We already knew that Wall Street banks were too big to fail. But are they also too big for the Obama administration to prosecute?

On Tuesday, the government announced it wouldn’t charge HSBC, the British-based megabank accused of enabling money laundering by Mexican drug cartels, among other crimes. Instead, it’ll require HSBC pay a fine of roughly $1.9 billion and improve its compliance measures. That’s the largest fine ever for such a case, but as The Guardian’s Nils Pratley noted, it represents about four weeks’ worth of pre-tax profits for the banking behemoth, which made almost $22 billion last year.

HSBC allowed Mexican drug cartels to launder dirty money through the U.S. financial system, and worked with Saudi Arabian banks linked to terror groups. At times, the drug traffickers deposited hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash, in a single day, into just one account—using boxes specifically designed to slide neatly under HSBC’s teller windows. And the bank ignored warnings from regulators to beef up its controls, a Senate report released in July found.

So why no criminal charges? Because, according to the Department of Justice, that might jeopardize the bank’s existence in the U.S., potentially destabilizing the global financial system.

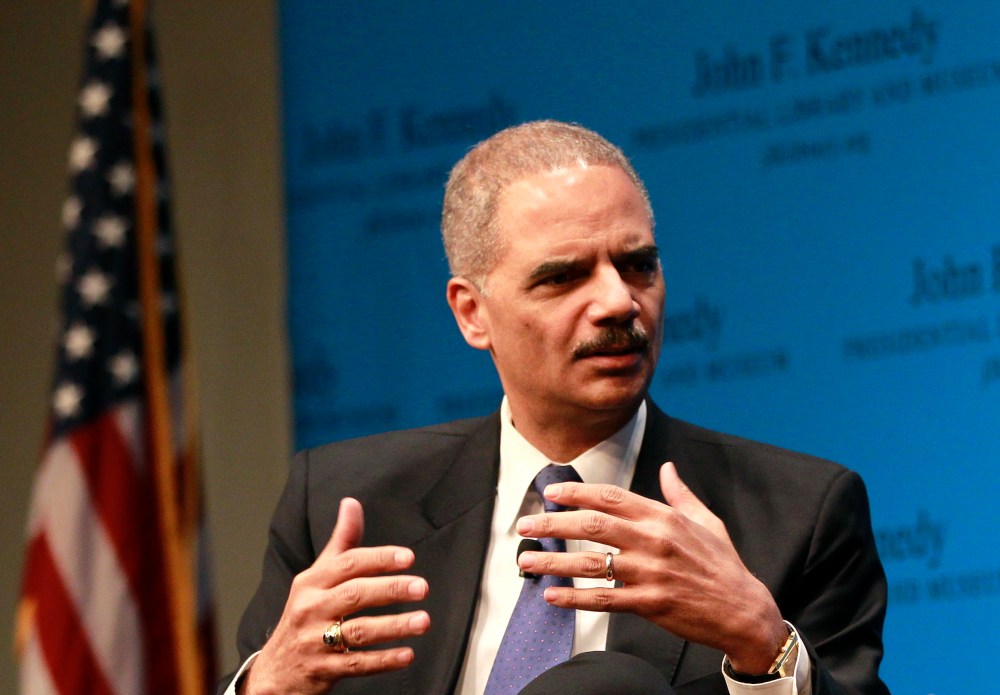

“If you prosecute one of the largest banks in the world, do you risk that people will lose jobs, other financial institutions and other parties will leave the bank, and there will be some kind of event in the world economy?” Lanny Breuer, the head of the Justice Department’s criminal division, asked in an interview with The Washington Post.

The argument is eerily similar to the one made by Bush and Obama administration officials to explain why taxpayers needed to bail out Wall Street at all costs. In that case, critics charged, the threat of a systemic collapse allowed the banks to hold taxpayers hostage. In this, it’s allowing at least one to hold the justice system hostage.

Some experts say Breuer’s excuse doesn’t even hold water. A conviction against HSBC itself could potentially—though not definitely—cause the bank to lose its license to operate in the U.S., Jimmy Gurulé, a law professor at Notre Dame and a former assistant U.S. Attorney General, explained. But prosecuting individual HSBC officials accused of wrong-doing would have little larger impact.

“That argument does not explain at all why the Department of Justice has been unwilling to go after individual bank officials,” Gurulé said. “That’s not going to affect HSBC’s ability to do business in the United States.”

“Here we have serious crimes that justify a $1.9 billion penalty,” Gurulé continued. “And yet no one is held personally criminally responsible. What’s wrong with that picture?”

“I don’t think the Department of Justice has come clean,” he added. “I don’t think they have explained or justified their conduct.”

Jack Blum, a former special counsel for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and an expert in money laundering and financial crimes, was just as blunt. “What do you have to do to be prosecuted?” he asked in an interview with The Washington Post. “They have crossed every bright line in bank compliance. When is there an offense that’s bad enough for a big bank to be prosecuted?”

What does explain the department’s reluctance to prosecute? Gurulé noted that the Senate report had turned up evidence of shocking regulatory failures by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the government agency responsible for stopping money laundering by banks. He speculated that a prosecution could have embarrassed the Feds.