In 2006, I was very fortunate to win an eight-year legal battle to recover five Gustav Klimt paintings taken by the Nazis, which is the basis for the film “Woman in Gold,” opening today. (Ryan Reynolds plays me in the film, and Helen Mirren plays my client, Maria Altmann.)

At the screenings I have attended, I have been repeatedly asked whether there are still other paintings yet to be returned to their rightful owners. The answer is, unfortunately, yes. Below are just three of the cases I have worked on.

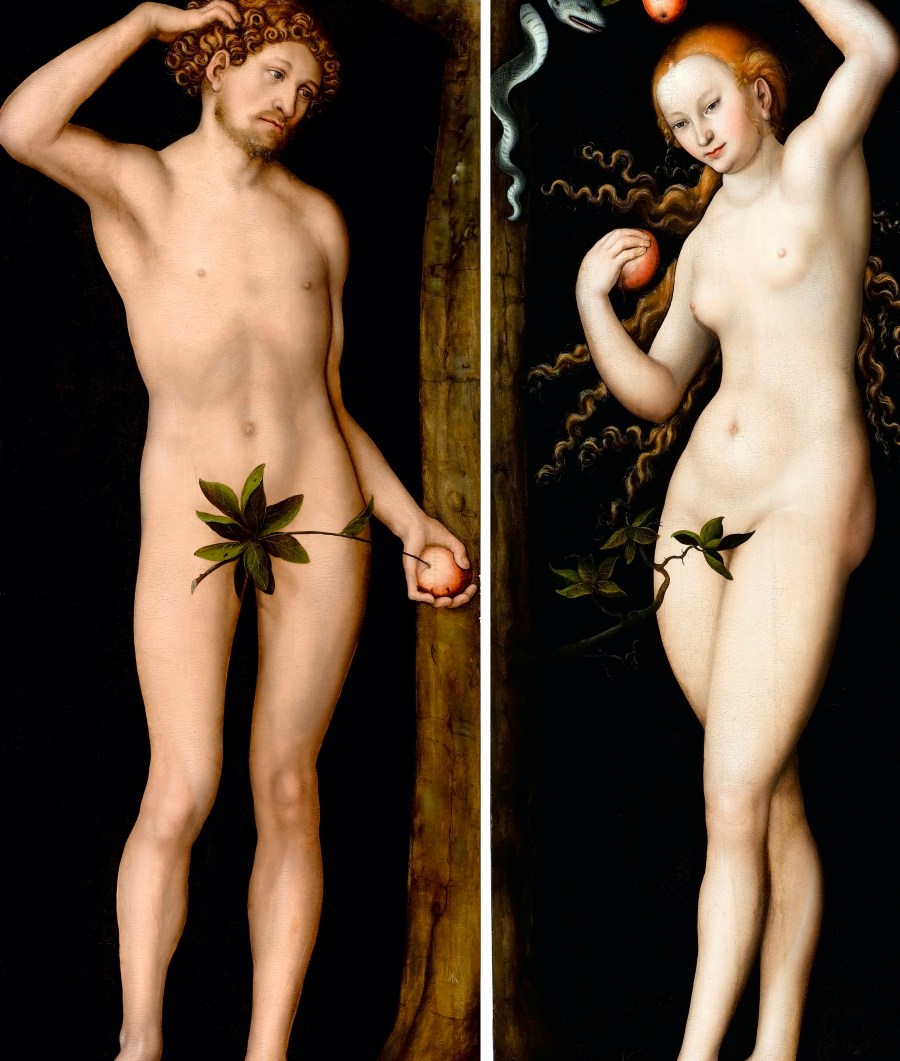

Adam and Eve, Lucas Cranach the Elder (1528)

If you ever watched the opening sequence for “Desperate Housewives,” then you’ve seen the diptych “Adam” and “Eve,” by the famed German artist Lucas Cranach the Elder, which presently hang in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California. These two paintings were owned by a Dutch Jewish art dealer named Jacques Goudstikker, who fled with his wife and young son as the Nazis invaded the Netherlands in 1940.

Sadly, Jacques died in a shipboard accident while the family was crossing the Atlantic. His entire art collection was seized by the Nazis, and “Adam” and “Eve” were ultimately taken by Hermann Göring, the number two Nazi after Adolf Hitler.

Some of Jacques’ paintings were recovered by the Allies at war’s end by the so-called Monuments Men (portrayed in George Clooney’s film) and dutifully returned to the Netherlands. But the Netherlands failed to return them to Jacques’ surviving family.

In, 2006, the Dutch Government finally returned the works to Jacques’ sole surviving heir, after determining that the family had been treated unfairly after the war. Unfortunately, “Adam” and “Eve” were not returned, because the Dutch Government in 1966 improperly sold them to George Stroganoff-Scherbatoff. Stroganoff later sold the paintings to foundations associated with the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena.

Rather than return these paintings, which the Norton Simon Museum does not dispute were looted by the Nazis, the museum has spent years in litigation posing procedural objections instead of doing the right thing and returning the paintings to their rightful owners. Last year, one of Norton Simon’s grandsons also called for a “just and fair solution” to the case.

Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl, Gustav Klimt (unfinished, 1918)

In the film “Woman in Gold,” Helen Mirren (playing Maria Altmann) stops to marvel at this painting hanging in the Belvedere Gallery in Vienna, noting sternly that Amalie was murdered by the Nazis. What the film doesn’t mention is that this painting hung until 1938 in the bedroom of Maria’s uncle, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer. Ferdinand fled when the Nazis invaded Austria in the infamous Anschluss of March 1938, and died in exile in Switzerland in 1945, shortly after the war ended. By that time the painting had made its way into the hands of an Austrian art dealer, who ultimately donated it to the Belvedere when she died in 2001.

Rather than return this obviously looted painting, an Austrian arbitration panel concluded that it should stay in the Belvedere. The arbitrators said they were not certain exactly how the painting left Ferdinand’s home, and believed (despite a mountain of evidence concerning the Nazi liquidation of Ferdinand’s entire estate) that Ferdinand might have decided to give the painting to Amalie’s family. How this could have been accomplished while Ferdinand was in exile, the arbitrators did not explain.

The panel refused to apply long-standing Austrian restitution laws, finding that a newer art restitution law enacted in 1998 did not incorporate them. The Austrian Supreme Court upheld the decision, finding that the arbitrators’ construction of the law was “plausible.” However, Austria’s art restitution advisory board has since clarified that the old restitution laws should continue to be applied. And yet, so far the Austrians have refused to reconsider the case. The looted “Portrait of Amalie Zuckerkandl” continues to hang in the Belvedere to this day.