Stairs are for climbing or descending, but for Marvin Bolton they also are a place to rest, eat and sleep.

The 61-year-old homeless man with a graying goatee spends most of his evenings and nights in the stairwell of a building in New York’s St. Nicholas housing project, sitting on the steps or reclining on the cement landing on the ninth-floor of the 14-story building. Sometimes he does both, laying a piece of cardboard on a step to sit on, then putting a newspaper down on another step where he can place his elbow and rest his nearly toothless head in his hand, surrounded by dirty white walls and bathed in bright florescent light.

All his earthly possessions are within reach: a toothbrush, his cellphone, a couple shirts and a few pairs of pants, three coats, a hat and gloves and a suitcase.

The stairwell is sometimes noisy and is home to the occasional cockroach, but it’s a warm refuge from New York’s cruel winter. Marvin avoids homeless shelters because he thinks they’re unsafe and unhealthy. They also stress him out, making the cravings for the crack cocaine and heroin that have landed him in jail many times over the last 40 years even more intense.

RELATED: Geography of Poverty: A journey through forgotten America

Marvin is just one of 60,000 homeless people in the city and, as a single black man with a drug problem, in many ways typifies them. But by refusing to take advantage of the city’s shelter system, he’s also one of the city’s most vulnerable residents.

“Life is hard because of the things that I have to go through, just trying to survive, you know, trying to put food on the table so to speak,” he says. “Winter makes a lot of things rough for me… It’s too cold. I don’t have the proper gear… Being out here, I can get sick from this type of weather. I’m taking a lot of chances, you know?”

Introspective, but not one to dwell on the negative, Marvin has spent his first winter without a real roof over his head developing a strategy for survival: He layers pants and sweaters to combat the cold, tells time by whether certain stores are open or not and checks the weather report at a laundromat, so he doesn’t get caught out in a storm.

He often spends entire days on the go. Until recently, that meant pushing a shopping cart that he referred to as “the Cadillac” around an area extending roughly 30 square blocks in central Harlem, clomping along on a bad ankle and singing as he scavenged for items in garbage bins that he could resell to supplement his $720 monthly Supplemental Security Income payment. But after his cart was stolen in mid-March, he has a much harder time collecting cast-off items.

From those conversations emerged nine life lessons, hard-won epiphanies from Marvin’s journey that shed light on what you can’t know about survival when you have a home:

1. There is a day things finally catch up with you

Rose Dunn, 64, Marvin’s only sibling, remembers her younger brother, nicknamed Beanie, as someone who brought home high marks in school. He also was an overachiever when it came to basketball, baseball and even bicycle racing, and a talented artist and musician who was their mother’s favorite, she says.

Because their father was not often home, their mom, Emma,often worked two jobs – as an administrator in the garment district and as a receptionist for a book publishing company. Despite her long hours, their home in the St. Nicholas Houses – just across the street from the stairwell that Marvin now calls home — was run with love and a firm hand.

Dunn will never forget the day in 1973 when everything changed.

“I got off the train from work,” she said. “I hadn’t even gotten to 131st Street when people that knew me from the projects said, ‘Rose, I think they just picked up Beanie.’ I was thinking, ‘Who picked him up?’ and finally someone said, ‘He just sold some narcotics to an undercover cop and they busted him.’”

Dunn had an idea that her brother had been selling drugs, but said that the family was still shocked. They had not known how serious things had become.

“It all started because my father drifted away from home,” she said. “We used to come home to hot meals and do our homework. But as we got older and noticed the drifting of my father and saw how that meant our mom had to get a second job, Marvin wanted to help out. I guess the quick money was out on the streets and eventually we noticed Beanie making money and people knocking on the door at all hours of the night and we figured out what he was into.”

Forty years later, Marvin willingly acknowledges that his decision to get involved with drugs is the biggest reason he no longer has a home.

2. You never sleep soundly

As the temperature drops and night falls, Marvin sets up camp in the ninth-floor stairwell.

Even as he gets himself situated and relaxes for the first time all day, Marvin remains attentive, listening for police officers who periodically patrol the building and may ask him to move along.

He often heads out in the early evening to search the garbage bins of nearby residents in search of items he can either resell or give to his neighbors, which he must find before the garbage is picked up in the morning. Sometimes, he doesn’t get back until 1 or 2 a.m.

“I think I do more walking than sleeping,” he said. “I’m up most of the night, you know. But I get some type of rest.”

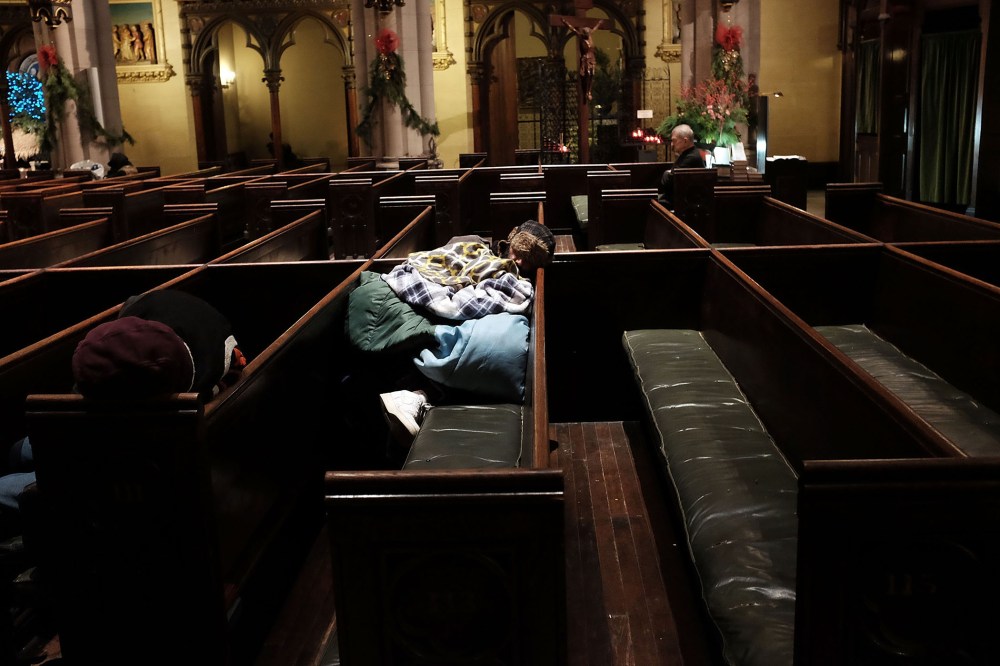

3. People will feed and clothe you

Between Harlem’s Salem United Methodist Church and the Metropolitan Baptist Church, Marvin can enjoy a warm midday meal each day and pick up some groceries and clothes weekly.

The meal at one of the churches is often Marvin’s only hot meal except for the coffee and pastries offered in the morning at his drug treatment program, where he receives methadone that keeps his craving for heroin in check. The churches also provide bathrooms, where Marvin can clean up a bit for the day.

4. Still, you need to be charming

Building tenants unlock the door for Marvin so that he can access the stairwell where he sleeps, often in response to text messages. Others check on Marvin to offer him a pillow and blanket at night or a warm plate of food. And old friends give him odd jobs or offer him a few dollars to help him get by.

“Even though he has his difficulties and hardships, he’s still an asset to the community in his own way,” friend and neighbor Bernard B. said. “Sometimes I’ll be coming in, me and my wife, with groceries and he will help me and I help him the way I can help him. It’s not like he’s looking at me as a way of living.”

For his part, Marvin does whatever he can to help his neighbors, including bringing them usable household items he scavenges and perishable groceries he receives.

5. You can make money from other people’s garbage