FERGUSON, Missouri— Just days after 18-year-old Michael Brown was killed in a hail of police bullets, Joshua Williams found himself facing off with a phalanx of heavily-armed officers.

Williams joined the swarm of angry protesters who, in the wake of the teen’s death, took over the streets not far from the scene of the killing. They chanted and yelled and hoisted protest signs in the air. The police responded with snipers positioned on top of armored vehicles and a heavy deployment of officers, many with automatic rifles slung over their shoulders.

When someone from the crowd threw a rock or a bottle, the officers fired rubber bullets and tear gas into the crowd of overwhelmingly peaceful protesters.

During one emotionally raw moment, Williams, also 18, screamed at officers until his eyes were red and wet. Beads of sweat bubbled from his brow and his body grew tense. His voice strained under the shrill of pain swelling from his throat.

As he stepped closer and closer to the police line, a young pastor, Willis Johnson, wrapped Williams in a hug and pleaded with him to calm down. Williams broke down in the older man’s arms and a single tear tumbled down each of their cheeks.

“I just felt like they were trying to get over on us, trying to push us so that we’d react,” Williams told msnbc on a recent afternoon, weeks after that emotional day. “I was really upset. I saw children, little kids getting tear gassed and stuff. I just couldn’t take it.”

Like hundreds of other young people in Ferguson, many of whom have born the weight of a litany of alleged and frequent abuses residents say police have heaped upon the city’s black majority, Williams has found himself thrust into the heart of the city’s protests and civic action sparked by Brown’s death. Williams said he was initially spurred by his mother to take action.

“She was like, it’s B.S. and someone needs to stand up. So I stood up,” said Williams. “I was just like, another police officer killed a black man and they tried to get away with it. I had to get up and say enough is enough. And I’ve been out here every day since.”

On most days Williams, a recent high school graduate, takes up position with other protesters across from the Ferguson police department. But he also attends various meetings pulled together by a growing network of activists and organizers. He said he hasn’t missed a single day of marching, protesting or meetings.

%22I%20was%20really%20upset.%20I%20saw%20children%2C%20little%20kids%20getting%20tear%20gassed%20and%20stuff.%20I%20just%20couldn%E2%80%99t%20take%20it.%22′

“What energizes me are the people out here every day. People are out here sleeping in tents on sidewalks, protesting every day to get justice for Lesley McSpadden and her son,” Williams said, referring to Brown’s mother.

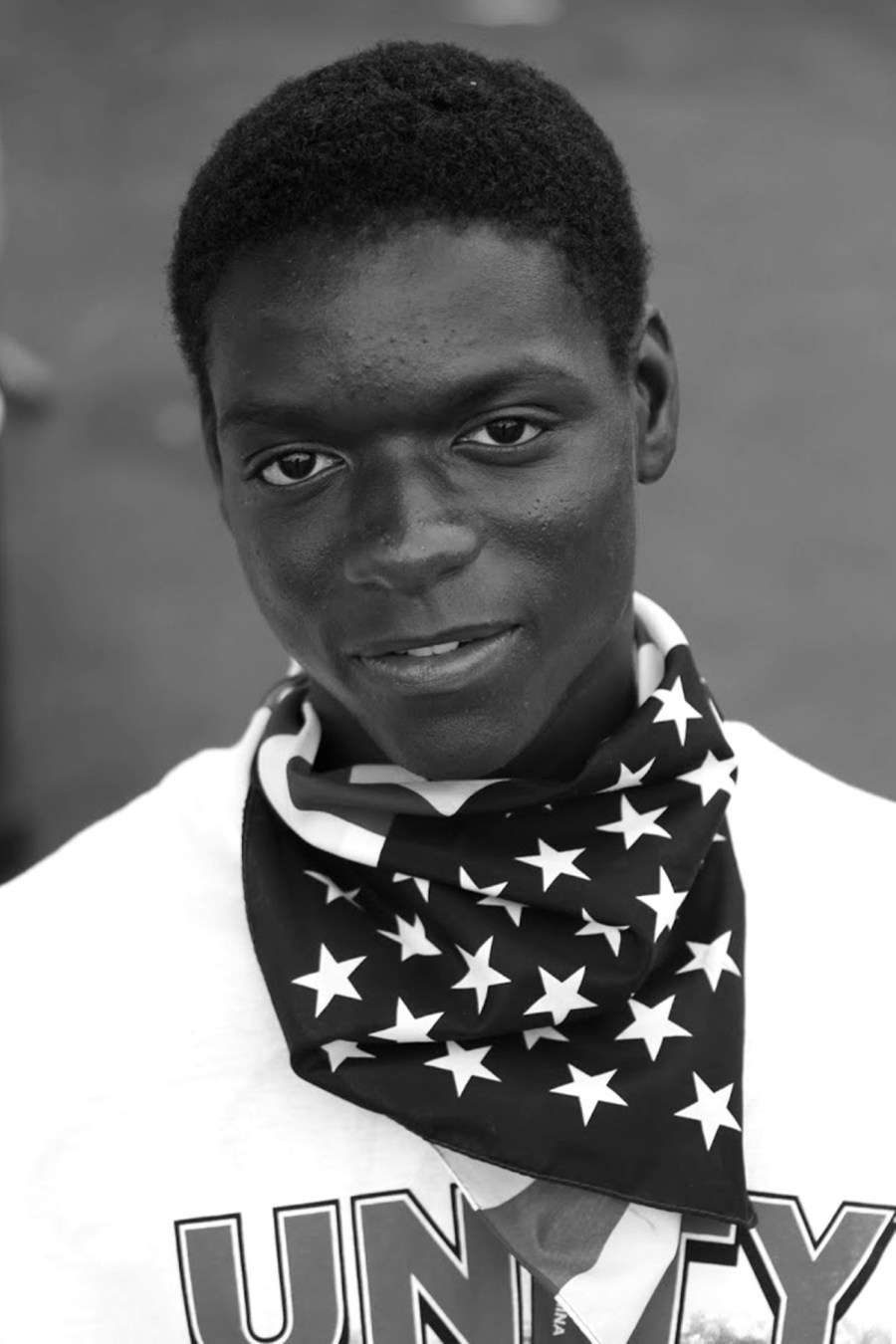

Brown, tall and lanky, Williams often has an American flag bandana tied around his neck. He’s gotten particularly comfortable handling a megaphone and riling up fellow protesters. On Tuesday night, during an at times raucous City Council meeting— the first since the shooting— Williams was among those who lined up to question, berate and at times belittle city leaders, nearly all of whom are white.

“I don’t know if most people will get over this or want to get over this,” Williams said, sitting across from the police station earlier this week. “I think we can be better if we can all come together. We might have to come together and show that we can work together and overthrow the system. But we have to come together as one and show them we can be peaceful, that we can do this. If not they’re going to just want us to act up so they can pull out their toys on us again.”

Before Brown’s death, Williams said he wasn’t really engaged in activism or any kind of civic action. He was a typical teenager, who one day hopes to become a professional dog trainer.

Alene Williams (no relation), who calls herself the younger Williams’ “protest mom,” said she couldn’t be prouder of all the young people who have fought tooth-and-nail to keep the call of justice for Mike Brown alive.

“It makes me feel proud because he could have been that child that got shot. There are a lot of faces that could have been laying in the street. But it could have been him but now he’s out here fighting for justice,” she said. “If we stop, even if we get justice in this case, why stop there. It could happen again here or anywhere else. What about Eric Garner? What about Trayvon Martin? They still haven’t gotten justice.”

Joshua Williams said much has changed since the early days of protest. Those were filled with violent clashes with police, some looting and some businesses being broken into or burned down. “It’s like a serious shift from when all that stuff happened and I really think some good is going to come from the bad,” he said.

From the protests and the national media attention drawn to Ferguson, a suburb of St. Louis with a population of about 21,000 residents, a light has been shone down on the myriad, systematic ways in which advocates say many of the city’s poor and black residents have been treated unfairly. The Department of Justice has launched a parallel investigation into Brown’s case and said it is investigating the entire Ferguson police department for past allegations of civil rights violations.