CHICAGO— After Parrish Brown graduates from Walter Dyett High School this spring, it’s likely he’ll never set foot in that school building again. Not for a 10-year reunion or to catch up with former teachers or to admire the gleaming trophies inside the school’s display case.

Because if all goes according to the city’s plan, there soon will be no Walter Dyett High School to return to in Bronzeville, an historic African-American enclave on the city’s south side.

“They closed my elementary school and now they’re phasing out my high school. One day there’ll be nothing in my community to come back to,” said Brown, 17.

“Phasing-out” is a euphemism for slow death in a district that has become increasingly aggressive about closing public schools in poor and African-American neighborhoods.

Dyett is scheduled to close at the end of next school year, at which point, community groups say, there will be no other viable public high school in the neighborhood–essentially creating a “school desert.”

Mass school closings have become a growing trend in major cities across the country, including Philadelphia, New York City, Oakland and Detroit. But in Chicago, the school board has struck more broadly and with a heavier axe than any other school district in the country. For more than a decade the school district has been on a mission to close underperforming and underutilized schools, mostly in minority neighborhoods on the city’s south and west sides. Since 2001 the district has shuttered or phased-out about 150 schools, including 49 over this past summer. It was the largest single mass school closing in American history and affected more than 30,000 students who were either displaced or whose schools absorbed the massive spillover.

In Chicago and nationwide the school closings have destabilized tens of thousands of mostly African-American students. About 88% of the students affected by the Chicago closings are African-American, 10% are Latino and 94% come from low-income families.

Opponents of the closings say officials with Chicago Public Schools (CPS) and the school board have essentially sabotaged neighborhood schools by starving them of resources, claiming the mayor’s appointed school board has served as enforcers for the mayor’s pro-business agenda to privatize public education. As the district has been active in closing and defunding public schools, a flurry of new charter schools has sprung up across the city. Just last week, CPS proposed the addition of 21 new charter schools.

“They are choking these schools out and they know exactly what they are doing,” said Steven Guy, a member of the Local School Council at Dyett. “This slow death does more damage. It’s psychologically damaging to the children. We’ve already lost one generation, and we’re about to lose another.”

The closings were meant as a cost-cutting measure to buoy the beleaguered district, which is facing a budget deficit of nearly $1 billion. This school year CPS cut about $180 million from direct classroom spending and central office expenses, in addition to laying off nearly 2,000 teachers. Decades of population decline had left many of the city’s schools far below capacity, and the district sought to consolidate resources and students.

But some of the schools, as is the case with Dyett, are being phased out because of “chronic academic failure and the need for higher quality educational options for students,” according to CPS’s plan for the school. In the most recent round of state testing, only 6.5% of the school’s 11th graders met or exceeded state standards in reading, math and science, despite recent improvements in graduation and college acceptance rates.

Prior to this year’s school closings, CPS had closed, turned around or converted to charters or selective enrollment 20 area schools since 2001, according to a 2012 report by the University of Illinois at Chicago. Between 2005 and 2010, four high schools not far from Dyett were closed.

At the same time CPS began to financially disinvest in the school, leading to crucial programs being cut, including popular college preparatory programs.

“This is not about school choice. If it was really about providing us with choices, we’d have the choice to improve our neighborhood schools,” said Jitu Brown, the education organizer at the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization (no relation to Parrish Brown the high school senior). “When you shut down neighborhood schools you’re not providing choices, it’s displacement by force.”

‘School is their only stability’

At the start of last school year, more than 30,000 Chicago public school teachers went on strike, walking out as negotiations with the school board broke down and talks with Mayor Rahm Emanuel became increasingly terse. The strike was widely regarded as a win for teachers, albeit with concessions.

But in the year since the strike, the euphoria over the modest gains has faded, muted by what teachers and analysts describe as battles on all fronts. There were the school closings and the layoffs. And crippling budget cuts–so deep that teachers tell of having to buy toner for their classroom printers or purchasing toilet paper, as well as additional layoffs in schools already strapped for vital academic resources.

Dyett laid-off 16 teachers this year. The school is an extreme but not atypical example of the impact felt on individual schools and the students they serve, as the layoffs and budget cuts ripple far beyond the classroom.

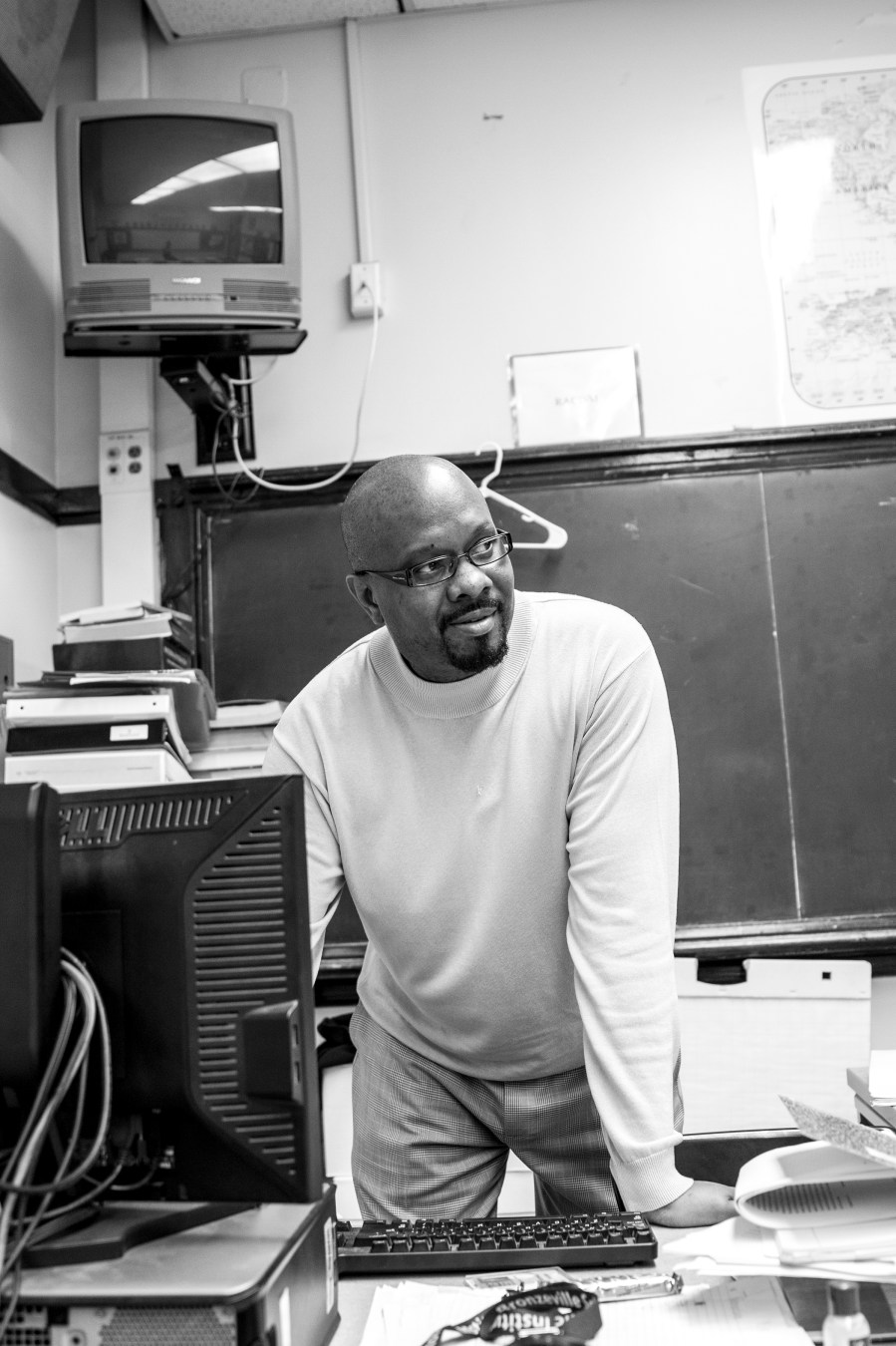

Reginald Grigsby, a history teacher at the Bronzeville Scholastic Institute, one of three schools inside the old Dusable High School building in Bronzeville and not too far from Dyett’s campus, said “there’s a system of apartheid in our public schools” and that the line between schools that have and those that don’t is increasingly stark. The much whiter schools on the north side of the city fare much better in terms of resource and access than the mostly black and poor schools on the city’s south and west sides, he said, where most of the closings have occurred.

Grigsby was among the teachers laid off earlier in the year, and was one of only a handful of African-American male teachers at his former school. He said more than simply dislodging students and teachers from buildings, the cuts and closings dislodge students and teachers from each other’s lives.

“I think the people sitting in an office Downtown making decisions that affect many of these kids don’t realize that school is their only stability,” Grigsby said. “Once the educator is removed from the equation, nobody’s looking at how the children will be affected, when the one thing that has been stable is removed.”

‘Our school is not preparing us’

The nearest high school, Wendell Phillips Academy, is more than two miles away and is a so-called turnaround school. Because of its history of poor academic performance, the city has appointed a private management company to run the school. Other options on the south side include a school that’s already overcrowded, charter schools or one of the city’s selective enrollment schools.

As a school on the district’s phase-out list, Dyett has found itself in a kind of social and academic limbo. The school is in the second of a planned three-year phase out. It stopped accepting incoming freshman and its budget has been slashed dramatically. Much of its staff has been laid-off. Honors classes have been scrapped. Because of the teacher layoffs, core classroom instruction such as algebra and biology has been replaced with online classes. So have courses like gym and art, as well as the school’s limited number of advanced placement classes.