RAPID CITY, S.D. — “It was supposed to be a month,” Jeavene Running Shield says. But it’s now been three years since the six of them moved into this cramped motel room: Jeavene, her husband, the three grandchildren, and their daughter Betsy, who’s sleeping on the blankets spread over the floor after her 13-hour shift at Taco John’s.

Cereal boxes, trail mix and salad dressing crowd the single table where they prepare their meals, since there’s no kitchen in their makeshift home.

If Betsy got a raise, “we’d be able to get a place,” says Running Shield, 53, who was recently laid off from her housekeeping job at a local hotel. That’s one reason why she’s planning to vote for the minimum wage increase that’s on the ballot this year in South Dakota. A minimum wage hike could boost her future income, too: While her most recent job paid $9.46 an hour, her previous housekeeping job paid just $8.00 an hour — $0.50 below the newly proposed minimum in South Dakota.

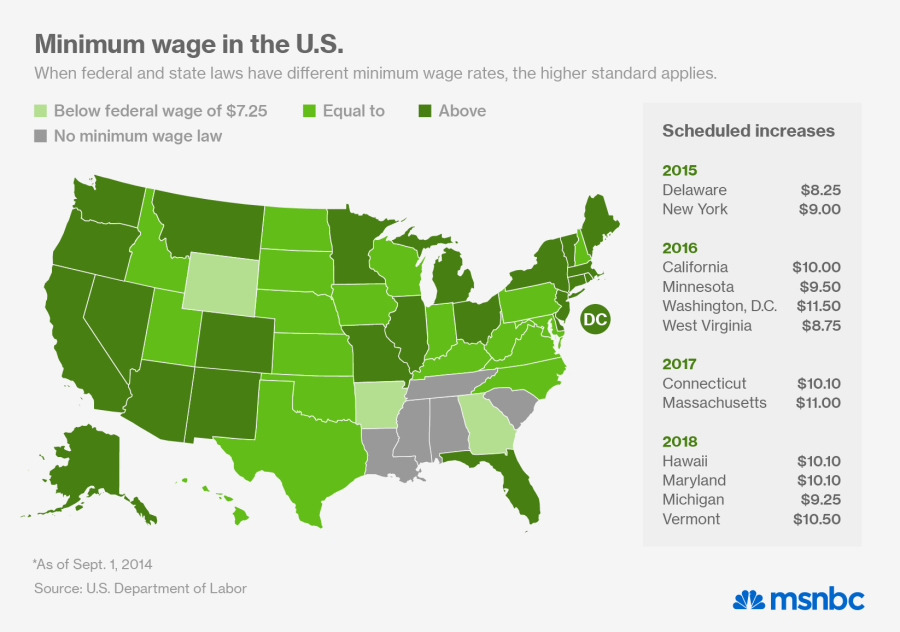

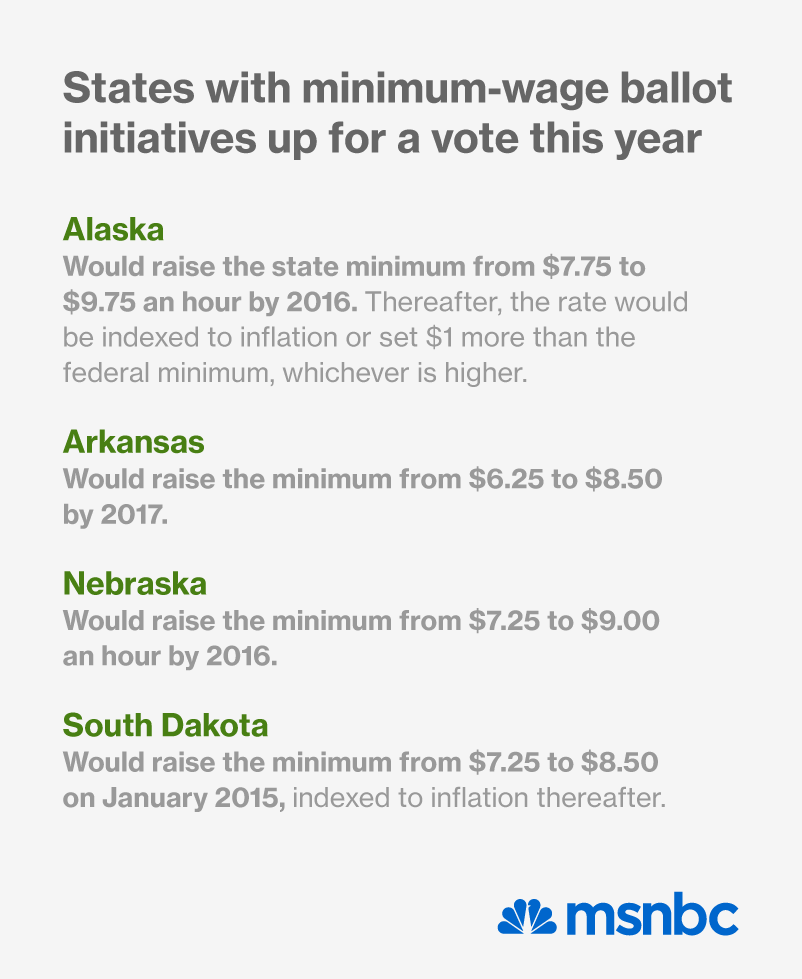

Despite President Obama’s record-low approval ratings, a minimum wage hike — one of his party’s biggest priorities — could move forward in a handful of red states across the country. Besides South Dakota, Nebraska, Arkansas and Alaska have ballot initiatives that will allow voters to decide in November whether to increase the statewide minimum wage. A blue state, Illinois, has a non-binding vote as well.

All the proposed increases would be more modest than the $10.10 federal minimum that Obama and national Democrats have proposed. But unlike the federal wage hike, which Republicans have steadfastly blocked in Congress, the state-level hikes actually have a chance of passing this year.

“Minimum wage increases have been popular with voters across the country — every state-level measure in the 21st century has passed — and opinion polls suggest that this year’s measures are headed to passage as well,” says John Matsusaka, executive director of the Initiative and Referendum Institute at the University of Southern California.

Even in a state like South Dakota — which hasn’t supported a Democrat for president since 1964 — the proposed wage increase from $7.25 to $8.50 an hour has consistently polled better than any major statewide candidate, Republican or Democrat. Under the initiative, tipped workers like waitresses would also see their hourly minimum rise from $2.13 to $4.25, and all the new wages would also be indexed to inflation going forward.

Two consecutive polls from SurveyUSA have shown the ballot initiative with 61% support in South Dakota. As elsewhere, opponents of the measure say that it would kill low-wage jobs. But with an unemployment rate at 3.4%, compared to 5.9% nationally, the pressure for more jobs isn’t nearly as urgent; South Dakota is working harder to fill empty slots than to create new ones.

Running Shield’s 28-year-old son Antonio is skeptical, though, that a $1.25 hourly raise would ultimately mean much for the state’s workers.

“Another few more dollars a week, that’s nothing — it’s just more for them to take,” he says, describing how taxes eat up his own paycheck.

But that doesn’t mean he’s happy with the way things are. “Something needs to happen,” says Antonio, whose pants are still dusty from his landscaping job. “10, 11 dollars, is — what do you call it? — a living wage.” Even at his salary, at $12 an hour, he still relies on food stamps to feed himself, his wife, and his young son, as he rarely can get 40 hours a week.

And when the food stamps run out, “we go to the food bank — or come here,” he says, sitting in his parents’ motel room.

* * *

With exactly one week until the November 4 midterm election, the opposition to Initiated Measure 18 has gotten more organized.

Low-wage workers like waitresses make more than people think, says Jim Ashmore, who runs a land-titling business in the small town of Custer. “People tip all the time in this country,” he says as he waits to buy a small hunting rifle. “The problem is that everyone stands around saying ‘gimme, gimme, gimme.’”

Loyd Thomsen, the owner of the gun store, predicts that businesses will pass on the costs of a wage hike to customers. “In a lot of places it’s going to be reflective of higher prices, especially in small towns,” he says.

Thomsen is a proud backer of Mike Rounds, the GOP candidate for Senate, who opposes the wage hike as well. As governor, Rounds actually proposed and successfully passed the state’s last minimum wage increase in 2007, but says he opposes this increase because it’s indexed to inflation. (Republican Senate candidates in Alaska and Arkansas, by contrast, are supporting their states’ proposed wage increases.)

“It’s a forever government mandate,” says Shawn Lyons of the South Dakota Retailers Association, which is leading a coalition of business groups to fight the initiative. The group argues that “hundreds of jobs in the state” would also be lost. (The South Dakota Budget and Policy Institute, a non-partisan research group, estimates the initiative would cost an estimated 357 low-wage jobs.) Motivated employees should get raises “through merit and effort,” not mandates, Lyons concludes. “Those that start at minimum wage don’t stay there.”

But low wages have been a chronic problem in South Dakota. Low unemployment and growth typically put upward pressure on wages, as employers need to compete to hire workers. There should be even more upward wage pressure these days in South Dakota, which now has to compete for a labor pool that’s increasingly headed to North Dakota’s booming oil fields.

That hasn’t happened: South Dakota’s average wages rank among the nation’s lowest. While the economy has grown, poverty has increased as well, and the state’s Native American community — 9% of the total population — has especially lagged behind. More than half of Native Americans in Rapid City live below the poverty line, making it one of the most concentrated pockets of Native American poverty in the country.

“South Dakota’s always been behind, always behind,” says Larry Gonzalez, 57, waiting for the pow-wow to start at the Lakota Community Homes, a low-income housing development in northern Rapid City. “All my life, we’re always behind.”

His brother Leonard, 60, thinks a minimum wage hike would be a good place to start. “We need it. There’s nothing to protect the laborers and employees in South Dakota,” he says. While union membership is declining nationwide, unions historically have had even less clout in South Dakota, an early adopter of Right to Work laws that limit unions’ ability to compel workers to pay membership dues.

Low wages have also made it hard for the state to hang onto talent, the elder Gonzalez adds. “All the smart people, they leave the state, they make their money, then they come back,” he says. ‘

But it’s unclear whether a $1.25 wage hike would be enough to keep them here.

Certainly, there’s more work to be found in Rapid City than in the Pine Ridge Reservation an hour south, where unemployment tops 80%. That’s what prompted 34-year-old Lisa Iron Cloud and her husband Arlo to move from Wounded Knee to the city. Her dream is to open up her own store and teach sewing classes, so she recently applied for a job working retail at a local fabric store. But when she asked how much the job paid, and she was crestfallen when they told her minimum wage.

“You can’t do it — you just can’t do it,” says Iron Cloud.

“She really wanted it too,” her husband says, picking up their youngest child, three-month old Arlo Junior.

It wouldn’t be worth the cost of child care for her four kids, she explains. “You can’t get anything done on minimum wage.” But she’s also not sure an increase to $8.50 would be enough, either. “I don’t know that would make a difference,” she says.