For many Americans, the phrase “political action committee” conjures up images of a bunch of guys in suits shelling out big money to buy influence, power, and negative campaign ads. Definitely not conjured is the image of two 20-somethings working out of their tiny apartments to propel young progressives — especially minorities — into state office.

But Poy Winichakul and Luke Squire , both 25, are trying to do just that, starting with the 2014 midterm elections. Last year, the pair left behind stable jobs and comfortable salaries to start the political action committee Launch Progress, with the goal of increasing the number of young progressives in public office. They’re sick and tired of the same old, white men failing to get anything done in state legislatures across the country, they say — and they’re determined to increase the diversity of age, race, and gender in America’s governing bodies. It surely won’t be easy — but the pair seem determined to succeed.

“It’s definitely a struggle,” acknowledged Winichakul from her small, one-bedroom apartment where a giant American flag with a peace sign instead of stars hangs from her wall. The apartment, in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, also serves as a Launch Progress office.

Winichakul previously worked at the Brennan Center for Justice, while Squire –the two met at Oberlin College — was a consultant at Booz Allen Hamilton, and later a research coordinator for Democratic Sen. Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota. “In many ways we’re just like our candidates. We’re taking this big risk but we know it’s the most important thing we could be doing right now,” Winichakul said.

This election cycle, Launch Progress endorsed 10 candidates in Ohio, Michigan and North Carolina who are running for state Senate or House seats. There are strict contribution limits that PACs can give to candidates in those states ($12,155 in Ohio, $10,000 in Michigan and $5,000 in North Carolina), but Launch Progress isn’t exactly smashing into those ceilings yet. Since its first fundraiser in April, Launch Progress has raised about $11,500.

But, as Winichakul explained, Launch Progress isn’t just there to “throw money at candidates,” but to provide a network connecting candidates with the 40 people on the group’s advisory board—from lawyers to community organizers to experts in areas like education and healthcare—to help with their campaigns. Board members have helped develop policy papers, campaign plans, and speechwriting — and they ultimately decide if the PAC will endorse a young candidate (based on their stances on a number of issues, including individual liberty, affordable education, economic, social and gender equality, and the environment). Launch Progress is as much about providing young progressive candidates with the political expertise they lack as it is about bolstering their war chests.

Launch Progress, Squire explained, began over glasses of scotch the night of Obama’s 2013 inauguration. Yes, Obama had been propelled into a second term and progressive icon Elizabeth Warren had won a Senate seat in Massachusetts. “But there was a realization of how bad things had become — the inability of Congress to pass anything and it seemed like few young people were entering public office,” which ultimately starts at the local level, said Squire.

“’What’s stopping you and me from doing something?” Squire recounted Winichakul asking him. “We thought we’d go ahead and try it out. We had no families to support and we had some money saved. We wanted to see if the idea would catch fire.”

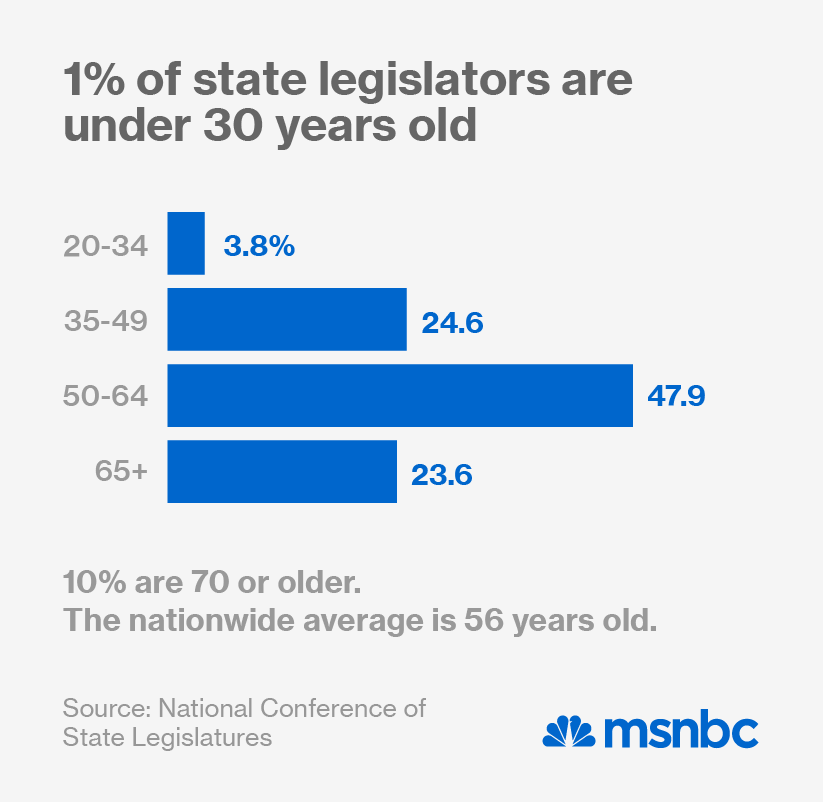

Launch Progress will have an uphill climb. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 3.8% of the 7,382 legislative seats across the country are held by people between the ages of 20 and 34. If you’re looking at state lawmakers under the age of 30, the percentage drops to 1%. The average age of a state legislator nationwide is 56 years old.

The United States Congress is even older and grayer. There are no senators under age 40 (the Constitution requires senators to be at least 30). In the House, there are just seven lawmakers who are 35 or younger (the Constitution requires members of the House to be at least 25).

“There are just a lot of barriers into entry for young people pursuing office,” said Andrew Gillum, the executive director of the Young Elected Officials Network, a non-profit organization that helps support already elected officials who are 35 and under. “As a byproduct of being young, they have fewer relationships with people who can give them money. They are often in places where there are already established political machines and systems they have not been involved with.”

Gillum, a 35-year-old city council member in Tallahassee, would know. He was elected at the age of 23. Besides not having a rolodex of contacts, many young people come out of college with significant debt. That, paired with a job involving long hours, little pay, and oftentimes a second job to pay the bills, isn’t always appealing, he said.

Peter Levine, the director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University, said many young people are simply turned off by electoral politics — they are disgusted by what they see as gridlock, negative advertising and the increasing role of money in campaigns.