application, that’s an application that goes to a federal judge, and then she reviews it, and if it’s appropriate, signs it–authorizes the collection.

Baker: Right. The FISA statute created the FISA court, or the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, sometimes referred to as the FISC: F-I-S-C. And so, it’s one of those judges that we go to–those are regular district court judges from around the country selected by the chief justice to sit on the FISA court for seven year terms, and they hear those cases in addition to doing their regular work back in their home districts.

Rosenberg: So, your unit was just six lawyers.

Baker: I think it was seven including me. Yeah, something like that. The East Africa Embassy bombings in 1998 really started a huge transformation for us.

Rosenberg: Those were the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

Baker: Correct. So that started a big change. And then, in addition, a very significant event for us was the so-called Millennium Crisis, which was the crisis right before January 1st, 2000 when there was a real threat from Al-Qaeda to attack locations inside the United States. So, we worked intensively on that, and that was highly transformative for a lot of reasons as well.

Rosenberg: Did the number of lawyers increase?

Baker: it increased over time, slowly. So that’s why the Millennium Crisis was a huge drain on our resources as well as on the resources of a number of other agencies. It was also government at its best. All of the inter-agency: FBI, the rest the intelligence community, DOJ, we are all just working seamlessly to make sure that nothing was dropped. And so, that was great but it was a transformative experience and really showed what some of the resource gaps were, I think, and so we started to increase our resources even before 9/11.

Rosenberg: And by 9/11, are you still a line attorney in OIPR or do you have another responsibility?

Baker: Yeah. By 9/11 I was the head of the office. So, I had moved from a line attorney up to a deputy for operations and then became the head of the office.

Rosenberg: What was the change in the work of your office after 9/11?

Baker: So, there was a substantial change–this is a phrase that General Hayden uses from time to time: the variety velocity and volume of the work. Obviously, it focused substantially on counterterrorism. And in particular, one thing that we did was expand the use of so-called emergency authorizations under FISA. There’s–there had been since the beginning a provision under FISA, where the attorney general could orally authorize a surveillance or a search.

Rosenberg: On an emergency

Baker: On an emergency basis, if you met certain requirements of the statute. And that was used, but seldom used before 9/11, and then after 9/11, we had to use it a lot.

Rosenberg: Why did you have to use it a lot after 9/11?

Baker: Because of the urgency of the, of the subjects of investigation that the FBI had, and the urgency of the need to find out what was going on, especially to learn whether there was another plot. I mean, I think people don’t focus on that much right now but there was a substantial concern that Al-Qaida was planning something else after 9/11 and we wanted to get the bottom–get to the bottom of that and prevent anything from happening. Technology started to change too. And with the increased use of the Internet and so that changed the level of technical complexity of the surveillances that the FBI wanted to do.

Rosenberg: Jim, I don’t want to talk about particular cases, and I know you can’t, and won’t talk about particular cases, but in general I think there’s a lot of misperception about FISA applications and FISA warrants and how the work is done at the Department of Justice and at the FBI to bring a FISA warrant to court. What’s the process like?

Baker: So, let me focus on the time that I was at OIPR back in those days. It was an extremely rigorous process that got more intense over time.

Rosenberg: By more intense, do you mean more rigorous?

Baker: More rigorous, in terms of making sure that the applications were accurate and that there were procedures for ensuring, to the best of the government’s ability, that they were accurate.

Rosenberg: So, take me through a hypothetical application. Where does it start, and where does it end, and what happens to it in-between?

Baker: Let me back up from that. One thing to remember about FISA, I think is sometimes confusing for folks, is a FISA surveillance is an investigative tool. It’s not an investigation unto itself. And so, it is something that the FBI or NSA would assess was needed as part of the intelligence collection, intelligence investigations that they were conducting. So, with respect to the FBI, the FBI would be conducting an intelligence investigation. So, when I say that, I mean either a counterterrorism investigation, or a counterintelligence investigation, they’re chasing a spy or a terrorist. They thought that would be helpful to conduct electronic surveillance or search.

Rosenberg: You know, I think that’s a really important way to think about it. Just bringing to the criminal context where I spent most of my time in the Department of Justice. A search warrant on a bank robbers home is not an investigation in and of itself. The investigation is of the bank robbery and the search warrant is a tool to obtain evidence lawfully pursuant to court order in that bank robbery investigation. Is that a fair analogy?

Baker: That’s a fair analogy. Exactly. You have a legal basis under applicable procedures, which are attorney general guidelines, basically, telling the FBI when you can do investigations that include a FISA. And so, once you’ve met that threshold and the FBI decides that it wants to use a FISA, then you go to the FISA court and establish probable cause to believe that the target of the surveillance or search is a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power. But, it’s probable cause, it’s not proof beyond a reasonable doubt. And so, you–and you do that in the middle of an investigation when you’re still trying to figure out what’s going on

Rosenberg: And the probable cause standard, for our listeners, Jim comes from where?

Baker: Comes from the Constitution.

Rosenberg: The Fourth Amendment.

Baker: Exactly. And so, courts have defined it in a variety of different ways but, a shorthand way, there’s many shorthand ways, but a shorthand way–it’s a fair probability based on the totality of the circumstances that a particular fact or circumstance exist.

Rosenberg: Right. And by design, then because it’s an investigative step, and not the investigation in and of itself, it’s a relatively low standard.

Baker: It’s low. There’s no–and people have argued about this a lot–there’s no mathematical number that you can assign to, to probable cause. It’s not 49% percent or 51, or anything like that if you are thinking about it in numerical terms, you’re gonna make a mistake.

Rosenberg: But you can put it on a spectrum and talk about it. For instance, the highest standard of proof that I know of in the law is proof beyond a reasonable doubt, which is what is required to convict someone a trial, and probable cause is manifestly lower than proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

Baker: That’s right.

Rosenberg: But explain to me how that application actually moves through the FBI and then comes to your office at the Department of Justice for your review and then what happens to it.

Baker: So, there were requests and then there are applications. The FBI would make a request for a FISA surveillance in connection—you know, the FBI field office in, I don’t know, Detroit, wherever, would be working on a case. And at the level of the squad working on the case, they would decide: yes, let’s do a FISA. We have the probable cause we think, were justified under the attorney general guidelines, and internal FBI procedures…

Rosenberg: Meaning, we need it

Baker: We need it. We think we need to conduct this search, or we need to do the surveillance because that’ll help us figure out exactly what’s going on here. And so, they will put together a request at the squad level, and then that works its way through the FBI hierarchy, at the field office and at headquarters, before it came over, to our office at OIPR. So, there are a lot of internal reviews by the FBI by agents by supervisors by lawyers before it got to us and then, we would take the request and turn it into an application. And then that also would have a review process by going back and forth between the FBI and DOJ to make sure that it was correct, make sure we had the facts right, make sure that we, at DOJ, interpreted what the FBI was saying correctly, and then they would go through a process of reviewing the underlying documents to make sure that they supported all the allegations in the application.

Rosenberg: So, you mentioned earlier that there were emergency authorizations and those obviously moved quickly, but in a more routine case, this process of back and forth: requests and applications, review in several different buildings by many different people, could take weeks.

Baker: It could take–it could take weeks. Yes, it could take weeks–it could take months, or could take a day. I mean it depending on what level of emergency or urgency it was–

Rosenberg: And how you prioritize.

Baker: And how you prioritize those. So, it was a constant struggle to prioritize it. OIPR, at various times, was accused of being a roadblock, an impediment, slowing the process down, and so on and so there was this constant struggle, this constant stress, this constant debate between the Department of Justice, OIPR, and the Bureau and other folks including you know, hearing about it from members of Congress, about whether OIPR was a rusty gate– we were a gatekeeper, but we are a rusty gate and so on. And this assessment of whether or OIPR’s review was too rigorous, or not rigorous enough, changed over time depending upon who was looking at it. But, the, the rigour of the review, it was consistent even though it improved over time I guess I would say.

Rosenberg: So, was it a fair criticism?

Baker: I didn’t think it was a fair criticism because I thought that we were trying to work on the priorities of the U.S. intelligence community. And if they prioritized work, it was dealt with accordingly. So especially after 9/11, we were in constant communication with the FBI and other elements of the intelligence community about what the most important cases were. And also with the attorney general, I mean we were getting direction from the attorney general about what the most important cases were. I’m sure if you talked to folks from the FBI back in those days, they wouldn’t say “Oh my God OIPR you take forever on these various things,” because you know legitimately to every agent to every field office their request is the most important. But we were running a national program and, and we had to balance our workload based upon the national priorities of the of the federal government, of the intelligence community.

Rosenberg: One of the interesting things about being a lawyer in OIPR, is that when you appear before the federal judge in order to get her to authorize the FISA warrant, you’re appearing alone, meaning the other side is not represented. We call it ex parte.

Baker: Correct.

Rosenberg: In my view, that imposes a special burden on the Department of Justice. And I was wondering if you would talk about that.

Baker: Your view and the view of the ethical roles that we’re all subject to. Right. Because when you’re appearing ex parte, you have the highest duty of candor to the tribunal that exists under, under the ethical rules. So, you have to inform the court about all of the material facts relevant to the application, whether you know–the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Rosenberg: And there seems to be this sense out there that if the other side’s not there then justice can’t be done. That wasn’t my experience because when I brought criminal search warrants to a federal judge, and they were reviewed, I always wanted to ensure that the product I was putting in front of them was thorough and accurate in every respect. In other words, I felt more of a burden because there was no one there to challenge it.

Baker: I felt that burden tremendously.

Rosenberg: Was that the ethos of the office?

Baker: That was definitely the ethos of the office the whole time that I was there. That’s not to say we didn’t make mistakes, of course. But, our objective was to do everything possible to avoid those.

Rosenberg: But what happened when you did make a mistake?

Baker: We did everything we could to figure out whether a mistake had been made and then we corrected it. We told the court. We told the court, we told the attorney general, we told Congress.

Rosenberg: Another important point. You have an obligation to the court when you discover a mistake.

Baker: Absolutely.

Rosenberg: So, your work at OIPR is not just overseen by federal judges it’s overseen in other ways.

Baker: Yes, especially by the attorney general. Yeah because we had to take applications to get signed, either by the attorney general the deputy, in most cases, and you know, this the same thing. I don’t want to be bringing cases to the attorney general that are messed up or screwed up in some fashion.

Rosenberg: Who else oversees the work of all OIPR.

Baker: A couple other bodies. Internally within DOJ, is the inspector general so we had many times when the inspector general would review our work in a variety of different contexts. So, that was, that was definitely the case. And then in addition, Congress, especially the intelligence committees of both houses of Congress. So, we had to submit on behalf of the attorney, general reports twice a year to the intel committees that were classified at a high level explaining the work that we had done explaining when we had uncovered problems and things of that nature. And then we would frequently go up and do briefings, there’d be hearings, I appeared before Congress many times in various hearings with members and so on, usually behind closed doors.

Rosenberg: Because of the classified nature of the work.

Baker: Exactly.

Rosenberg: And in your experience, was the oversight by Congress real or illusory?

Baker: No, it was real. I mean especially the staff members of those committees back in those days for sure, they went over those reports with a fine tooth comb, asked us lots of questions, we go up there for a long time. I experienced it as real oversight.

Rosenberg: You know, Jim going back to my experience as a federal criminal prosecutor, I know that search warrants are almost never denied by federal judges. And I always thought there were two reasons for that. One, is that it just requires probable cause, a relatively low standard. But the other is that we’re really careful when functioning in this ex parte environment, to make sure that the product we’re putting in front of them is sound and accurate and compelling. One of the criticisms of the FISA process and the FISA court by extension, is that it denies very few applications. Is that true.

Baker: That’s true.

Rosenberg: Why?

Baker: The FISA statute requires that there be a number of signatures on applications before they can go to the court. So, the agent, lawyers at DOJ, a high ranking national security official, like the director the FBI, and the attorney general. So that is a process that takes some amount of time while that’s going on. We figured out that well, why don’t we give the court a copy of the application as it’s moving through the system. And that way, if they have questions, they can ask them. We can answer them. We can try to get additional information. Or, if they spot something that’s screwed up, we’ll fix it. In addition, if they tell us: well we don’t think this application meets the requirements of the statute, we could have a dialogue with the court, and change it. So, there was a robust back and forth between the Department Justice and the court before the thing even showed up in court.

Rosenberg: Now, that’s a bit different than my experience because the only time we would see the judge is when we were presenting to her the application for the search warrant. We didn’t have a back and forth in criminal cases. Was that unusual and proper appropriate. How did that strike you?

Baker: I thought it was totally appropriate. And yeah, it’s unusual for sure. I mean there’s much about the FISA court that is unusual in federal law. There’s no doubt about that. But it was–it was–given the urgency of everything that we were trying to do, the importance of it, the need to get it right the first time, it was–it is what worked, at least, in terms of getting the matters in front of the judge and the legal advisers because they had permanent legal staff, to allow them the time to focus and assess these cases reasonably.

Rosenberg: And I’m sure your, your experience is similar to mine in this respect, if a federal judge thought you didn’t have it, they wouldn’t be hesitant or shy to say that.

Baker: Not at all.

Rosenberg: How long did you spend at OIPR, Jim, after 9/11?

Baker: I stayed there until 2007.

Rosenberg: And how big had the staff grown by then?

Baker: We grew from this small office of around 20 people when I first started there, to an office of about 125 when I left, and we went from about a 1 million-dollar budget up to about 30 million, so it was a huge change over time.

Rosenberg: And you mentioned in the mid and late 1990s you were processing 800 to 900 applications a year. I assume that number changed dramatically too.

Baker: Yeah, that went up to somewhere around 2000 or something like that. There was quite a bit. And on top of that, we built–and we built a secure classified I.T. system and ran that. We built a new way to write the FISA applications that was highly automated that made things a lot faster and more accurate. And so, we had contractors come in to do that. We were we were innovating constantly in order to make sure that the system was as efficient as possible and as accurate as possible.

Rosenberg: An interesting side note. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, the federal judges used to physically sit in the Department of Justice building. And that changed.

Baker: That changed, yeah.

Rosenberg: When, and why?

Baker: It was not that long ago, I don’t remember the exact year. Look, the fact that the court was in the Department of Justice was mainly an issue of convenience and security. And again, back to your earlier point, these are independent, federal judges who spoke their mind, and who, on any number of occasions, told me very clearly what it was that they thought, especially when they were not happy with something.

So, the idea that somehow, they gave up their independence when they walked in the door of the Justice Department was bogus.

Rosenberg: Yeah, I had always thought that was a laughable claim–the notion that an Article 3 federal judge was captured by the Department of Justice simply because they sat in the same building–just didn’t make sense to me. But nevertheless, they got their own place.

Baker: They got their own pace, they’ve got their own place. And they wanted, you know, I mean they wanted to make sure that both in fact and appearance the court was independent and this was a thing that people brought up constantly. And so, in addition look it gave them more independence administratively to run the court, to have their own physical space, and to be in charge of things, as opposed to having to deal with the DOJ bureaucracy

Rosenberg: Appearance matters too. We have to be fair, and we also have to appear to be fair and I think both of those things are important.

Baker: I agree completely.

Rosenberg: So, you left the department for a time, to go into private sector work.

Baker: Yes, I did some teaching, did a fellowship, and then went to the private sector.

Rosenberg: But, you came back.

Baker: I came back.

Rosenberg: You’re like me, you can’t stay away. When did you come back and why?

Baker: I came back in 2009 to work for David Ogden, who was the Deputy Attorney General at the time, to help him with his national security and cybersecurity portfolio and to help the other team members including Lisa Monaco, who was there at the time, and who had quite a full plate dealing with the various issues that she was dealing with.

Rosenberg: Lisa is also one of the guests on the Oath.

Baker: Very good.

Rosenberg: So, how long did you stay in the deputy attorney general’s office?

Baker: I was there for about two years, I think it was.

Rosenberg: Did you like that work?

Baker: I like that work. That work was interesting and challenging. My favorite part of the work, which I didn’t expect, I was put in charge of the Rule of Law program.

Rosenberg: What does that mean?

Baker: So that means that at that time, the Department of Justice had teams of attorneys, mostly assistant U.S. attorneys, assigned to Iraq and Afghanistan to help them with their rule of law development programs. And I ended up being assigned that responsibility, to be in charge of that program, working with a great team, a guy named Brian Tomney, in particular, in the office who just worked incredibly hard on these programs. They were very challenging, obviously risky environments for our folks to be in. It was a fantastic and very, very rewarding experience.

Rosenberg: But you left the department again.

Baker: Left the department again.

Rosenberg: To go to the private sector again.

Baker: I went back to the private sector. Yep.

Rosenberg: OK. But you couldn’t stay away

Baker: I couldn’t stay away, even that time, yeah.

Rosenberg: When did you come back, and why?

Baker: I came back to–well to the Department of Justice, this time to the FBI.

Rosenberg: Which is part of the department.

Baker: Is part of the–just the part of the Department of Justice–another component, just like OIPR was a component. And so, I used to laugh about the fact when I was the head of OIPR, I was I was technically on the org chart the same rank as Bob Mueller…

Rosenberg: But we know in real life–

Baker: in real life, right.

Rosenberg: That’s just not true.

Baker: And so, yeah, I came back and went to work for the FBI as a general counsel.

Rosenberg: So, Jim Comey was the FBI director at the time.

Baker: Exactly.

Rosenberg: And so now you’re on the other side of the street ,both literally and figuratively from the place you used to work, but you’re still involved in the national security work of the FBI.