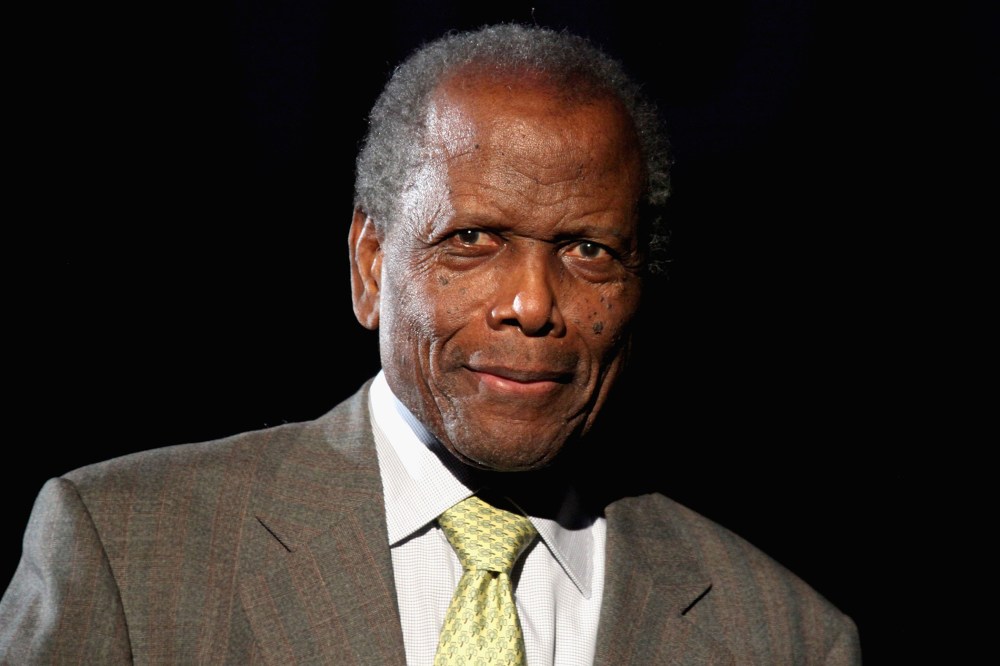

Depending on the generation of the person you ask, the name Sidney Poitier can either evoke a kind of peerless reverence or apathetic indifference. The iconic actor, who turned 89 in February, hasn’t appeared in a major motion picture in nearly 20 years, and yet his screen persona — described by African-American Film Critics Association president Gil Robertson to MSNBC as combination of “integrity, class and sophistication” — has reverberated in Hollywood in ways both big and small since his first big screen appearance in 1950.

This week, New York City’s Museum of the Moving Image is holding a retrospective on his illustrious career, curated by the co-editor of “Poitier Revisited: Reconsidering a Black Icon in the Obama Age,” Vassar College film professor Mia Mask. According to Mask, the program was initiated in part because of the current, racially polarizing political climate and national conversation on diversity in film and television inspired by the #OscarsSoWhite controversy. This is the “perfect time” to revisit the actor’s often overlooked filmography, he said.

“Poitier was at the forefront of trying to change the image of black men and black people,” Mask told MSNBC on Wednesday. And while she believes he has had a radical impact on how white audiences, and by extension, white people perceived African-Americans, the issues that some of his films confronted — from racial profiling to police brutality, as well as unflattering, stereotypical portrayals of black masculinity in the media — still persist to this day.

RELATED: ‘Selma’ star: Hollywood is afraid of white guilt

In the late ’50s and 1960s, Poitier was for many white people a window into the black experience. He was what the New York Times once described as a “an ambassador to white America and a benign emblem of black power.” His virtually flawless and accommodating protagonists helped usher in more humane portrayals of African-American life, while helping the country prepare for the arrival of a real-life black leader like President Barack Obama.

For black audiences, though, his films connoted quality and they also presented an image of themselves they were craving to see on screen. “Sidney Poitier [films] were like buying a Nancy Wilson album or a Prince album, you knew what you were getting. If he’s [in a movie] I know it meets a standard of excellence I know I’m going to appreciate,” said Robertson. “He is never going to do ‘Booty Call,’ he’s never going to do something that makes me sorry that I spent the money.”

“Sex and the City” star Blair Underwood is one of the actors who bore the fruits of Poitier’s labor. “Sidney Poitier is very much the Jackie Robinson of Hollywood,” he told MSNBC on Wednesday. “He gave you something to aspire to. He is the man who inspired me to go and become an actor.” For Underwood, Poitier’s strength and humanity had an appeal that stretched beyond race, and his films usually had a message that was timely and true.

According to Underwood, who recently dined with the iconic actor and considers him a mentor, back in 1994 when Underwood was grappling with whether to

take on a role as a serial killer in the thriller “Just Cause,” Poitier told him, “I came along at a time where I didn’t have a choice [in roles]. I didn’t have the luxury when I was coming a long. I did that so you didn’t have to. So you play that role and you play it well.”

That conversation left an indelible impression on Underwood, who has seen a dramatic shift in the diversity and the variety of representation of people of color in film and television over his own award-winning career. Poitier disciples see a direct line from the actor’s contributions to cinema to the work of Denzel Washington, Will Smith and even television producer Shonda Rhimes, figures who Mask says “combine elements of the Poitier persona into a repertoire.”

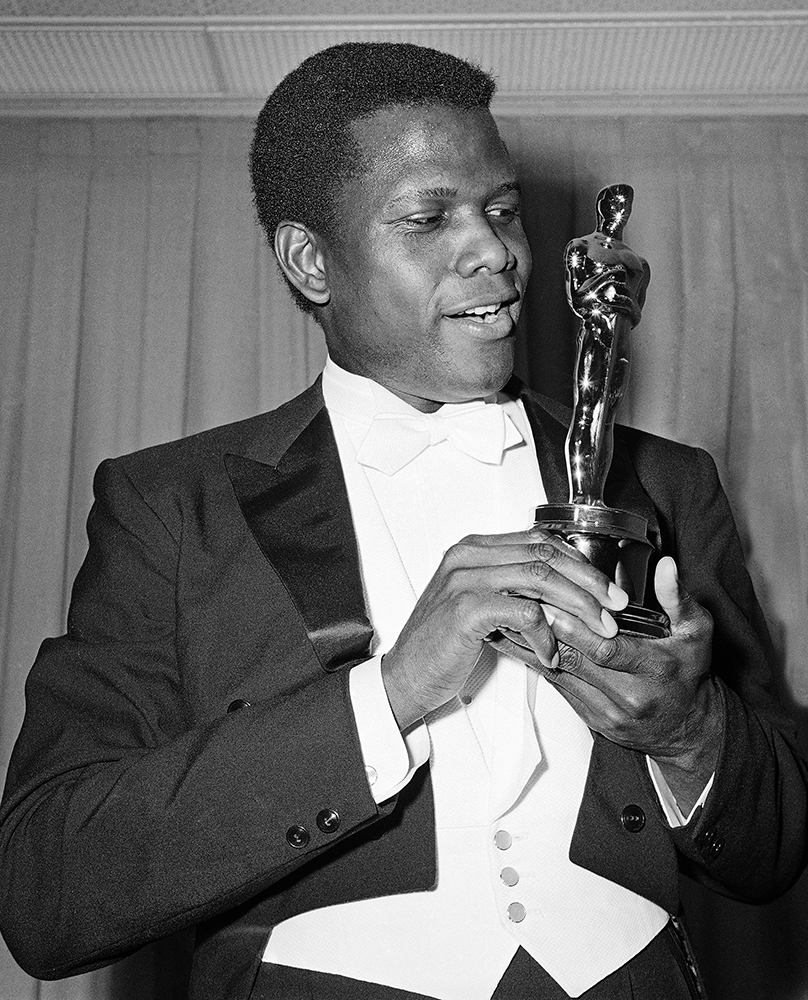

Still, the fact that Poitier’s films and the man himself were often both radical is often lost on younger film buffs. Take for instance his role in the 1967 best picture Oscar winner “In the Heat of the Night.” Poitier played Virgil Tibbs, a black police officer from the Northeast who is drawn into a murder investigation in the deep South while he is passing through. His character must confront prejudices from not just suspects, but local law enforcement as well. In a pivotal scene, Poitier confronts one of the wealthy elites of the community who takes issue with his high status as a black man.

The elderly white man slaps Poitier, who quickly returns a blow. It was a quiet but profound moment in cinema history, particularly for African-Americans.

“I think I watched that scene 50 times,” said Robertson. “It should be required viewing for every African-American, particularly our young men.” To him, the scene said “You’ll respect me or these are the consequences. I’m standing my ground.”

“The slap [by Poitier] was not in the initial script,” added Mask. “Poitier told producers either you change the script of I don’t make the film. This was a radical thing for a black actor to be able to do. To say, ‘If you want the Poitier brand in this film you’re going to have to comply.”

Of course, establishing a brand as a black actor in Hollywood at that time was an arduous process, which occasionally meant taking roles Poitier considered beneath him (“Porgy & Bess”) or those that were incredibly compromised by the social morays of the time. “Poitier was made to over-compensate for his blackness, for his black identity,” said Mask. “This was one of the things that was problematic for black audiences in the ’60s.”