As North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton and many other opponents of LGBT civil rights protections see it, policies barring discrimination on the basis of gender identity pose a serious threat when it comes to the bathroom. But if that were the case, no city would be more unsafe than Minneapolis, where transgender people have been protected from discrimination in bathrooms and other public accommodations for more than four decades.

The reality is, of course, quite different. In Minneapolis, as in more than 200 cities and 18 states that have since adopted similar protections, no increase in bathroom-related violence has followed; no person has ever been sexually assaulted or harassed in a bathroom by someone who is transgender; and no policy protecting LGBT people has ever provided legal cover to someone pretending to be transgender in order to attack another person in the bathroom. No policy ever would.

Yet McCrory, Paxton and others continue to stoke fears about the privacy and security of women and girls in the bathroom — concerns that, according to activists and aldermen responsible for the passage of Minneapolis’ nondiscrimination ordinance in 1975, never once came up in that first legislative step for transgender rights.

“No, there was none of that,” said Louis DeMars, who served as president of the Minneapolis City Council during the time it adopted transgender protections, of today’s brand of bathroom-based hysteria.

“There were plenty of people who thought we were being foolish and testified against it,” DeMars continued. “But I don’t recall a large group opposed. It may be fair to say that the general public didn’t understand what we were talking about back then anyway.”

Though parts of it remain a mystery, suffice it to say that the story of how Minneapolis became the first city in the country to include transgender people in its civil rights ordinance is not a dramatic one. Few newspaper articles from that time mention anything about it, and many of the activists involved in its passage have either since passed away or become hazy on the details.

Still, the sheer length of time that Minneapolis’ ordinance has been on the books serves as perhaps the strongest piece of evidence to date refuting the widely circulated charge that similar LGBT protections somehow jeopardize the safety of others. From what those credited with the ordinance’s existence can remember, bathrooms — as a potential breeding ground for sexual assault or harassment — belong to a younger generation’s anti-LGBT playbook.

***

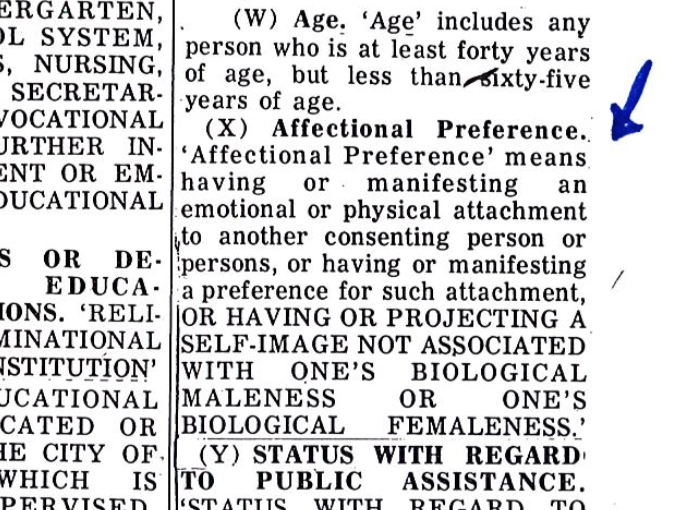

In December 1975, Minneapolis quietly adopted an ordinance barring discrimination on the basis of “having or projecting a self-image not associated with one’s biological maleness or one’s biological femaleness.”

The policy was the first in the nation to specifically protect LGBT people in employment, labor union membership, property ownership, property rental, enrollment in schools and use of public services and accommodations (like bathrooms). Yet the measure drew little notice, passing in what The Policy Insitute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force labeled “a general flurry of progressive legislation enacted just before a newly elected, more conservative mayor started his term.”

Minneapolis was, at the time, a burgeoning hotbed of LGBT activism and one of only two cities in the country then offering sex reassignment surgery, according Andrea Jenkins, head of the University of Minnesota’s Transgender Oral History Project. But that didn’t mean the city was drawing massive numbers of transgender people to the area who were then, in turn, pressuring the city council for legal protections.

Rather, as former alderman DeMars remembers it, the effort to pass transgender protections was tacked onto, and largely overshadowed by, a far more controversial fight at the time for gay rights and same-sex marriage.

“It all kind of started in 1971 with a fellow by the name of Jack Baker,” said DeMars, recalling one of the earliest advocates for marriage equality.

That year, Baker and his now-husband, Michael McConnell, obtained a marriage license in Mankato, Minnesota, in what they maintain was the country’s first lawful same-sex marriage. (An earlier attempt by the couple to apply for a marriage license was denied, sparking a lawsuit that went all the way up to the Supreme Court. The justices dismissed their case “for want of a substantial federal question” — a decision that was overruled last year in the landmark case of Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized nationwide marriage equality.)

The year 1971 was also when Baker won his bid to become the country’s first openly gay student-body president when he was elected as a law student at the University of Minnesota. Walter Cronkite reported the news on network television.

“Because of him and the publicity surrounding him, [gay rights] became very visible,” DeMars said.

Baker’s husband, McConnell, also became involved in gay rights activism around that time. After seeing his job offer rescinded by the University of Minnesota following the attention his marriage application garnered, McConnell sued in federal court, where he ultimately lost. “Homosexuals,” concluded the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals in 1971, had no right “to foist tacit approval of this socially repugnant concept upon his employer.”

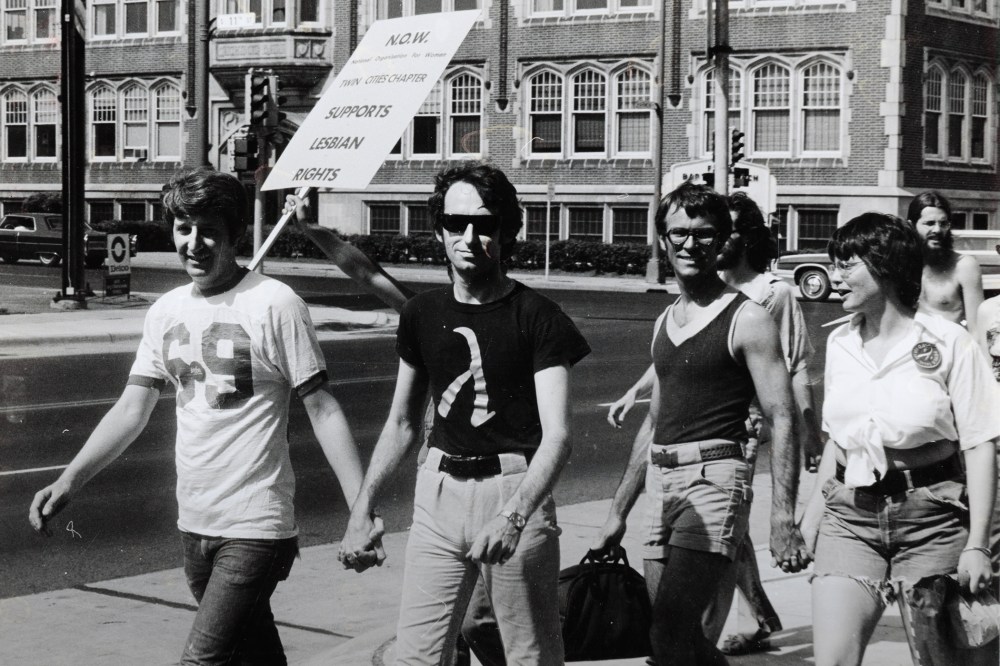

Down but not out, McConnell decided to start one of the country’s earliest gay community centers, called Gay House, and focused his attention on getting Minneapolis’ Pride Parade off the ground.

“As we got Gay House going, it acted as a spawn in the community for other social service groups,” said McConnell. “By this time, people were starting to talk about protecting gay rights.”

Led by Steve Endean, who went on to found the Human Rights Campaign, this growing network of gay rights activists began to solicit support from Minneapolis aldermen for a so-called “gay rights ordinance.” And in March 1974, their efforts paid off: The city council voted 10-0 to ban discrimination on the basis of “affectional or sexual preference.”

According to McConnell, the peculiar phrase “affectional preference” was meant to elevate gay life beyond purely sexual behavior.

“In a sex-phobic culture, the minute you start to define yourself as a sexual creature, people stop listening to you,” he said. “That’s why we talked about love, commitment and marriage.”