There have been better times to be a public sector worker. Over the past several years, government employees have been buffeted by across-the-board sequestration cuts, a years-long federal pay freeze, unpaid furloughs, benefit cuts and threats to the relative strength of their labor unions. But most of all, government employees have been deluged by pink slips.

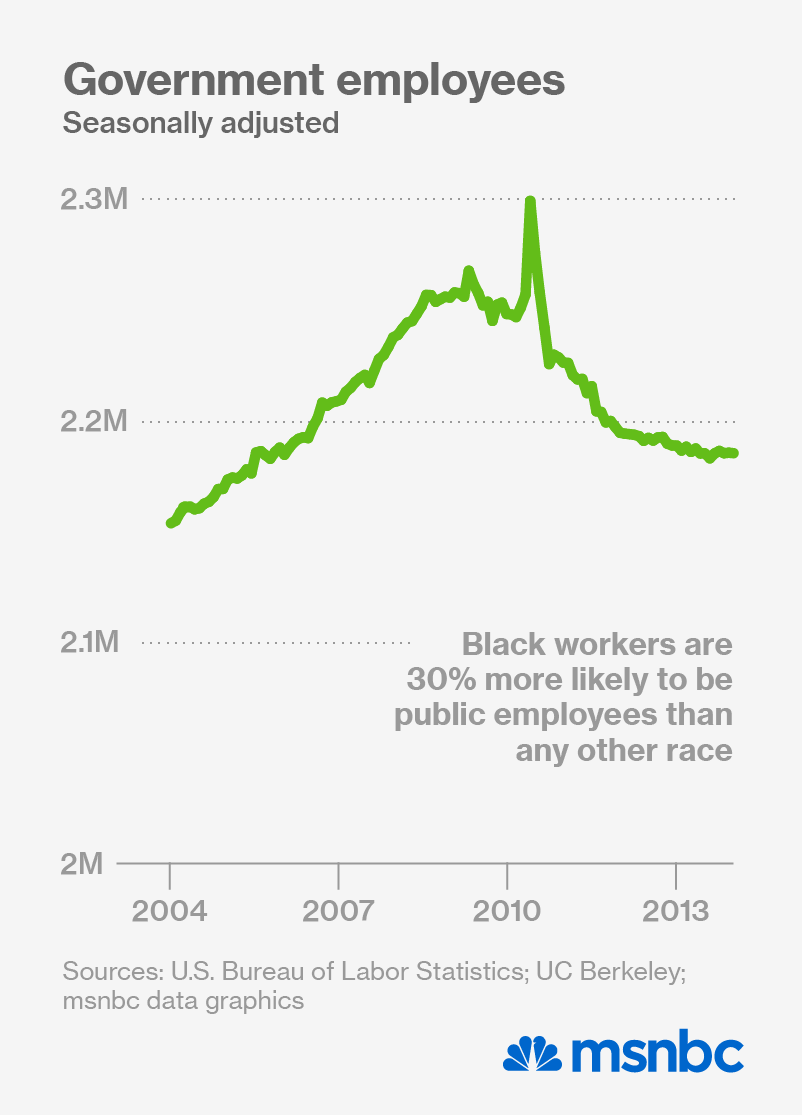

Aggressive budget-cutting in the aftermath of the recession has resulted in public sector layoffs on an unprecedented scale. By mid-2012, the public sector had shed more than 600,000 jobs, “the largest decrease in any sector since the recovery began in July 2009,” according to the Brookings Institution. The flood of terminations slowed to a trickle in 2013, but it didn’t stop entirely. And while the most recent jobs report offered some hope that public sector jobs may finally be coming back, it will be a long time before the government employs as many people as it did before the financial collapse.

“They were taking a meat cleaver” to public sector employment, said William Rodgers, a professor of public policy at Rutgers University. And the result wasn’t just swelling unemployment or reduced government services: Mass firings in the public sector have also disproportionately affected black communities, inflaming America’s swollen racial income gap. One of the country’s key sources of living-wage employment for black workers is now being taken apart, piece by piece.

For decades before the Great Recession, public sector employment was one of the country’s sturdiest ladders into the middle class for African Americans. In part, that’s because the public sector has been stricter about policing workplace discrimination since the 1960s and 70s. As a result, research from the University of Georgia Department of Public Administration and Policy has found evidence [PDF] that women and black men in some states have been “pushed” into government employment by private sector wage discrimination. This may help to explain why black workers are now 30% more likely to be employed in the public sector than workers from any other ethnic group.

“By and large, you see that blacks in the public sector are paid better than blacks in the non-public sector,” said UC Berkeley labor economist Steven Pitts. In New Jersey, for example, a recent study [PDF] found that black public sector workers earned nearly twice as much on average as black private sector workers. And there are other advantages as well: Workers employed by the government tend to receive better health insurance and pensions, and are unionized at a significantly higher rate than private sector workers.

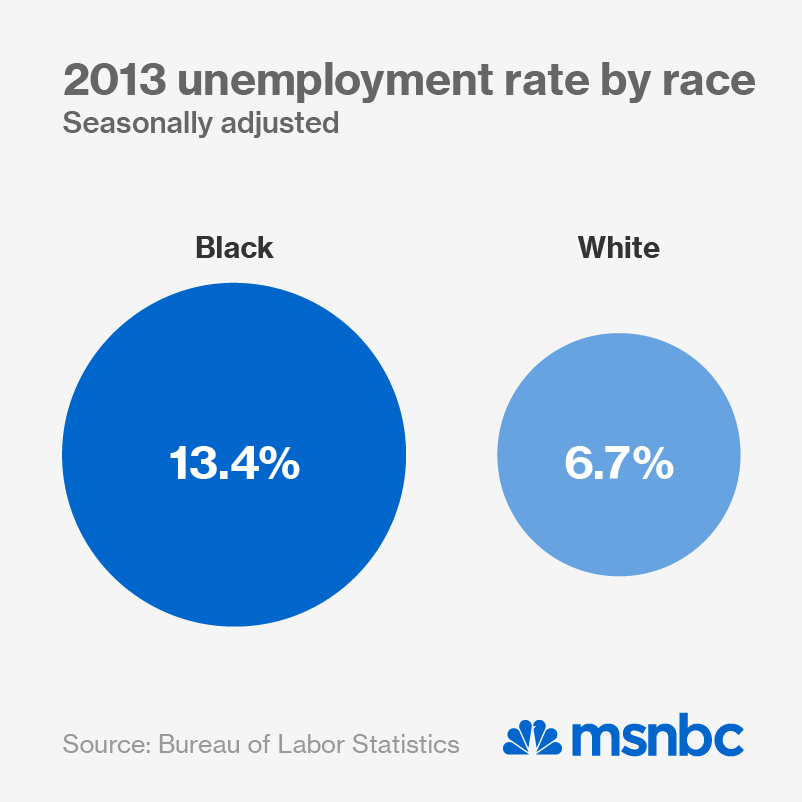

But post-recession government austerity has dramatically reshaped the landscape of public employment. Black workers aren’t the only population to be affected by widespread government layoffs, but they might be the most vulnerable. After all, median household income for African Americans tends to lag behind white income, and black unemployment is consistently twice as high as white unemployment. For black families, that means losing a solid middle-class job has the potential to be even more devastating.

“To the extent that unemployment itself is high in the black community and people are still able to eat, you’ll find oftentimes that people who have a government job — or any job — are supporting other members of the family as well,” Pitts told msnbc. When that one person loses that one job, the rest of the family suffers.

For Pitts, the problem comes down to ratios: In his words, “the nature of the disparate impact comes from the fact that blacks are disproportionate in the jobs themselves.” Even if the decisions about who to fire were colorblind, black communities would still face the worst consequences. But Rodgers’ research suggests it’s even worse than that.