Too Much Money

The most dangerous thing is illusion. —Ralph Waldo Emerson

It was late summer 2001. I was 63 years old and on top of the world; and I very much liked the view. It felt like the zenith of my life as a man of business and investment, as a husband and father who had lived his life exceedingly well. And yet, I was convinced that there was more successes ahead for me.

I wasn’t interested in taking it easy any time soon.

I had recently retired from Alliance Capital where I began as its chairman of the international division in 1993. That post, in the heady and rarefied universe of global finance, came after rising through the upper ranks of its parent company, Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States, the third largest life insurance company in America and its wholly owned investment subsidiary, Equitable Capital Management Corporation. I was also thrilled to be launching the Africa Millennium Fund, my own operation. With it, I was seeking to realize my life’s dream of creating a Western-style investment fund to drive much needed capital to a continent practically starving for development capital.

After all, I had created investment funds to invest in India, South Africa, and Egypt while at Alliance, so I was confident that I could accomplish this most ambitious continent-wide achievement.

Africa was important to me. Africa is me. I am Africa. I am an African man. That is one of the things that defines Frank Savage. Everyone will tell you that. I’m a lover of Africa. One way or the other, that’s where we all come from; that’s where humanity began. In terms of my heart and my soul, I have been in Africa since I was a kid. My mother planted that seed of the international deep within my imagination long, long ago. It never stopped growing.

In that late summer in 2001, I was serving on several prestigious boards overseeing major corporations and institutions of higher education. I believed, and still do, that part of the obligation of business leaders, men and women who have amassed a lifetime of skills, insights, and influential relationships, should share all what and who they know by sitting on the boards of various corporations and institutions. I must admit that I took pride in this, especially being, for instance, an active member of the board of trustees at Johns Hopkins University and the chairman of the board of trustees at Howard University, institutions that had helped to prepare me for my career.

I cannot tell you how pleased I was to be able to pledge $5 million to Howard; and at Johns Hopkins I set up one of the largest scholarships of its kind for African-American and African students in need of financial assistance to attend that university’s premiere Nitze School of Advanced International Studies. My career in international finance owes a great debt to that school. And through the Frank and Lolita Savage Boost Fellowship, 50 other well-deserving students of color have gotten the same chance I did when I attended this incredible institution in the 1960s.

During that late summer, I sat on the boards of Lockheed Martin, Qualcomm, and Bloomberg LLC. I was also a member of the board of directors of Enron Corporation in what I had imagined would be a sort of crowning glory on an outstanding and fulfilling career.

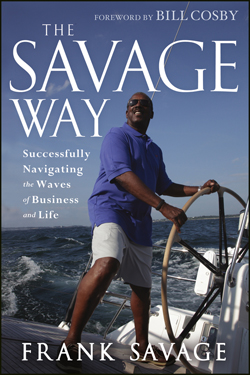

These were good times. Or so I thought. I had experienced half a century of unrelenting success. And believe me, I never for one moment took that for granted. I remember cruising in Martha’s Vineyard during the summer of 2001. It was so beautiful. I was below deck in my custom-crafted, air-conditioned skipper’s cabin. I just sat there and took it all in. Jesus Christ, I thought, I’m so lucky.

I was making a lot of money. I was very successful in business, very successful when I was at Equitable where my job was to bring in what this multibillion-dollar concern did not have—international clients. I was able to attract more than $3 billion to Equitable Capital, which was unheard of. My early success there also marked the first time I was paid $1 million in a single year. And that was just a bonus. I went on to have tremendous success, tremendous. I could do whatever I wanted.

But one of the faults of that period was that people like me had so much success; we had too much money. We used it to buy things. I never thought that I would get into a period where I would ever have to ask questions like, should I buy this or should I buy that? Should I want to? For so long, I could always get whatever I wanted. And I had amassed enough wealth to guarantee a comfortable retirement, although actually retiring never really dawned on me.

Personally, life with my wife, Lolita, could not have been better. We always supported each other. I had my global financial work; she had her international career as a fine painter; together, we had our family, our lovely homes in Italy and another overlooking New York’s Central Park. My family was proud of me, too. Many of my six children had settled into families of their own. Every year I made time to steal away with them and their children to the Vineyard when autumn and summer begin to blend like cool cream in hot coffee.

Lolita and I traveled the world on Alliance business. We’d fly off to South Africa, for instance; we jetted throughout Europe and Asia, all over. We attended some of the most prestigious business conferences in the world, like Davos in Switzerland, World Bank and the Institute of International Finance. It was a deeply enriching experience for us. And it certainly didn’t hurt that Lolita is fluent in six languages and remarkably comfortable in the dizzying whirl of high finance in high places. There were times during these trips in which I happily felt much the way a young President John F. Kennedy said he felt when he was the man “who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.”