Today’s female sports journalists, like most women in male-dominated fields, still have to fight against stereotypes and sexism. But for the earliest women sportswriters trying to do their jobs 40-plus years ago, even getting into the locker rooms to conduct interviews was a major hurdle—one that required persistence, grit and in one case even a federal lawsuit to clear.

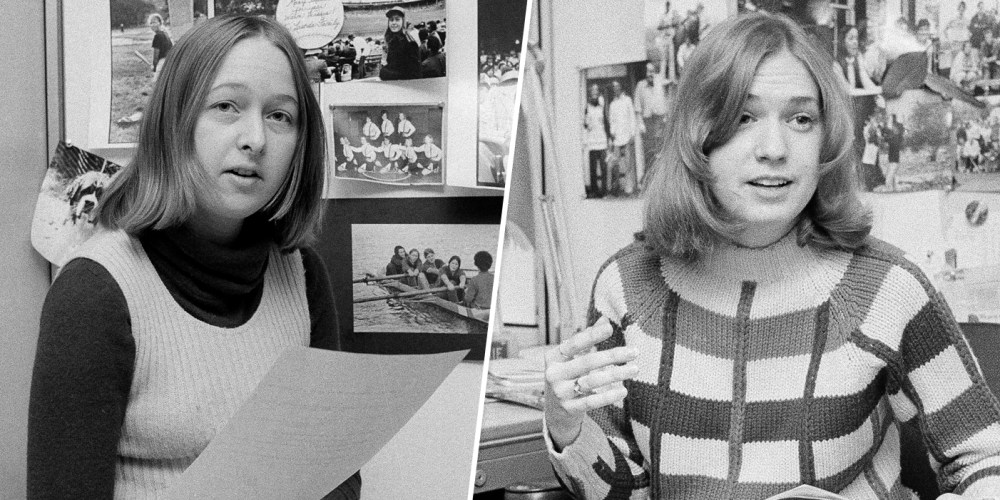

Know Your Value recently interviewed three women sports journalists who battled for access, equality and fair treatment in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Melissa Ludtke: The history-making plaintiff vs. Major League Baseball

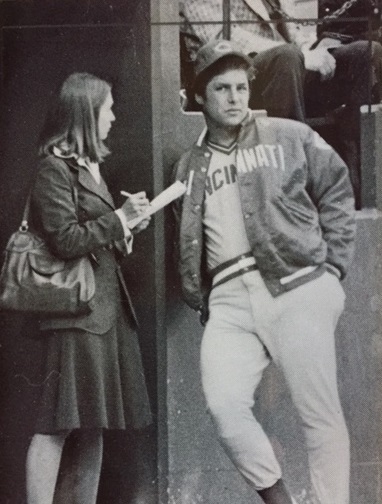

In 1977, the Commissioner of Major League Baseball stopped Melissa Ludtke from walking into the locker rooms, and her fight against him ultimately changed that journey for every woman after her.

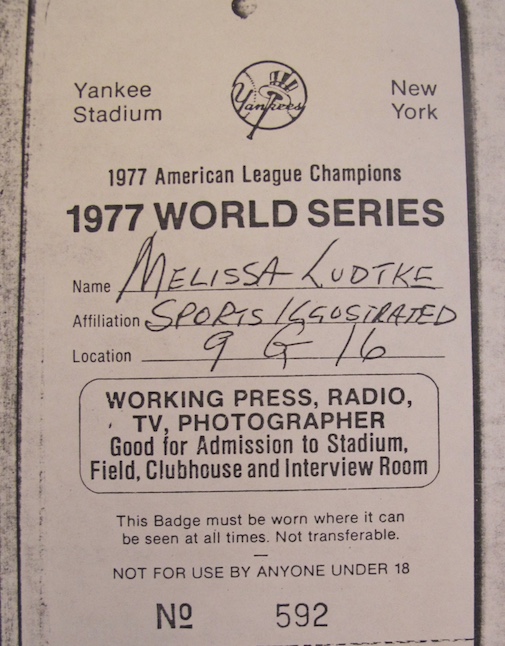

She had been working at Sports Illustrated as a baseball writer — the only woman in the country covering baseball full time, she said. Ludktke had been on the beat for two years when the 1977 World Series took place, with the New York Yankees taking on the Los Angeles Dodgers.

She had already made inroads with the Yankees, using her New York location and a low-key approach to work her way into the locker room. “I never made a public request or banged on the door,” Ludtke said.

“I’d been hanging out for 18 months trying to get into the locker room. I worked with Mickey Morabito, the Yankees’ PR person, who was my age and kind of got it,” she added. “He had the idea to open up a side passageway through to get me into Billy Martin’s office, which is separate from the locker room, and I’d done that for the whole back half of the 1977 season.”

Morabito had also given her a formal locker-room pass a few games earlier, so Ludtke didn’t expect any problems at the World Series. She had press credentials, and she knew the Yankees would have no issue with her in the locker room.

But she wanted to interview the Dodgers, too, and as a courtesy she approached manager Tommy Lasorda, who passed her to players’ rep Tommy John—who, in turn, asked players if they were OK with a woman in the locker room. The majority said ‘yes,’ John told Ludtke, so it was fine by the team. But he also asked her to give Steve Brenner, who handled public relations, a heads up.

“I told Brenner and he looked absolutely ghostly,” Ludtke said. “He said nothing and walked away. I enjoyed dinner with other reporters, and then I heard my name over the loudspeaker asking me to come to the press box.”

Her old pal Morabito was there, with a message from Major League Baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn: She was formally banned from the locker rooms. It didn’t matter if the Yankees or the Dodgers or whomever had granted permission; Kuhn had not, and his decision was final. Kuhn would not speak to Ludtke, despite her requests.

The next few weeks were a whirlwind. The commissioner met with Ludtke’s editor. They suggested she get a male “escort” who would deliver the players to her outside the locker room after Game 6, an effort that failed miserably as she knew it would.

Finally, in November, Sports Illustrated asked Ludtke if she would be willing to be a plaintiff in a lawsuit against Major League Baseball arguing for women’s access to the locker rooms.

Ludtke, then 26, agreed. A month later, when Time Inc. filed Ludtke v. Kuhn in late December, the media frenzy began: Male columnists weighed in and took potshots, implying Ludtke and other women simply wanted to ogle the athletes. “Saturday Night Live” lampooned the concept, with a lewd Laraine Newman cornering O.J. Simpson in a locker room. During a play at Christmastime, Ludtke and her parents even overheard the people behind her debating the merits of her case.

“It was a wakeup moment for me that I had made a life-changing decision,” Ludtke said. “It was turning into a symbol of women’s lib, and that was something I just had to accept and steel myself for.”

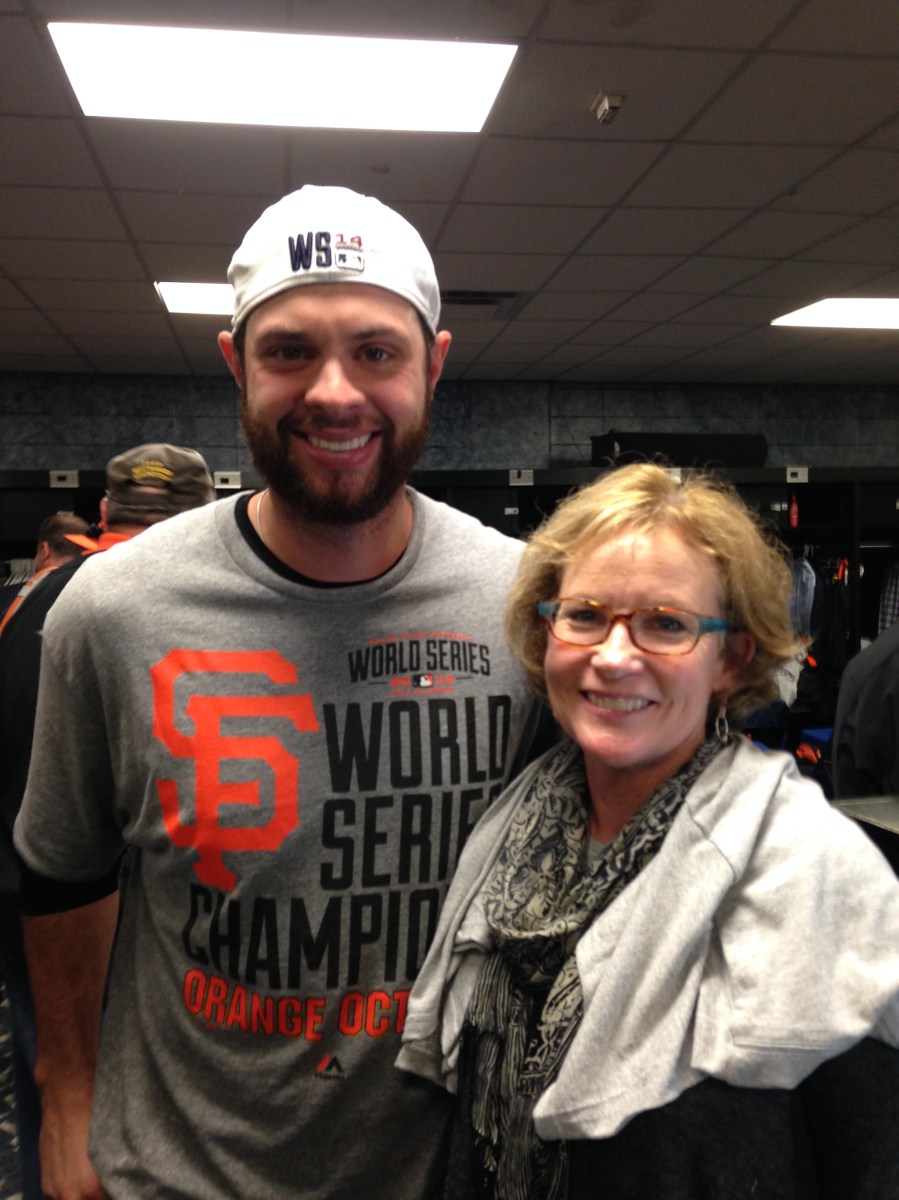

Ludtke v. Kuhn carried on for most of 1978, with lawyers representing Sports Illustrated arguing the MLB’s ban violated Ludtke’s Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process and equal protection. U.S. District Court Judge Constance Baker Motley—herself a barrier-breaker as the first African-American woman named a federal judge—ruled in favor of Ludtke and Time Inc. that September.

“I was happy, of course, but I wasn’t surprised; I felt the lawyers had made the case beautifully,” Ludtke said. “Toronto was playing the Yankees that night. And I immediately decided I wasn’t going to the stadium.”

Ludtke knew, and knows, that might sound counter intuitive. But she also knew a lot of women would flock to the locker room that night, sent by editors who wanted to make a point and get a headline.

“But that wasn’t why I filed the suit,” Ludtke said. “The point was to be there when there were no cameras. I just wanted to do my job.”

Stephanie Salter: I was kicked out of the Baseball Writers Association Dinner

“I kind of backed into sports, like a lot of things in my life,” said Stephanie Salter, who worked at Sports Illustrated in the ‘70s. She grew up in Indiana, where Hoosier culture meant everyone had some interest in basketball and football, at least.

But she never planned to get into sports journalism; she simply liked the writing of a columnist, Kent Hannon, at Purdue’s daily newspaper during her college years. She marched into the paper’s offices and signed up as the only woman on the sports team.

“I was assigned to do a color piece at a football game in 1968, and they wouldn’t allow me in the press box because the language was too tough for ‘a female,’” Salter said. “And yet they were fine having women from [auxiliary organization] Angel Flight bring these male writers drinks and food.”

Unfortunately, Salter said, “it was just the first of stupid, insulting contradictions throughout my career in sports.”

Salter ended up following Hannon, who had become a mentor, to Sports Illustrated in New York City. Overall, the magazine was “still a pretty sexist place” when she joined as a fact-checker in 1971, but a few iconic writers like Dan Jenkins were supportive and helped her to “learn by osmosis how to write.”

Then, one Sunday night in 1973, a colleague swung by the publication’s office with tickets to the Baseball Writers Association dinner. The association had comped the tickets, as SI journalists weren’t daily writers as required for membership, and Salter asked to take one.

“Someone said, ‘Oh, it’s for men, they won’t let you,’” Salter recalled. “I said, ‘They won’t do that! It’s 1973!’ Well…ha.”

Salter donned a black halter dress and headed to the black-tie event with a few colleagues, not knowing she was about to make headlines.

“I got through the National Anthem and the fruit cup—about 10 minutes—when they sent over Jack Lang, the [executive secretary of the Baseball Writers Association],” Salter said. “I told him I had a ticket, and he started shoving money at me, telling me that if I didn’t leave he’d get security.”

Salter stood her ground, but by the time a “bent old security guard came up to me I decided it wasn’t worth it. Three of the guys at the table left with me.”

Others noticed the scene, and someone called The New York Times which, among other outlets, covered the incident in a short piece. SI’s managing editor was supportive, and he and Salter planned to sue, but the company’s legal team advised that because SI writers weren’t eligible to be members of the association the case likely wouldn’t proceed.

Ironically, Salter later became a member of the Baseball Writers Association when she joined the San Francisco Examiner (now the Chronicle) as a sportswriter in 1976. There she “covered everything but football,” including the Oakland A’s baseball team and the Golden State Warriors, the basketball team with whom she traveled.

Salter loved traveling with the Warriors, who at the time were an all-black team and coaching staff, save one white player. “What I dealt with isn’t the same as racism, but they’d say to me, ‘We get it—you look different from everyone else. We know what that’s like.’”