By Dr. Dave Campbell

I first met Mayor Pete on a recent evening in Manchester, New Hampshire. The thirty-seven-year old Mayor of South Bend, Indiana is a Harvard-educated Rhodes Scholar. He is the first major openly gay candidate for president, as well as the first millennial with a real chance to win. A deeply religious person, we talked life, family, service, policy, his health and the future of health care in America.

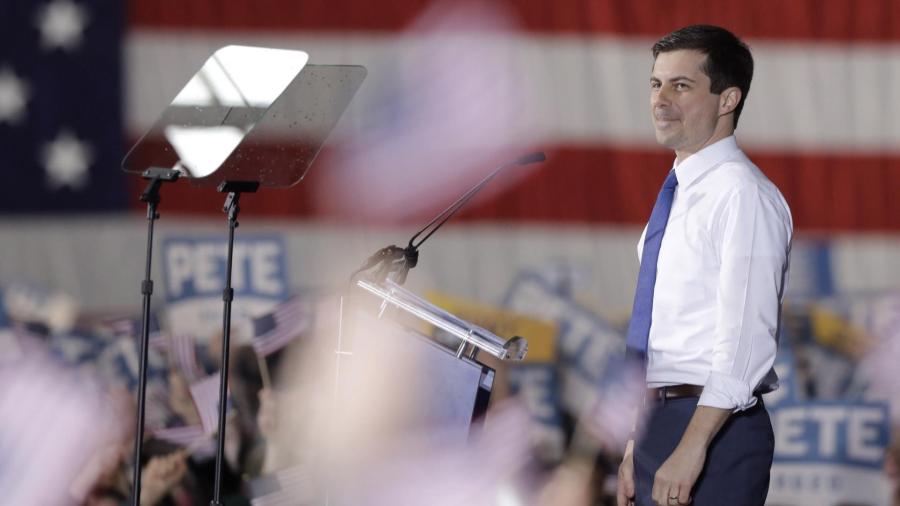

Watch: Dr. Dave Campbell talks with Mayor Pete in Manchester, NH

It is more important than ever that a presidential candidate’s mental and physical health be known to the American people. Each person’s vote for president can be made with more passion and more practical knowledge by investigating the candidate’s health and the health of their family. All of us make decisions based on our experience, education, principles and integrity. In this voting cycle many of the Democratic candidates have already released years of income tax returns. My goal for the American people is to have the candidates be equally transparent in their disclosure of personal health information. The full-release of comprehensive medical records on all candidates, and interpretation by physicians, is vital before voters cast their ballots. It doesn’t need to be like pulling teeth.

Both the age and medical health history of candidates varies widely, spanning three generations and a wide variability in underlying health conditions. Pete Buttigieg is the youngest at thirty-seven and it would be impossible to be healthier, since he has no health problems. Senator Bernie Sanders is oldest at seventy-nine and based on what we know right now is in good health. On the Republican side, incumbent President Donald J. Trump at seventy-two has no major health issues either, according to government doctors.

MAYOR PETE’S PERSONAL HEALTH

By all standards, Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of his hometown of South Bend, Indiana, is young to be running for the presidency, or is he?

If age is measured by years, then sure. He is two generations behind Senator Bernie Sanders and former Vice-President Joe Biden. However, a President Pete Buttigieg will be middle-aged in office if he wins two terms. When I mentioned this to Mayor Pete during our interview on health and healthcare in early April 2019 he was pleasantly caught by surprise.

He said, “Cool. Wow. What counts as middle-aged? That’s interesting.”

“Forty-five,” I responded.

“Alright, alright, there you go,” he quipped.

“So, you’re not as young as everybody says you are,” I said.

Mayor Pete let out a sigh of relief and said, “Good…Good…I guess…No, it’s been interesting, the age thing especially because many of the voters.” He paused as I interrupted.

I saw the puzzled and pained look on his face and felt concern that I had hit a raw nerve, which was not my intent. I said, “That hurt, didn’t it, when I said…”

“A little bit, yeah, thought I was supposed to live forever. But our kind of generational appeal is, seems to be, resonating with young people for sure. But especially with older people. With people my parents age. They seem enthusiastic about the idea of a new generation stepping up and leading. And I think about that a lot in terms of how we build an alliance,” Mayor Pete said.

“Because, of course, politics, at least good politics is a practice of addition and multiplication, and you’re building a coalition, and I’m really excited about the sort of innate support that a lot of older people feel for younger leaders,” he finished.

Just as the last words rolled off his tongue, a huge American flag came into our view from inside the large, black SUV that was transporting us from the classic New England college town of Durham, situated along the Great Bay at the mouth of the Oyster River, back to Manchester, New Hampshire. “Look at the size of that flag. Is it a gas station? Something else? Crazy. Seems out of proportion to me,” he noted.

As we talked about the giant flag, I asked Mayor Pete how somebody’s experiences and frames of reference inform their decision-making, to gain a deeper understanding of his basis for healthcare policy. We discussed the recent death from cancer of his father and how personal things that he has experienced speak to how he will be thinking of other American’s in his decision-making for their health.

Mayor Pete said, “Well one of the things I’ve reflected on and talked about on the trail is, you know, you want your decision-making to be as free as possible from things that shouldn’t matter. And so, as example of that, that I reflect on a lot in the context of healthcare coverage, is that while we were making decisions about supporting dad in his final weeks, as he was losing his struggle with cancer, we were just thinking about the medical side, not the financial side, except for one period where we were looking at long-term care. And you don’t want a family to have to think about that when you’re experiencing, however difficult they are, … moments that can be really-important. You know, some of the best conversations I had with my dad were in some of those struggles. Taking him to the hospital and bouncing around from one experience to another also meant we spent the day together. And there’s a lot to do. There’s a lot of hurry up and wait, just like in the military.”

As Pete Buttigieg, twenty-three years my junior, only two years older than my oldest daughter, I thought about the “hurry up and wait” that is endemic to military service in the United States. I thought of my experience as a surgeon in the United States Army Reserve Medical Corps years ago, in the time of the Gulf War, code-named Operation Desert Shield. My grey hair, Florida sun baked skin, and middle-aged paunch, compared to Pete’s dark hair, Indiana sun-protected smooth skin and weight in the normal range was a sobering reminder of how quickly time passes for all of us. I thought of my own mother, father and younger brother who all died within the last few years and how important Mayor Pete’s time spent with his father before he died was in the further development of Pete Buttigieg’s humanity and his role as the potential leader of the free world.

“And so, you know, some of the conversations I’m really thankful for happened in that context. But it’s because there’s one thing we’re really having to deal with and that was his health, not his finances,” said Mayor Pete. “I’ve seen that over, and over again. I remember a case I was actually, bizarrely found myself on the scene of an overdose situation. I was coming out of an event and there was a kid lying on a lawn, kind of frothing at the mouth and somebody was trying to call 911. And first I assumed the kid was having a seizure, then I was two other kids there too. It was teenagers and that was when I realized this was not a seizure. This was a drug experience. They were probably, it was probably due to the synthetic, so-called synthetic marijuana which is highly toxic. Stuff that a lot of kids get from convenience stores because it’s hard to regulate.”

“I thought he was kind of rolled over on his side and I was propping him against me,” Pete said. He indicated lifting the kid’s chin, “because I thought he was going to choke, and I wasn’t sure if these kids were going to make it. They did. But the one who was in the worst shape, by the time the EMT’s got there he was starting to come out of it, and they brought him back. He was saying, and this was…maybe like a fifteen-year-old, ‘Don’t take me to the hospital. I don’t have any money’. I’m thinking, like how does this kid think, that’s his problem.”

“How did he even think of that as he’s coming out of being nearly comatose?” I asked.

“I guess my point is,” Mayor Pete explained. “You know when our decisions are affected by our range of opportunities and our freedom to make a good decision depends on the constraints we’re under, and part of government’s job, I think, sometimes is to get out of the way. Sometimes it is to get there and tear down obstacles that get in the way of living a good life. Living a life of your choosing and choosing well. Or with being able to do that, so you know every American, every family, every day is making decisions. And we can’t make somebody thrive. That’s up to you. But, we can definitely empower people to thrive, through the services we provide. The kind of framework we create for everybody to live in, the rules we’ve laid down, left and right, boundaries for our life choices.”

He went on, “And the great thing about democracy is we all get to decide together on what those rules ought to be.”

If age is measured in physiological terms, something we physicians often speak of, Mayor Pete is a spring chicken. Throughout the several interviews spread over two days with me, the picture of youthful health. My first impression of the clean-shaven, handsome young man with a tightly cropped and full head of dark hair was that he is physically fit and mentally sound. After just a little conversation, it was obvious he was well-spoken, thoughtful and compassionate. He was kind enough to look past my chattering teeth as we walked through a street and then park in Manchester, where the ambient temperature was balmy for northerners, and those from the mid-west like Mayor Pete, but downright bone-chilling for someone freshly arrived from warm South Florida. They say your blood is thin (whatever that means) if you’re from the Sunshine State. Well, mine was downright as thin as water.

Despite on tour in Afghanistan as an officer in the United States Navy Reserve, deployed while still the Mayor of South Bend, he came back without injury. He fitness was put on display when we shared a workout in the gym of the Holiday Inn Express in Manchester, New Hampshire. As a retired Major in the Army Reserve Medical Corps, I can attest retired Lieutenant Peter Buttigieg’s ability to still pass the Navy Reserve Physical Fitness Requirements. He knocked out a brisk thirty-minute run on the treadmill with a smooth stride. His strong legs were on full display. His effortless running technique spoke to his regular habit of running both on the campaign train and back home in South Bend with his running mates. If I had been his commanding officer, or supervising physician for a military fitness test, I would have had him pound out 54 curl-ups, 44 push-ups, and a 500-yard swim, and that would have been for a male 25-29 years old in the Navy Reserve. But the water in the swimming pool was way too cold to touch, let alone dive into, and there was no curl-up bar, and I didn’t want to try to go push-up for push-up with him, so I let it pass. My judgment as a team doctor for 18 years was that Pete would have completed the requirements with time and energy to spare.

In the carpool karaoke interview from Durham to Manchester (following in the footsteps of trail-blazing work of The Late, Late Show with James Corden), freshly showered and dressed for the day after our work-out, I asked Mayor Pete about his thoughts on how the concept of the buddy system, like used in the military with Battle Buddies, scuba diving, and with friends and family that benefit by mutual support, may benefits health and healthcare in our American society.

“We have seemingly gone away from the buddy system in the United States to the detriment of our health,” I asked. Mayor Pete picked up the conversation.

“I think that’s right, you know, I hadn’t really thought about it in terms of the buddy-system, but I did read a really interesting book, came out recently, called “Palaces for the People.” And it’s partly about cities,” Mayor Pete said. “But it’s really about a subject called ‘social infrastructure’, what the author called it. He started out by looking into this question. There was a horrible heatwave in Chicago in the ‘90’s and as you might expect, lower income neighborhoods tended to have more fatalities. But he dug into the data and what he actually found was that there were two neighborhoods next to each other. Both minority low income neighborhoods. One of them had a lot of fatalities during this heatwave. The other one in terms of its fatality rate was safer than wealthy neighborhoods like Lincoln Park on the Northside. And he went in to say ‘why’ and as he explored what was going on, he found for a number of reasons, many of them accidental, one of the neighborhoods was set up in a way that people knew their neighbors. They checked on each other and there was a really strong social fabric and the other the reverse was the case. And so, people were more isolated. And the larger point is that, when people are checking on each other and looking out for each other, you’re safer. Everything from your survival rate in a tornado to your likelihood to develop different diseases is enhanced if you have people around. We know the social isolation of seniors is a major public health risk.”

Sitting from my vantage in the backseat of the comfortable SUV, camera’s rolling, I felt that I was listening to a future of America that would be appealing to many voters. With just a simple concept of the buddy system under discussion, I had uncorked the flow of knowledge that has become the harbinger of good things to come for the health, healthcare and well-being of those living in the United States.

“There’s a lot of these things we could do something about, some of it’s cultural, some of it I think requires some regard and support for things like family, things that conservatives talk about more, faith communities can do this,” said Mayor Pete. “But it’s also our responsibility, I think just as a, as a country, as a set of communities, there’s some public responsibility to try and create the spaces where these kinds of interactions can happen and foster a culture were that happen.”

If age is measured by wisdom, accomplishment, use of God-given talents, genetics, environmental factors like quality education, and preparation, then Pete Buttigieg is anything but young. He was the president of his high school class in South Bend, the recipient of the JFK Profiles in Courage award in high school for an essay about the Independent Senator from Vermont, Bernie Sanders. After a college degree from Harvard, he went on to receive the highly-competitive and prestigious Rhodes Scholarship. Pete Buttigieg completed post-graduate studies as a Rhodes Scholar at the University of Oxford. He was in good company following in the footsteps of former President of the United States Bill Clinton, and former United States National Security Advisor and United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Susan Rice. Elected mayor at twenty-nine and then commissioned as an officer in the United States Navy Reserve, Pete is anything but young in experience.

The road from historic Durham to Manchester, weaved through the historic heartland of the America I had only read about, as a Floridian. There were many answers to questions in my mind filling the pages of Pete Buttigieg’s book, “Shortest Way Home,” published earlier this year. Thank goodness I had already made the time to read it. It was well worth the time and was effortless, an easy, enjoyable, entertaining read, and contains a wealth of information that brings Pete Buttigieg and his friends and family to life. He describes being in Kabul, Afghanistan, deployed on active duty as a naval officer, encountering a local Afghan proverb which says, “A river is made drop by drop.” This local wisdom made Lieutenant Buttigieg picture the St. Joseph River coursing through his home town of South Bend some seven thousand miles away.

Mayor Pete envisions the United States as a country where the health of the American people can be improved step by step, or drop by drop, incrementally, by harnessing institutions that already exist, improving them, expanding them, to bring safe, quality and compassionate health care to all. Much as he enables optimal health and fitness in himself through attention to nutrition and exercise.

Mayor Pete arrived in the gym to join me at 0700. Sharp. Military precision. While some would still be groggy or grumpy after hundreds and hundreds of handshakes with Manchester citizens, dozens of questions from the gaggle of reporters, after a rousing stump speech to overflow capacity in the Currier Museum of Art, where people were left in the parking lot because of the rush of interested Manchester residents vying for a spot to see and hear Mayor Pete. Not him. He was ‘bright-eyed and bushy-tailed’ as my grandmother Helen used to say. He smiled warmly and greeted me, his staff and the Morning Joe crew with a pleasant demeanor. In the hours I spent with him in New Hampshire, I never saw him lose his temper or get fazed. When addressing the crowd, first outside in a light-drizzle with the temperature just above freezing, and then inside for the lucky three-hundred, with another hundred left outside as the museum couldn’t hold everyone for his stump-speech, while in the car, in the gym, to our walk outside in the street and in the park, Mayor Pete was always engaging and pleasant. At sixty myself, it was tempting to ascribe his vigor and brightness to youth, but it is so much more than that. He has a love for people that comes across in all the interactions I witnessed in those two days.

Mayor Pete says he makes healthy lifestyle choices. I asked him about alcohol and smoking.

“Smoking? You don’t smoke? Alcohol?” I asked.

“Nope,” he said. “Once in a while I’m guilty of a cigar but that’s about it.”

Satisfied, I moved on, knowing that I was barking up the wrong tree if I thought there was some health problem yet to be uncovered in Mayor Pete. There is not, he says.

Quite frankly, at thirty-seven, there weren’t any physical or mental health issues. He father recently died of cancer and his mother survived open-heart surgery. He reports stable vital signs. He seems to be in the sweet-spot of life as relates to health. Not so old to have acquired the inevitable clinical baggage of aging from sagging skin, grey hair, widening gut and a prostate growing like a grapefruit. He hasn’t `reached the day where chronic disease manifests in many. Illnesses that become more common with each passing decade face all of us in some form or fashion. Not yet for the mayor.

I probed for some weakness in his nutritional habits. It was like searching for a needle in a haystack without any needles. He wasn’t sneaking Skittles, scarfing ice cream sandwiches, or secreting M & M’s. Too bad, I could have used a few. I sensed the grueling nutritional pressure for a presidential candidate moving incessantly from event to event, city to town to rural gathering, always with food spread temptingly for the candidate. Pete Buttigieg rarely eats at the campaign events. He relies on Kind bars to keep him going. We laughed about the lessons learned by watching candidates in the past shoveling in food while the cameras were rolling and how unflattering that footage can be. Open mouths, scrambled eggs and cameras are a bad combination for a presidential candidate. However, good fortune was shining on Mayor Pete the morning of our carpool interview. He was able to score an egg-white omelet and brisk cup of coffee at a local diner, absent the TV cameras.

Even with all my best physician-journalist sleuthing, some on camera, and some off, probing Mayor Pete’s current and past medical history was like shaking an apple tree after all the fruit has been picked. Nothing was there. He will rank not just as the youngest presidential candidate for the 2020 presidency, but he will be the standard by which others’ health is measured.

I asked Mayor Pete about his experience with injuries while deployed to a combat zone. I mentioned that my oldest son, Staff Sergeant, Gregory Campbell, United States Marine Corps, has been deployed three times, and seems to have, at least that which he has admitted to me, of the singular injury of developing his first and only cavity in a tooth, which he ascribes to dip and chewing gum to stay alert while on watch.

I told him my son’s story and asked Mayor Pete, “No cavities while overseas?”

“No, no cavities,” Mayor Pete said as he smiled ear to ear with his pearly whites on full display. “I had to see the doc once about something that happened to my eyes. I think because of some sand in the air when I was in Herat, on the Iranian border. But, no thankfully, on my way out I got some excellent dental care that made sure I was ready to be deployed. It was my civilian dentist that was going to do the whole crown thing and I mentioned it during a pre-deployment workup and the doc said, ‘well, you know I could probably take care of that. And the conservative thing would jut be to do blah, blah, blah…’ I didn’t really understand what he was saying and said, ‘well, do you think we could arrange that?’ and he said, ‘yeah, lean back’.

“An hour later, I’m holding on to my jaw and it was fixed,” Mayor Pete said with a grin.

Sand is the enemy for service-members deployed to the Middle East. It not only gets into the eyes, but also weapons, food, and sensitive parts of the body not designed to accommodate grit.

“We were talking about Lasik surgery, Afghanistan and the sand?” I asked.

“I remember that was a thing,” Mayor Pete said. “I just stick with contacts.”

“How about mental health? How do you stay healthy on the trail? You’ve got a tough schedule,” I asked Mayor Pete while we were just getting to know each other, walking through a wide-open park in Manchester.