In the end it may have been Kalief Browder’s short life and tragic death that finally freed the very young from isolation in American prison cages. At 16, he was accused of stealing a backpack and sent to New York’s infamous Rikers Island to await trial. During his stay he was brutalized by guards and inmates alike and spent nearly two years in solitary confinement.

A few years after being incarcerated, he was released — without a trial. From the day he stepped foot back into freedom, Browder’s life was a nightmare, unable to shake the terror of what he’d experienced behind bars and in that dark box, locked down for up to 23 hours a day. He started going to community college but had trouble staying in class. He tried killing himself on multiple occasions, but each time survived, ending up in a hospital psych ward.

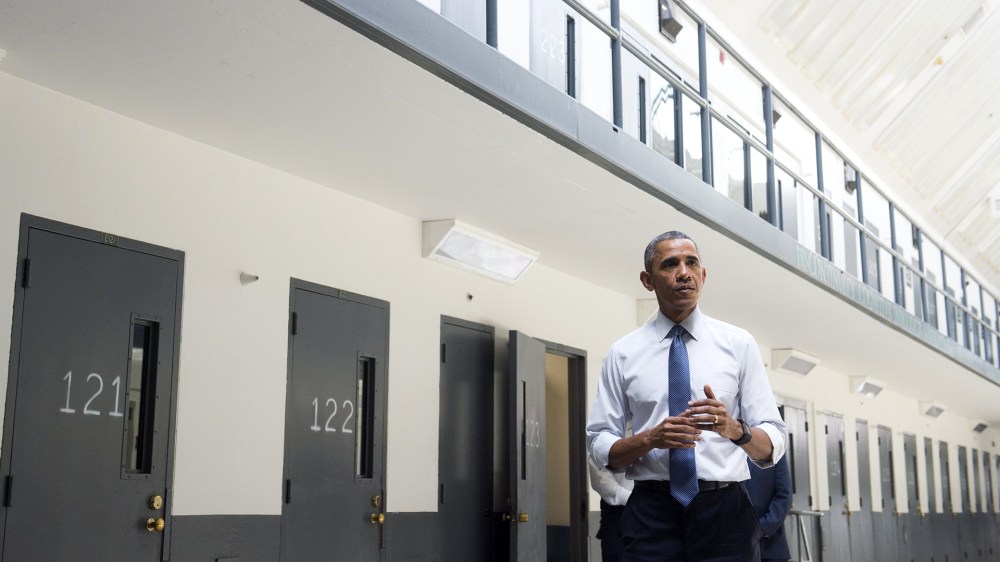

RELATED: Obama to end solitary for juveniles in federal prisons

Then one day last summer, Browder, then 22, pushed an air-conditioning unit out of a second floor window at his parent’s home in the Bronx. He tied a cord around his neck and pushed himself through the window feet first.

Browder’s life, death and struggles after being released from jail sparked the kindling of criminal justice reform that had been simmering for years, drawing together wide bi-partisan support for cinching the pipeline to prison that has funneled through it countless young men and women from poor communities across the country.

On Monday, when Obama called for an end to the practice of solitary confinement for juveniles, he did so evoking Browder’s name.

“Solitary confinement gained popularity in the United States in the early 1800s, and the rationale for its use has varied over time. Today, it’s increasingly overused on people such as Kalief, with heartbreaking results — which is why my administration is taking steps to address this problem,” Obama wrote in the Washington Post, announcing the ban.

Moved to action by the horror stories of trauma and abuse suffered by juveniles locked up in isolation, Obama sought to continue laying the groundwork for broad criminal justice reform, but also, perhaps, to solidify his legacy as a president that firmly pressed his thumb to the scale of social inequity.

In a series of executive actions, Obama this week sought to taper a long and controversial era of crude law enforcement tools employed en masse during the so-called War on Drugs, which ushered in an era in mass incarceration.

His move on Monday to end solitary confinement of young inmates in federal prison is limited given the relatively low number of juveniles in federal custody, but many who’ve been advocating on behalf of youthful offenders hope the ban will push states to enact similar bans in their prisons, which house the vast majority of juvenile inmates.

The White House estimates that 10,000 inmates would be covered under the new executive actions, representing just a small fraction of the 100,000 prisoners held in solitary confinement on any given day.

As recently as 2012 there were more than 57,000 juvenile offenders locked away in jails and prisons across the country, according to the Justice Department. Many of these juveniles — under the age of 18 — are held in solitary confinement, alone and often in small cells with limited natural light and limited human contact for up to 22 hours a day.

RELATED: Juveniles sentenced to life in prison given a second chance

The long-term emotional and psychological effects can be damning on a hardened adult prisoner, let alone a teenager whose psyche is still being shaped.

“Research suggests that solitary confinement has the potential to lead to devastating, lasting psychological consequences,” Obama said. “It has been linked to depression, alienation, withdrawal, a reduced ability to interact with others and the potential for violent behavior. Some studies indicate that it can worsen existing mental illnesses and even trigger new ones.”

For years the United States stood out in its acceptance of solitary confinement for juveniles, a practice that the United Nation’s has condemned as torture, and a practice that is widely prohibited around the world.

Banning isolation for the most vulnerable within prison populations— including juveniles and the mentally ill— has been years in the making, buoyed by bipartisan support of reform in Congress and a new willingness to rethink how even the most hardened of juveniles should be punished.

“President Obama’s decision to ban solitary confinement for youth of 16 and 17 puts a spotlight on what we know to be true: juveniles are not adults and should not be treated like adults in the criminal justice system,” said Jennifer March, executive director of the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York.

For some, reform is seen as a moral obligation, while for others it’s a fiscal one. As states in recent years have faced steep budget shortfalls, housing and feeding low-level offenders for long sentences simply became too costly.

Some states have already taken up the cause, though, while at times pushed in a corner. A pair of lawsuits in Oregon and Illinois have prompted prison officials to exclude mentally ill inmates from facing isolation. New York last month reached a $62 million settlement with the ACLU and agreed to dramatically reduce its solitary confinement population and cut the maximum amount of time inmates can spend in isolation. Ohio reached an agreement with the DOJ in 2014 after federal investigators found that at least 229 boys with mental-health problems were kept in solitary confinement for almost 60,000 hours over a six-month period.

“The president is leading the way for other states to follow suit,” said Alida Merlo, an expert in juvenile justice policy and professor at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania. “It’s very odd to think that in 2016, we’re debating if we should be banning solitary confinement for children. It shouldn’t have to be on the agenda.”

%22Juveniles%20are%20not%20adults%20and%20should%20not%20be%20treated%20like%20adults%20in%20the%20criminal%20justice%20system.%22′

Public shock and outrage over Browder’s death spanned the political spectrum, setting the stage for criminal justice reform to emerge as a central pillar to the issues shaping the 2016 presidential race. Out on the campaign trail, Republican Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky incorporated Browder’s story into his stump speech. Other candidates have focused broadly to overhaul a system that disproportionately impact communities of color.

The timing of Obama’s push for criminal justice reform also pairs with historic efforts in Congress to adopt bi-partisan legislation before the end of the year. A bill to reduce prison sentences for nonviolent offenders has the crucial backing of key players from both parties, making hopes of achieving significant reform more than just a pipe dream.

There’s still a minefield of obstacles ahead that Congress will have to navigate with deft footing in order to pass meaningful reform. Rather than wait for Congress, Obama’s measures this week go even further than legislative proposals on solitary confinement for juveniles.

The drive to treat juveniles differently in the system now extends to all branches of the federal government. Obama’s announcement comes on the same day that the Supreme Court decided that convicted killers sentenced to life in prison as juveniles must have the chance to argue for parole.

RELATED: Recent prisoners navigate an unfamiliar world